Ever since the financial crisis of 2007-08, British banks have often struggled to make as much money as they used to. Profits have generally been at a much lower level than in the pre-crisis period.

But in recent weeks, some of the best-known banks in the UK have reported big jumps. Europe’s biggest bank, HSBC, posted close to an 80% rise in pre-tax profits of £24 billion for 2023. Lloyds said it was up 57% to £7.5 billion.

So, are British banks finally heading back to their glory days?

Certainly, these increases seem to be well timed for many bankers, as they coincide with the axeing of the cap on bankers’ bonuses. That cap was introduced after the financial crisis as part of efforts to curb reckless and risky behaviour by bankers, who were often focused on maximising short-term profits. And research has shown a direct link between executive pay and excessive risk-taking by banks.

But the recent surge in profits does not mean they will necessarily continue. One of the main reasons banks made so much money last year was the steady rise in the Bank of England base rate since the end of 2021. That rate went from 0.25% to its current level of 5.25%.

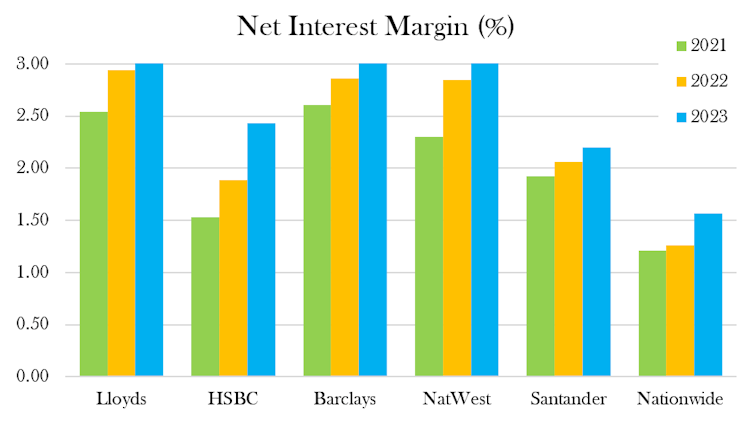

And it was these rates hikes which allowed banks to boost their “net interest” margins – the difference between the interest a bank receives on loans and the rate it pays for deposits. This is the big banks’ main source of income.

Author provided (no reuse)

Swift adjustments to the interest rates charged on all types of loan meant the average rate for a two-year fixed mortgage (with a 10% deposit) increased from 1.95% in December 2021 to 5.45% now. In contrast, the banks had to be nudged into passing on those rate increases to savers, who are still not fully benefiting from them – despite borrowers paying more.

But higher profits may be a temporary thing if, as is widely expected, the Bank on England starts cutting rates later this year. A fall in lending rates, coupled with the pressure to increase the interest paid on savings, will negatively affect higher net interest margins.

In fact, banks including NatWest and HSBC are already adjusting their future profit expectations to take into account falling interest rates.

Investments may fall

Another factor is that since the financial crisis, there has been a significant increase in the amount of capital that banks must hold on to (calculated as a varying percentage of assets). These rules were enforced after the financial crisis as a major regulatory change to make banks – and the overall financial system – safer. But higher capital requirements reduce profitability because of the amount of money that needs to be put aside.

It seems unlikely that these stringent requirements will be relaxed, despite the protests of some bank CEOs.

There are other factors too that may reduce bank profits. A recent Financial Conduct Authority probe related to banks’ car financing – when it is alleged consumers were charged higher interest rates on loans than they should have been – may also affect profits soon, if lenders are forced to pay billions in compensation.

Banks may also make losses, and need to put aside even more capital, for loans that may not be paid back due to the effects of the economic slowdown and cost of living crisis.

Banks with large Asian operations, such as HSBC and Standard Chartered, are also suffering from their exposure to China’s collapsing property market, which is expected to stifle profits. Heightened geopolitical tension in Ukraine, the Middle East and Taiwan, and Donald Trump’s potential return to the White House, are not helping either as they fuel an uncertain global economic outlook.

Read more:

Bankers bonus cap: why scrapping it could hurt the UK economy

So, the profits we have seen in recent weeks do not seem to be cause for much celebration in the City. And perhaps sensibly, banks appear to be viewing them as a temporary lift and appear more focused on reducing costs.

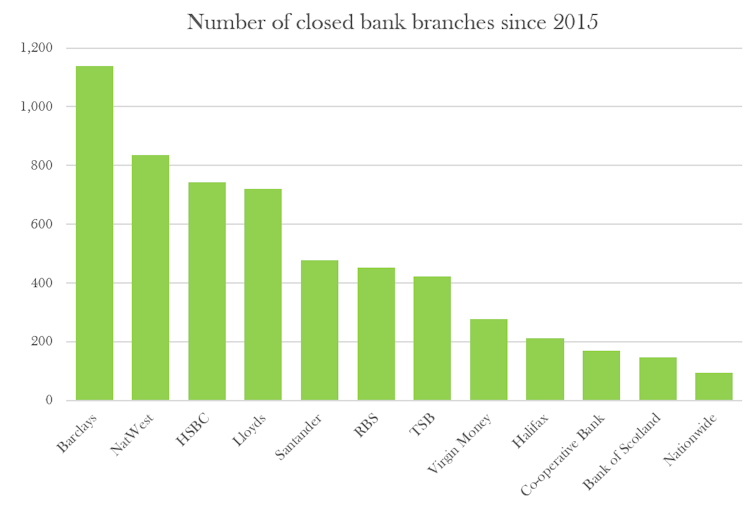

For example, they have been cutting back on expensive elements of their business. Since 2015, 5,835 bank branches – more than half the total number that used to exist – have closed.

Author’s graph using data from Which?, Author provided (no reuse)

And cost reductions look set to continue in 2024. Lloyds recently announced more than 2,500 job cuts to restructure its business with a focus on digital services. Barclays and Santander may end up doing the same, while similar levels of redundancies have been seen in the US and the EU.

Overall, despite the increasing profits in the last two years, 2024 will be a challenging one for banks. Apart from the predicted impact of rate cuts on banks’ interest margins, economic growth in the UK and globally is expected to be very slow. That means less money moving around, which means less business for the banks and, ultimately, less profit.