Jacob Leibenluft, Chief Recovery Officer

COVID-19 pushed families across the country to fall behind on their rent—many of whom already struggled with the cost of housing. At the end of 2020, nearly a fifth of renting households reported being behind on rent. One in six reported that eviction within two months was very likely.

Research has made clear the grave consequences of eviction for families. Evictions can interrupt school and work, undermine physical and mental health, and make it more challenging to qualify for housing assistance benefits or find new housing. Eviction can cause tenants to lose possessions, or face food insecurity.[1] As the pandemic destabilized life for many Americans, these risks grew even more serious.

But through the Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) program—created as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 and dramatically expanded by the American Rescue Plan—the Biden-Harris Administration put forward an unprecedented response to the eviction crisis the pandemic exacerbated. At the same time, ERA has helped lay the groundwork for lasting eviction prevention infrastructure and new investments in affordable housing.

According to the data released by the Treasury Department today, as of the end of 2022, nearly 10.8 million rental assistance payments have been delivered to renters in need. And supported by program guidance and technical assistance the Administration has spearheaded, communities have moved quickly to deploy ERA to aid renters at risk of eviction.

For renting families, the impact of these efforts has been enormous. In conjunction with other policies the Biden-Harris Administration has pursued, ERA helped to keep more than a million Americans in their homes in 2021 alone.[2] Assistance has benefited marginalized communities in particular: extremely low-income renters have received close to two-thirds of ERA assistance, while Black families have received 46 percent, and female renters have received nearly 70 percent.[3]

We know there is more to do to keep renters in their homes, and more to do to administer ERA. But even so, over the past two years, ERA’s impact is clear. As Matthew Desmond—the author of Evicted and founder of Princeton University’s Eviction Lab—has reflected:

The Emergency Rental Assistance Program along with the federal eviction moratorium formed the most important federal housing policy in the last decade. These combined initiatives were the deepest investment in low-income renters the federal government has made since the nation launched its public housing system.

COVID-19’s Threat to Families in Rental Housing

Even before COVID-19 emerged, Americans faced an eviction crisis rooted in the high cost of housing. As of 2018, nearly half of renter households were cost-burdened, paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent, while one in four households below the poverty line spent more than 70 percent of their income on housing. Evictions were frequent: between 2000 and 2016, Americans faced 3.6 million evictions each year on average, with seven evictions filed every minute in 2016.[4] Policy support for renters facing eviction—such as eviction diversion programs—was also relatively rare.

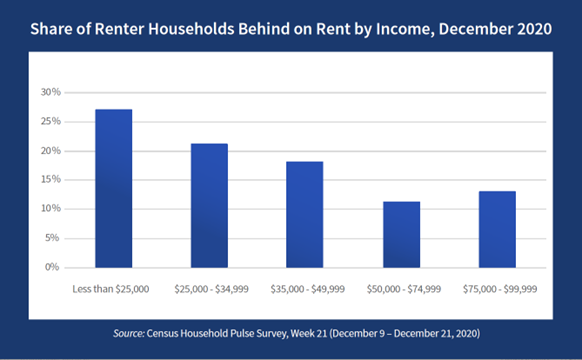

In 2020, the pandemic took this existing crisis and intensified it enormously. By December of that year, nearly nine million households were behind on rent. Low-income Americans and Americans of color were especially likely to face housing instability, with 16 percent of Black renters and 11 percent of Hispanic renters reporting that eviction was likely.[5] Moreover, the pandemic meant that housing instability could pose new, serious risks to families’ health, especially seniors.

With so many renters unable to pay rent, landlords saw incomes fall, too—especially the many smaller landlords renting only a few units. From 2019 to 2020, the proportion of landlords collecting 90 percent or more of rent dropped by nearly a third, with the smallest landlords facing the deepest arrearages.[6]

The pandemic thus put renters and landlords under enormous stress. And while the federal eviction moratorium was a powerful stopgap tool for keeping Americans in their homes, it was only a temporary solution. The moratorium gave many hard-pressed renter families with lost income more time to pay bills without fear of eviction. But it did not directly assist renters as they tried to catch back up on payments. Nor could it make their landlords whole, or help to repair the rent flows on which a functioning rental housing market ultimately relies. As COVID-19 persisted, it was increasingly clear that low-income renters needed access to direct financial support if rental housing were to begin to stabilize and recover.

Standing Up ERA

Against this backdrop, Congress established the two component pieces of ERA: first, the initial $25 billion program in December 2020, now called ERA1, and then a $21.55 billion expansion as part of the American Rescue Plan, now called ERA2. Tasked with administering these programs, Treasury confronted a race against the clock as millions of Americans faced the risk of eviction and landlords struggled with lost income.

