Ex-Nigerian official defrauded American taxpayers by stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars in coronavirus relief benefits

It was May 2021. A year earlier, Rufai had pulled off a spectacular heist of U.S. taxpayer money. The calm with which he moved through the airport belied the chaos he had left in his wake.

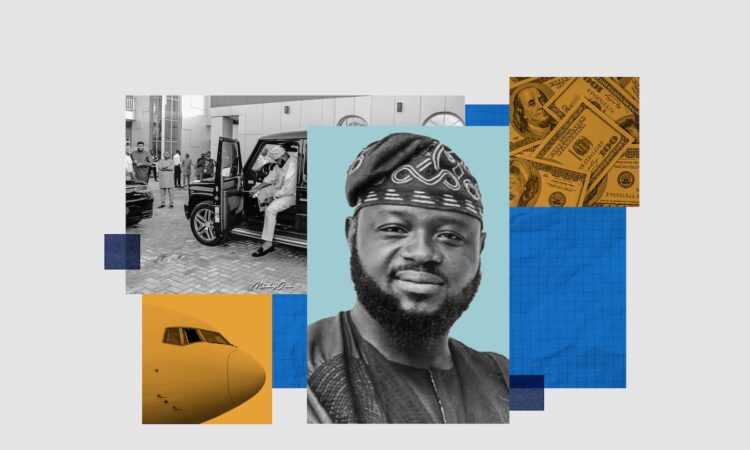

His brazen and repeated pilfering of coronavirus relief funds had helped freeze the entire unemployment system in the state of Washington, where he had obtained identifying information for unsuspecting residents. For months, state and federal officials struggled to get ahead of Rufai and other fraudsters, sparking investigations on two continents that culminated in a guilty plea. Eventually, they would discover in Rufai’s email accounts and phone the personal data of 20,000 Americans and voluminous stolen tax returns, as well as photos of Rufai with a powerful Nigerian governor and images of him dressed impeccably in dark sunglasses and royal-blue robes. In one, he sat on an ornate thronelike chair.

Rufai had managed to escape the United States for relative safety in Nigeria in late 2020, just months after his heist. Remarkably, he later returned. Now, as he approached the ticket agent, six law enforcement officers were positioned nearby, watching him.

Since the coronavirus pandemic hit in early 2020, the U.S. government has spent more than $5 trillion to respond to the crisis and stabilize the American economy. Much of that money helped families and businesses survive a dire economic shutdown. But billions of dollars were stolen, and no one is sure, even now, exactly how much has disappeared.

Some of it was nabbed by U.S. criminals, but a chunk went to foreign nationals who had honed their tactics in defrauding people through identity theft and scams over years and saw in the pandemic a chance to hit it big. Rufai’s wild tactics and dramatic life story — laid out in vivid detail in court documents — offers a startling view of one of the many accused scam artists who siphoned riches from the huge money pot created by Washington in 2020 and 2021.

This article is based on interviews with nearly 20 people in the United States and Nigeria, including state and federal officials. It is also based on a review of government records in both countries, including letters from Rufai and his friends and family members, details of bank account transfers, and transcripts of his jailhouse calls. Through his lawyer, Rufai declined to be interviewed. His lawyer also declined to answer questions about the case.

The details paint a portrait of how a seasoned identity thief hit the jackpot when covid funds began to flow, preying on a tremendous amount of money that was suddenly thrust into the economy in a way that made it very easy to steal. His previous efforts at defrauding the U.S. government amounted to less than $100,000 over three years, according to federal prosecutors. But in a span of six months in 2020, he was able to swipe more than half a million dollars, prosecutors said. He was one of the most prolific thieves but joined hundreds of others, both international and domestic, who overwhelmed government officials trying to protect billions of dollars.

Rufai emerged from a difficult and abusive childhood and rose to the upper echelons of Nigerian politics, where by his own telling he imbibed a culture of corruption. He adopted the tactics of Nigerian scam rings and honed his fraud skills in the years leading up to the pandemic, all the while burdened with a lingering gambling addiction. And once he committed his most dramatic theft of U.S. taxpayer funds, he indulged in a lavish and splashy lifestyle.

“Every time I reflect back to my actions, I feel so ashamed and so disgusted,” he said at his sentencing hearing on Sept. 26, according to a court transcript. “Why did I even get myself into this in the first place?”

A scheme pays off

Rufai was born in Ogun State, in Nigeria’s southwest. His father ran a large poultry farm and had five wives and 13 children, according to a memorandum submitted to the court by Rufai’s lawyer that sought leniency in sentencing. Rufai’s mother abandoned the family when he was a baby, and his upbringing was a harsh one, with little affection and regular beatings and yelling. When he was a teenager, his father beat him in the head with a cane and fractured his skull as punishment for leaving the house without permission, according to the memorandum.

