In the battery and solar industries alone, the EU Commission estimates that 800,000 and one million skilled workers will be needed by 2025 and 2030 respectively.

These figures show that the greening of the EU economy has huge potential to create new jobs and transform the existing labour market — but they do not show that the EU green deal could also add to existing social and gender inequalities.

“If we don’t take an active policy towards making sure that these jobs and these skills are accessible to both women and men and address some of the obstacles, then we’re going to recreate the same sort of imbalance on the labour market in that new field,” Blandine Mollard, a researcher at the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) told EUobserver.

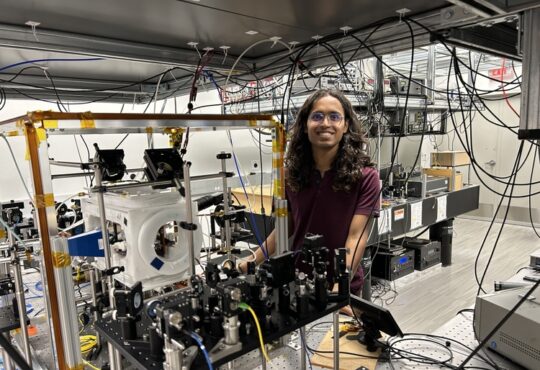

An OECD analysis shows that women are already under-represented in green jobs, with only 28 percent of all green positions in 2021 being held by women.

“This disparity means that women are missing out on new green opportunities as well as a chance to close the earnings gap,” write OECD policy analysts Ada Zakrzewska and Lana Fitzgerald, as these roles tend to pay up to 20 percent more than others.

“What we have to fundamentally avoid in the green transition is that we create the gender pay gap in emerging sectors,” Judith Kirton-Darling, acting joint general secretary of IndustriAll Europe, told EUobserver.

But so far, the links between gender equality and the policy areas of the European Green Deal have not been made in a very “comprehensive” way, EIGE’s analysis reveals, which risks widening gender inequalities or, at best, simply perpetuating them.

This is because public policies are never truly gender-neutral, explains Mollard, who stresses that not mainstreaming gender in these policies and funding programmes is “a bit of a missed opportunity”.

For example, the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan mentions that there is “a clear opportunity for harnessing female talent”, but provides no guidance on how to better integrate women in these sectors.

“We can’t think about this [green and digital] transition by only looking at half the population,” Kirton-Darling said.

For the trade unionist, the EU lacks a more progressive agenda on diversity, attractiveness of industries, good quality jobs and a framework for women to enter, stay and progress in the industrial sector — including in engineering leadership positions.

“We won’t be able to fill the labour shortages in our sectors with just middle-aged white men,” Kirton-Darling added.

20 million women to achieve parity

To achieve parity in OECD countries, the organisation estimates that at least 20 million women would need to move into green jobs. But how could this goal be met?

First, with some policy coherence, EIGE’s researcher says.

“The starting point is that we have already very few women in those sectors,” Mollard pointed out. “What we need is a very ambitious upskilling and reskilling strategy”.

In the EU’s transport sector, for example, only 22 percent of workers are women, while in the formal care sector, they account for 90 percent of the workforce.

Gender segregation is one of the reasons, i.e. the fact that women and men tend to study different topics that are often aligned with gender norms and roles.

The burden of unpaid care responsibilities, insufficient work-life balance or insecure working conditions for some positions, such as the ones in the transport sector, are other factors.

“We find that access to care services is really essential,” Mollard said, highlighting the fact that women spend twice as much time in unpaid caregiving than men.

Another effective tool to make it easier for women to enter these jobs is conditionality in the allocation of EU funds, Katharina Wiese, policy manager at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), told EUobserver.

“We have to condition that a certain amount has to contribute to digitalisation or the green transition, and you can add a gender equality aspect to that,” she said.

For example, EIGE analysed the use of the Resilience and Recovery Fund by member states, which was successful in terms of mainstreaming climate goals, with at least 37 percent of the fund earmarked for the green transition.

“Unfortunately, we have not seen such a level of commitment to gender equality,” EIGE researcher regretted.

And just because a job is created, it is not necessarily a decent job, Wiese argues.

In her view, decent jobs are also those that allow women to enter the labour market, especially if they also have care responsibilities.

“But often, if it’s not even mentioned [the gender dimension], then policies don’t really respond to it,” the EEB policy manager concluded.