As Treasury disbursed billions of dollars to state, local, Tribal, and territorial governments, we worked to stand up rental assistance program infrastructure that had never existed before. Treasury developed and communicated program guidance to help grantees understand essential program parameters and speed assistance. Staff spoke with hundreds of governments to discuss their experiences and offer technical guidance. And through wide-ranging outreach efforts—including a first-ever White House Eviction Prevention Summit in June 2021, and roundtables between grantees and senior Treasury leaders—Treasury and other partners across the Administration highlighted best practices. Treasury also published an array of promising practices highlighting successful program design features, and worked closely with community groups, advocates, and other stakeholders to drive their adoption.

These efforts positioned grantees to swiftly deliver rental assistance to renters in need:

- In Pierce County, WA, which had no pre-existing rental assistance program, ERA program leaders moved swiftly to stand up the County’s program. To facilitate application processing, the County developed an online portal that opened in March 2021. Pierce County hosted webinars with landlords and tenants, held events at public libraries and low-income housing facilities, and partnered with other jurisdictions and nonprofits to efficiently deliver assistance while limiting duplicative services.

- The State of Alaska, the Municipality of Anchorage, and 15 agencies representing 148 Tribes collaboratively developed a standardized mobile-friendly application system. They launched their application in mid-February 2021 and used five nonprofit providers from across the state to engage in outreach. The collaborative planning and implementation approach led to one third of renters within Alaska applying to the program, with Alaska Native/American Indian renters representing 28 percent of applicants.

Leveraging Flexibilities to Reach Renters

Even as the first rental assistance payments began to reach renters and grantees developed experience and capacity, Treasury continued to strengthen its policy guidance. We worked to provide programs an increasingly broad range of flexible tools to meet the need for assistance in their communities:

- Guidance additions in May 2021 permitted ERA funds to be used not only for rent, but also expenses involved in finding new housing, like security deposits—costs tightly linked to housing stability. Guidance also provided a new tool for establishing applicants’ income by allowing programs to verify renters’ income through reasonable proxies, such as the average income in a renter’s neighborhood.

- In June 2021, Treasury released guidance detailing how grantees could work with utility providers and landlords to speed assistance when a utility or landlord served multiple households eligible for assistance.

- In August 2021, Treasury expanded guidance to clarify that grantees could rely on self-attestation to document a household’s ERA eligibility when reasonable validation or fraud-prevention procedures were in place. Guidance additions allowed ERA funds to be used for rental or utility arrears at previous addresses, recognizing that such arrearages could create a significant obstacle to finding new housing opportunities.

Alongside work to strengthen its guidance, Treasury moved to improve program capacity, publishing additional promising practices on critical program issues and supporting grantees with technical assistance as they worked to implement flexibilities. We also worked to encourage partnerships between grantees, court systems, and other groups to promote access to ERA funds among renters.

Treasury designed guidance flexibilities to ensure that grantees safeguarded the integrity of their ERA programs. For instance, when Treasury allowed grantees to rely on household income determinations made in connection with other government programs—what we called “categorical eligibility”—Treasury leveraged verifications other agencies had already made. Treasury guidance required grantees to reassess a household’s income every three months if a grantee relied on a renter’s self-attestation alone to document their income. And Treasury required grantees to impose controls to ensure compliance with eligibility policies and procedures, as well as to prevent fraud.

These flexibilities and outreach efforts led assistance expenditures to increase rapidly throughout 2021. In the words of housing officials in Hennepin County, MN, “flexibility allowed us to respond quickly to rising need.”

Because of these efforts, when the federal eviction moratorium was lifted in August 2021, grantees were positioned to respond rapidly. Instead of the alarming spike in evictions that many feared, eviction filings remained below their historical averages. Data from the Eviction Lab suggests that evictions remained roughly 23 percent below historic averages in the first full year following the end of the national eviction moratorium.

Accelerating Assistance through Reallocation

As we reviewed grantees’ performance in 2021, it became clear that many had leveraged flexibilities and adopted best practices, allowing them to rapidly disburse assistance to renters in need. Other grantees, however, struggled to implement successful program designs and had fallen off track, limiting access to assistance and creating risk that funds wouldn’t be promptly expended. Further, in some cases, grantees received more funds than were realistically needed in their area over the short term, even if they had administered strong programs.

The ERA statutes anticipated these dynamics and required Treasury to “reallocate” funds—to shift ERA resources between jurisdictions, consistent with a grantee’s demonstrated need for assistance.