Rufai initially struggled to gain admission to university but eventually attended college and graduate school, borrowing money from family and friends and working menial jobs to make it through. At university, his focus was diverted by a gambling addiction, which began with playing dice with friends and escalated into visiting casinos.

“The gambling got into me,” Rufai’s sentencing memorandum quotes him as saying. “If you gamble, you want money all the time.”

After finishing his university studies, he struggled to find work, which he attributed to a system of nepotism in Nigeria. He married in 2014 and found it challenging to fulfill his many obligations.

“After I got married all my burdens increased because I had to take care of my wife, my younger siblings and my sick mother that all depended on me,” Rufai wrote to the judge in his case.

By 2017, Rufai was supplementing his business endeavors through theft from U.S. government programs, according to prosecutors. It is unclear how or why he entered this world, but his tradecraft, as revealed in documents filed in U.S. federal court, drew from tactics used frequently by Nigerian criminal rings.

Rufai traveled to the United States regularly, visiting three times between 2017 and 2021 and staying for months at a time. Between 2017 and 2020, he submitted 675 fraudulent claims to the Internal Revenue Service for tax refunds, using the stolen data of real Americans, according to a plea agreement he signed in May. The claims were worth more than $1.7 million, though he only received around $91,000.

He also targeted disaster victims. In August and September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Harvey devastated parts of Florida, Louisiana and Texas. Rufai used the stolen personal information of 49 Americans to request hurricane relief benefits, according to his plea agreement. Thirteen of these claims were paid out, totaling $6,500.

At Rufai’s September sentencing hearing, his attorney, Lance Hester, attributed one motivation behind the fraud to his client’s gambling addiction.

“He learns of this scheme, he is introduced to it, he tries his hand at it, and much like gambling, a slot machine or rolling dice with others, occasionally the scheme pays off,” Hester told the judge, according to a transcript. “And just when it seems over, he gets a payoff. And meanwhile he is desensitized. But he just does it.”

As he was launching his forays into fraud, Rufai was also entering the world of Nigerian politics, motivated, he would later say, by the country’s endemic corruption. In 2018, he challenged an incumbent and ran for a seat on Nigeria’s house of representatives as a member of the All Progressives Congress party, or APC.

“Ready and Committed to serve with Trust and Ethics,” one of Rufai’s campaign posters read; “The choices we make are ultimately our responsibility,” read another. Later, when recounting his life story in court documents, Rufai had a cynical take on Nigerian politics, stating in his sentencing memorandum that winning requires the buying of votes.

“Almost everything in Nigeria is corrupt,” he was quoted as saying, with his lawyers attributing his actions at least in part to a culture of corruption that had been all he knew since he was a child. Rufai lost the vote in the February 2019 election and “wasted a lot of money” on the campaign, his lawyers later wrote.

After his loss, he applied for a visa to the United States, and arrived in February 2020, just as the coronavirus was rapidly spreading throughout the country. He told the U.S. government that he would stay with his brother in Queens. The New York borough would soon become an epicenter of the U.S. coronavirus pandemic. Hospitals near his brother’s home were overwhelmed with sick and dying patients.

By late March, the federal government had passed the Cares Act, a $2.2 trillion aid package that included more generous unemployment benefits. To get the money out fast in a dire time, the federal government allowed some applicants for the program to “self-certify” their eligibility without providing proof, a feature that auditors said raised the risk of fraud. Stealing these funds from one person wouldn’t be much of a heist. But stealing this money from a lot of people would lead to a big payday.

In the United States, as help started flowing from the federal government, Washington state’s unemployment office almost immediately began getting calls from residents wondering when their enhanced unemployment checks would arrive, said Suzi LeVine, the former employment security commissioner for the state. Washington had one of the country’s first known coronavirus cases, and by March 28, the state was receiving 28 times more unemployment claims than it had just three weeks prior.

“We’re facing this unbelievable amount of pressure,” LeVine said. She and her colleagues slept little and worked constantly during those weeks and months.

Washington had a modernized unemployment insurance system compared with other states and relatively high base unemployment benefits, and it was able to integrate the extra federal benefits into its regular state payments by April 18, sooner than many other states. But that success was part of its undoing, making it a lucrative early target for fraudsters.

“Because we were at the tip of the spear, we were attacked first,” LeVine said.

Over the course of a single week in late April and early May, Rufai created several Washington state unemployment accounts, according to court records. In his email account, Rufai was storing the private data of more than 20,000 Americans, investigators later wrote in court documents, giving him ample information with which to submit fraudulent claims.

