Given the constraints on public sector borrowing in the UK, the new Labour government wants a substantial increase in private sector infrastructure investment. This could include investments under licence, investment in privatised utilities and public-private partnerships to invest in public services and develop new technologies to further the green transition.

For investment to take place on any scale, non-government investors will need to be confident of adequate returns. To achieve desired returns investors will need reassurance on the prices of these services, which in turn will probably mean that consumers pay more than they currently expect unless the government subsidises consumer charges (which would frustrate the objective of relieving the pressure on public sector finances).

A significant increase in privately financed investment in infrastructure makes even more urgent the need for a marked improvement in the performance of regulators, particularly in monitoring and controlling the financial strength of service providers. The collapse of several energy providers following the rise in world fuel prices and the current financial weakness of some water companies would not have occurred if their finances had been adequately supervised.

The government will have to take care how its investments are scored by the statistical authorities. Some transactions could be classified as adding to government borrowing, even though that is not always the case in comparable economies, thus frustrating the aim of controlling the public finances.

Understandable wariness over increasing public borrowing

The government is right to be cautious about borrowing even more than currently envisaged given the high level of the UK’s debt to gross domestic product ratio. Once markets lose confidence in the soundness of government policy – as in the run up to recourse to the International Monetary Fund in 1976 and briefly during the Liz Truss episode in 2022 – it is difficult for the government to increase borrowing even to finance investment.

There may be some tax increases that do not break manifesto pledges and some other changes (notably to its financial arrangements with the Bank of England) that increase fiscal ‘headroom’ and make possible some modest increases in public investment. But such changes are unlikely to be sufficient to finance anything like the desired increase in infrastructure investment.

Advocates of privately financed investment have emphasised the benefits flowing from private sector expertise in the provision of services. There is another powerful argument for financing investment other than purely through gilt sales. Involvement of the private sector in the delivery of services makes possible recourse to other forms of finance – equity as well as senior debt – and providers of finance that might have a limited appetite for UK gilts, for instance sovereign funds, large pension funds (not necessarily from the UK) and a variety of banks.

Such investors will only contribute to increasing infrastructure investment if they can earn what they consider appropriate returns on capital, which in turn will involve large price increases. The 2023 auction for offshore wind licences failed because the price offered was too low. The water industry believes that it needs to invest much more than is currently proposed by the regulator if it is to deal adequately with wastewater and sewage. This in turn would involve significantly higher price rises than the regulator or government want. If private finance is to be used to ramp up investment in hospitals and schools, potential private sector partners will want assured returns over the life of their investments, which will be a charge on future health and education budgets.

The National Wealth Fund – a relatively modest £7.3 billion over five years – is intended to lever in around £20bn of private sector investment. While the new fund, introduced by Chancellor Rachel Reeves, may finance the riskier early stages of projects, the private sector will still want a reasonably assured return on its investment.

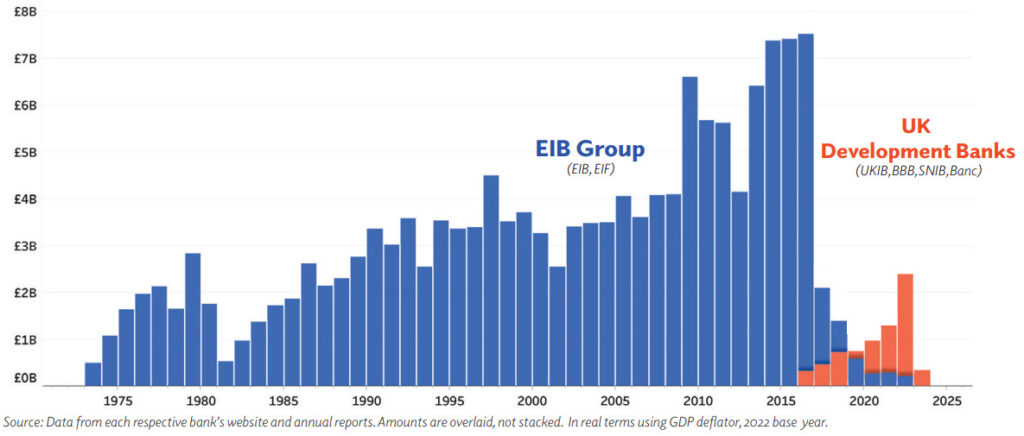

It is worth noting that the activities of the UK Infrastructure Bank, which will manage the new fund, would not come near to replacing the pre-Brexit lending by the European Investment Bank. According to a study by UK in a Changing Europe, EIB investment in UK infrastructure averaged around £6bn per annum in real terms while the UK was in the EU (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Since leaving the EU, the UK has only been able to replace a third of public investment

Annual investment into the UK including private and public loans, equity investments and guarantees by development banks in real terms in £bn

Source: UK in a Changing Europe

Note: The chart data were collated before the announcement of the National Wealth Fund.

Regulators must help to manage customer dissatisfaction

Particularly in the energy and water sectors, adequate returns for private investors will depend overwhelmingly on the ability to raise prices for consumers. This will be difficult because consumers tend to think that they are already paying – or even overpaying – for the services that increased investment will make possible even when they are not. There is a real danger of falling between two stools with a combination of increased but insufficient investment and unpopular price increases.

Improved performance by the regulators might reduce consumer dissatisfaction somewhat. It is now clearer than at the time of the original privatisations that infrastructure regulators need the skills of banking and financial sector regulators as well as detailed knowledge of their industries. Regulators need to monitor and control the financial structures of their companies, preventing over-leverage, irresponsible dividend payments and excessive executive remuneration where performance is poor. In the energy sector the regulators and the companies need expertise on how to act effectively and prudently in futures markets.

As one of the overt objectives of encouraging private sector financing of infrastructure is to avoid additional government borrowing, it will be essential to ensure the various ways that the use of private finance is developed do not run the risk of the finance being classified as public sector. Without a substantial transfer of risk, which implies high returns on the private finance, it is highly likely that private finance schemes for health and education would be classified as public sector, thus destroying the principal reason for the exercise. It would be sensible to restrict the use of private finance to those areas of infrastructure where there is less risk of private finance being classified as such.

Finally, market perceptions of the responsibility or otherwise of UK fiscal policy rely to a great extent on international comparisons with peer economies. But government support for infrastructure is not a level playing field. While the UK Infrastructure Bank is treated as part of the public sector, this is not the case for public sector lenders in every country, notably with KFW in Germany. An exercise to produce comparable measures of public borrowing in peer economies is overdue.

Peter Sedgwick was a senior UK Treasury official, Vice President of the European Investment Bank from 2000-06, Chair of 3i Infrastructure PLC from 2007-15 and Chair of the Guernsey Financial Stability Committee 2016-19.