Since it began in fall 2021, Treasury’s reallocation work has allowed us to shift more than $4.3 billion that may have otherwise gone unspent. At the same time, reallocation has spurred the adoption of best practices and strong program designs that have speeded assistance payments.

Treasury has worked cooperatively with grantees to best utilize reallocation. For instance, ERA1 reallocation guidance encouraged best practices by allowing low-performing grantees to submit plans to strengthen their programs. If plans were approved—and over 140 were—grantees could retain certain funds that would otherwise be reallocated.

Treasury has also encouraged and prioritized voluntary reallocation—that is, allowing grantees to voluntarily redirect ERA funds to another grantee, most often serving communities near or within their jurisdictions. Voluntary reallocation has enabled grantees to work together to shift funds to where they can be best used, and recipients of voluntary reallocation have included states, counties, cities, and Tribes.

While we sought to route funds to areas with high demonstrated need and robust programs, Treasury also prioritized keeping funds within the states to which they were originally allocated. We did so because when reallocated funds stay in an area, they frequently remain available to the same or a similar pool of renters. For example, a slow-performing city might voluntarily reallocate funds to its state’s higher-performing program, or a state could reallocate unneeded funds to Tribal grantees. In-state reallocation thus has promoted access to rental assistance in areas with governments that may have lost funds in our reallocation process due to their program performance.

A Legacy of Reform

Today, ERA programs serve communities across the country, and Treasury is committed to working with grantees to continue ERA’s success as the programs move forward. But even as ERA remains ongoing, we can already start to see the legacy that this investment in housing stability will leave behind.

At the outset of the pandemic, only a few dozen jurisdictions operated rental assistance programs or eviction diversion programs. But the Biden-Harris Administration has led an unprecedented push for reform. In addition to our work at Treasury, the White House hosted summits on eviction diversion to encourage best practices, Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta wrote to state courts to urge the creation of eviction diversion programs, and 99 law schools began or broadened eviction legal clinics as part of an Administration-led initiative.

These efforts have set off a profound shift in eviction-prevention policies across the country. Leveraging funds from ERA, as well as other recovery funds from the American Rescue Plan, communities have dramatically expanded their support for renters. Interventions like eviction diversion provide landlord-tenant mediation programs and equip tenants with resources. Expanded access to counsel offers tenants support and advocacy as they navigate evictions proceedings.

Roughly 180 jurisdictions have developed or strengthened eviction diversion programs. Nearly 60 cities have used federal funds to expand access to counsel for tenants facing eviction. And since January 2021, 31 states and 81 localities have passed or implemented more than 180 tenant protections.[7] For example:

- The State of Oregon has supplemented its ERA funding with funding from Treasury’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund, as well as the state’s own funds. It also now operates the Eviction Prevention Rapid Response Program, which provides rapid financial assistance to prevent eviction and homelessness.

- Boulder, CO has launched an eviction prevention program funded with tax revenue that assists renters with housing issues through legal representation, rental assistance, and mediation services.

Each of these programs or policies represents a critical protection for renters in a community; together, they reflect a historic step forward. As ERA concludes, governments have the opportunity to continue to invest in these programs, including potentially with funds available through the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund that Treasury administers. Already, SLFRF recipients have served more than 3.6 million households with rent, mortgage, or utility aid. And jurisdictions have leveraged both SLFRF and ERA to address long-term housing supply challenges through investments in affordable housing, including over $5.4 billion of SLFRF funds committed to affordable housing development and preservation.

President Biden’s Budget also provides $3 billion for efforts to build on ERA and further build out eviction infrastructure. It includes funding for eviction diversion programs, rental assistance, expanded access to counsel, and other resources for tenants facing eviction.

* * *

Throughout ERA, renters have been the most important witnesses to the impact of the program for families. One renter told a grantee that “[r]ent help saved me and my kids from being out in the cold and homeless.” Another said that “[w]ithout you, I couldn’t have continued my cancer treatment, if I had become homeless.” As we reflect back on ERA, we remember that these stories are the ultimate measure of the program, as well as critical illustrations of the importance of housing stability to families.

The successes of ERA to date would not have been possible without the remarkable efforts of state, local, Tribal, and territorial government grantees to drive on the ground the achievements of the ERA programs—and we are enormously grateful for their partnership.

Looking ahead, we know important work remains, both to support grantees throughout the lifetime of the ERA grants, and also to push forward eviction policies and programs that promote housing stability. But on the second anniversary of ARP’s ERA expansion, we also believe we can look back at a program that has served millions of Americans and helped to overcome an unprecedented housing challenge.

[1] See, e.g., Matthew Desmond, Evicted (New York: 2016), 295-99 (summarizing research on toll of eviction).