In the same time period, his bank account in Nigeria received the equivalent of approximately $10,000 in deposits, according to Nigerian law enforcement records obtained by The Washington Post.

Simultaneously, he was building his profile locally. A local magazine published stories on Rufai’s donations of food packages to the needy and party faithful, describing the latter as a “stimulus payment.”

In all, a Citibank account in Rufai’s name received over $288,000 in deposits and $237,000 in withdrawals between March and August 2020, U.S. investigators found. Rufai’s Nigerian accounts received deposits between mid-March and mid-May totaling at least $75,000, according to an affidavit by an investigator with Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, which was filed in Nigerian court and obtained by The Post. The affidavit notes that before mid-March, the account had rarely received “such traffic and huge inflows.”

To evade detection by Washington state, Rufai used a simple but incredibly effective method to mask his Gmail address as a way to avoid tripping fraud alerts. Rufai inserted periods into different parts of his email address, sandytangy58@gmail.com, to file multiple applications.

In the same week that Rufai was opening his unemployment accounts and donating food to party supporters, LeVine said she began receiving messages from people she knew who said their companies had received unemployment claims for them even though they were still working. They asked what on earth was happening. Federal investigators had also noted the spiking fraud risks.

“By early May, late April was when we were starting to realize this was a huge deal,” said Seth Wilkinson, an assistant U.S. Attorney in Seattle.

Indeed, Rufai was one part of a massive wave of cyber fraud that had launched within days after the extra federal benefits became available. In an alert to states, the U.S. Secret Service said people outside of Washington were receiving multiple bank deposits from the state’s unemployment benefits program, all in the names of different people with no link to the account holder. Rufai obtained his data on Americans through “unlawful means,” according to his plea agreement, including by misusing an IRS tool meant to help students apply for financial aid. Auditors and cyber crime experts in general also pointed to massive data breaches in recent years that have left millions of Americans’ information exposed and vulnerable to abuse.

In all, state auditors estimated thieves stole $647 million from Washington’s pandemic unemployment benefits, with $402 million recovered as of October, said a spokeswoman for the Washington Employment Security Department.

Around 9 p.m. on May 12, LeVine was riding her stationary bike at home when she received a text from a colleague in state government who had received a letter from the unemployment agency asking for more information on a claim made in the person’s name. One problem: The person was still employed by Washington state.

LeVine searched through the internal unemployment claims system and found several other colleagues, still employed, who had supposedly made claims.

“It was like watching the taillights of the getaway car,” she said.

LeVine and her colleagues felt they had to take drastic action to have a chance of reining in the theft. The next day, on May 13, they shut off the entire system, halting payments to more than a million people — including many legitimately unemployed Washingtonians struggling to survive during the pandemic.

“It was a sledge hammer, not a surgical tool, and it was an awful thing to have to do,” she said.

The halt, which lasted three days, gave analysts time to understand the commonalities between suspected fraudulent claims.

But the shutdown and ongoing efforts to fight fraud had a cost, too: More employees were assigned to fraud prevention, delaying payments to the needy, especially those with more complicated employment histories. And some characteristics of the fraudulent claims — using nontraditional financial services to receive funds, receiving money in accounts under different names than the unemployment claim — are also common among people without access to banks, tribal or other communities who share bank accounts or immigrants.

And the state anti-fraud efforts did not immediately stop Rufai, according to court documents. On May 18, someone using Rufai’s email address submitted a claim to Washington state and directed that it be paid out to a woman in Richland, Mo. The next day, her account received nearly $10,000 from Washington state, as well as another $9,000 from the Maine Department of Labor. The woman later said she withdrew $11,000 of the funds and sent the money to an address in Queens — Rufai’s brother’s apartment. The government believes the woman, who is elderly, was an unwitting “money mule” used by Rufai to transfer funds.

Prosecutors believe Rufai had been one of the more prolific scammers, at least in the early days of the pandemic. His email account “was among the accounts that filed the most suspected fraudulent claims in Washington state,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Cindy Chang, who along with Wilkinson prosecuted Rufai.

Soon federal investigators were on to him. Washington state had handed investigators a database of email accounts used to submit claims during the period of heavy fraud. Rufai’s email address had been used to make 102 claims that were worth more than $350,000 in Washington state, the database showed. Ultimately, prosecutors alleged in court documents that Rufai had submitted at least 224 fraudulent unemployment claims to nine states, netting a total of $497,000, as well as 19 fraudulent loan applications for pandemic-related federal programs for businesses, through which he received one $10,000 grant.

On June 19, 2020, investigators asked Google for information on the account and learned that a phone number associated with the account had been provided on Rufai’s 2019 U.S. visa application, according to an FBI affidavit filed in court.

Still, Rufai remained free and began buying expensive luxury goods. In July, he purchased a Mercedes-Benz G63 SUV from a New Jersey dealership for $71,620, paying with a combination of checks and cash. Such luxury vehicle purchases are a common method of laundering funds, Chang said.

Investigators were compiling evidence, but the case was incredibly complicated, involving multiple states and a raft of crimes. Rufai was able to leave the United States for Nigeria on Aug. 9, 2020. His newly purchased Mercedes would arrive there several weeks later, according to court documents.

The federal agents investigating Rufai were triaging large amounts of information as they looked into dozens of targets simultaneously, Chang said.

“The gathering of the initial data about fraudulent claims was a huge undertaking,” she said.

FBI Special Agent Andrea DeSanto, one of the main investigators on the case, said the Rufai investigation was “complex and multifaceted.”

“We were still working to attribute the claims data to him as an individual at that time,” she said.

Four days after leaving the United States, Rufai was named a senior special assistant to Dapo Abiodun, the governor of Ogun State. He was paid $2,000 as his official salary, but also received $50,000 for “introducing people to the governor,” his lawyers later told the federal court. It was much higher than the average Nigerian’s salary.

Political observers and cybercrime experts in Nigeria noted the timing of Rufai’s ascent to power — just after he had committed his most successful fraud yet in the United States.

“These guys go into fraud, and they use it to go into politics,” said Udim “Manny” Manasseh, who runs FutureLabs, a tech hub that trains Nigerians to use their skills for legitimate business rather than crime.

On Rufai’s phone, investigators later found pictures of him in what appeared to be the November 2020 edition of a magazine called Gateway Times Nigeria. In the photos, Rufai was dressed in deep-blue robes and dark sunglasses and identified as a “property merchant.” Publisher Dayo Rufai told The Post in WhatsApp messages that he is close friends with Abidemi Rufai but is unrelated to him. Dayo Rufai declined to say whether Gateway Times Nigeria ever published the cover issue featuring Abidemi Rufai.

“Never Mock People in Their Trying Times,” the magazine cover quotes Rufai as saying. Other pictures investigators found showed Rufai in the driver’s seat of the Mercedes SUV he had purchased in the midst of his covid relief fraud.

A scramble, then an arrest

In January 2021, investigators asked Google for the contents of the sandytangy58@gmail.com account and its associated Google Drive account. When Google provided the information in February, investigators were astonished.

The account contained over 1,000 emails from the Washington state unemployment agency, personal data for more than 20,000 Americans and “a very large volume” of Americans’ real personal tax returns. They also found evidence that Rufai had targeted U.S. businesses and that his frauds on the American government stretched back to at least 2017.

In a major misstep, Rufai also had stored photos of himself on the account.

The haul was “pretty shocking,” said FBI Special Agent Heidi Hawkins, one of the lead agents investigating Rufai. Investigators could now pinpoint him with some certainty as the perpetrator of the fraud.

As long as Rufai was overseas, however, he would be difficult to bring into custody. Nigeria has an extradition treaty with the United States, but such requests require far more work and coordination between U.S. government agencies than a typical prosecution, experts said. Rufai’s status as a serving government official affiliated with the ruling party would probably make the matter even more complicated.

Then came breakthrough in May 2021. Federal agents had requested Rufai’s travel records and found to their surprise that he had flown back to the United States in March. They also discovered that he was due to get on an outbound flight on May 14.

They had just two days, or he’d be gone again, perhaps for good.

“I felt a bit of satisfaction knowing that we could possibly bring someone to justice who’s been defrauding the American government,” Hawkins said.

To make that happen, DeSanto, Hawkins, their Justice Department colleagues in Seattle and fellow agents in New York had to scramble, compressing investigative and legal steps that would normally take weeks into the span of 48 hours. On May 13, DeSanto and Hawkins flew from Seattle to New York, spending most of the flight preparing a complaint detailing evidence against Rufai. On May 14, they spent the day with their New York colleagues preparing for the arrest.

Around 7:45 p.m., Rufai approached the Royal Dutch Airlines check-in desk, unaware that the ticketing agents had been contacted by the FBI. As he chatted with the desk agent, DeSanto and Hawkins approached him, along with two of their male colleagues. He was “actually receptive and asked what was going on,” Hawkins recalled.

DeSanto told Rufai that he was under arrest, read him his rights and put him in handcuffs. Rufai pleaded guilty this year to wire fraud and aggravated identity theft. He was ordered to repay more than $600,000 and in September, he was sentenced to five years in prison. His Cartier watch and gold chain, which the Justice Department had valued at $45,000, were recently put up for auction by the federal government. The high bids for the items as of early December would repay less than 1 percent of his debt.