Peter Jurkovic explores the UK’s green investment gap. He shows that the UK Investment Bank has not been able to replace green financing from the European Investment Bank and the Green Investment Bank and faces obstacles to doing so.

The UK has a green investment gap. According to the independent Climate Change Committee (CCC), in order to meet its 2050 net zero target, the UK will have to increase its low-carbon investment from £10bn per year in 2020 to around £50bn per year by 2030. And Brexit may have made this an even greater challenge.

The problem with the kinds of green investments needed to transition to net zero is that they are often unappealing to the private sector. Climate projects tend to involve large upfront costs without the promise of short-term returns. There is also uncertainty about the effectiveness of many green technologies and about the future of some low-carbon infrastructure projects in a constantly changing policy landscape.

Enter public investment banks, which are often more willing to provide capital to these kinds of projects. They are state-owned and so mandated to achieve specific socio-economic goals rather than solely make money. Public investment banks can therefore provide ‘patient financing’ – long-term financing with no need for high returns in the short-term.

In the UK, two such banks were heavily involved in financing climate infrastructure projects. The Green Investment Bank (GIB) was established in 2012 by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government with the explicit goal of providing finance to help the UK to meet its emission targets. The European Investment Bank (EIB) also provided the UK with a significant amount of finance for climate related projects in the 2010s.

These banks were particularly important in helping the UK to develop its onshore and offshore wind industries, as well as in supporting local governments to make energy efficiency measures in infrastructure and housing.

However, neither is now operating in the UK. The GIB was sold by the government to a consortium led by the Macquarie Group Ltd in 2017 and the UK lost access to EIB finance when it left the EU in 2020.

So far, they have not been successfully replaced.

In 2021, the government established the UK Infrastructure Bank, providing it with £22bn of capital (spread out over at least five years) and giving it an explicit objective of supporting the transition to net-zero.

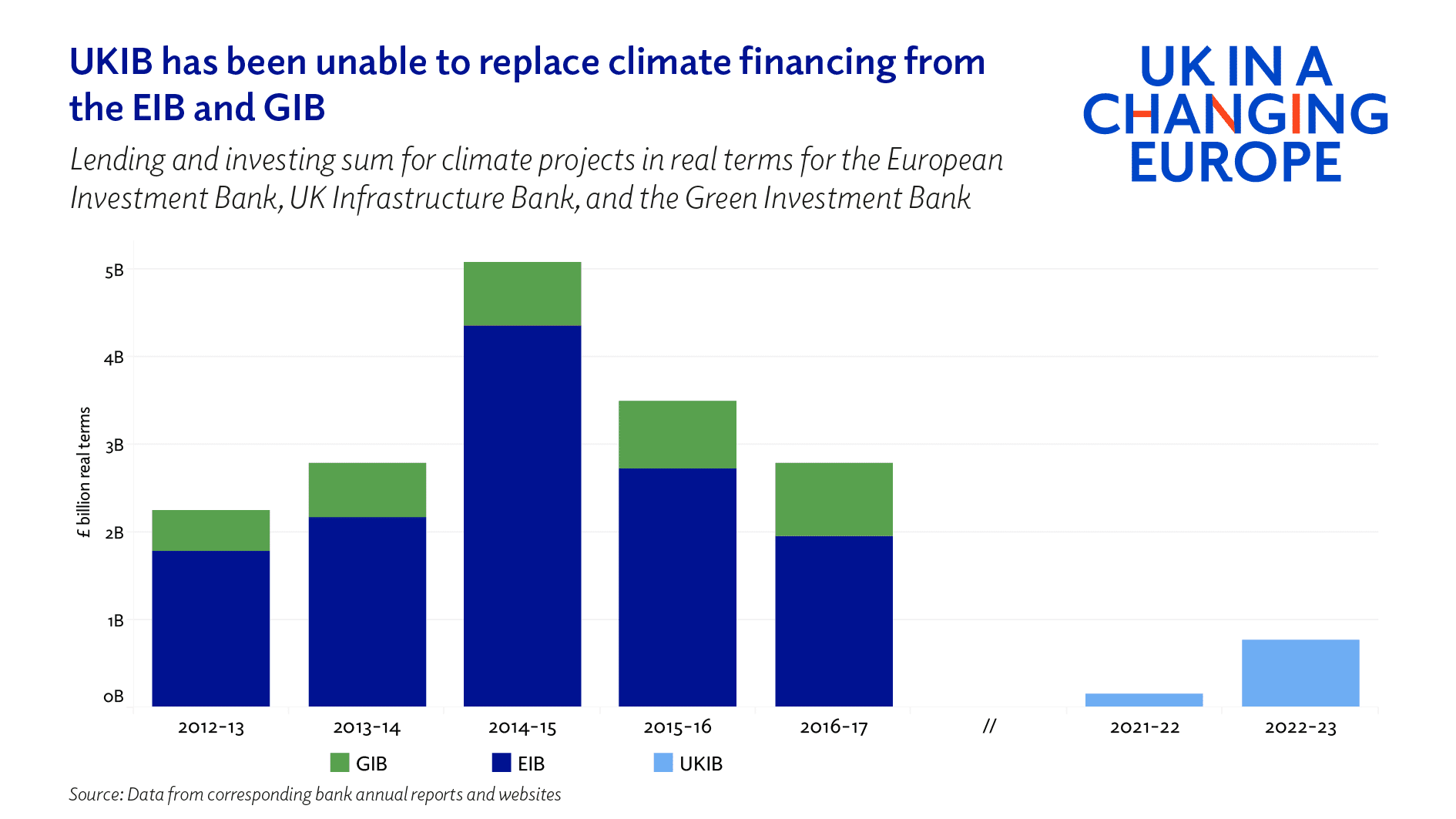

But the UKIB has only provided around £0.9bn of lending and investment to support the UK’s transition to a green economy. This sum is well below that provided by the GIB and the EIB, which together invested over £17bn (in real terms) in climate projects from 2012 to 2017. The problem becomes clearer if we consider how much the UK could currently be receiving from the EIB. In 2022, just for climate projects, France received €5.9bn and Germany received around €4.4bn from the EIB. As these countries held the same share capital as the UK did, the UK could have expected to receive a similar sum today.

This does not mean the UK cannot replace this finance. There are examples of public investment banks, such as the KfW in Germany and the BNDES in Brazil, which have played an important role in the low carbon transition.

The main issue for the UK’s new public investment bank is that it is currently under-resourced. The UKIB has fallen short of its target of 320 employees – it currently employs only 207 members of staff, of whom 90 are permanent. In comparison, the KfW in Germany has nearly 8,000 employees.

This has meant that the UKIB currently lacks the necessary expertise and governance structures to take the investment risks that the private sector avoids. As a result, the UKIB is not filling gaps in climate infrastructure investment.

Instead, it has generally opted for investments in lower-risk broadband infrastructure projects, which can usually find finance from private investors. In other cases, it has outsourced the responsibility of making direct investments by channelling finance into third-party funds. This, however, gives the bank little control over the projects to which its finance is directed.

The UKIB faces other obstacles to scaling up green investment. First, the current cap set by the Treasury on the amount that it can borrow (£1.5bn per year), will prevent it from significantly leveraging its balance sheet. Second, it is not yet clear how much of the UKIB’s investment earnings the Treasury will permit it to retain.

While these limits remain in place, the UKIB will be unable to dramatically scale up its financial capacity. And, consequently, it will be prevented from playing a significant role in the UK’s transition to net zero.

By Peter Jurkovic, researcher, UK in a Changing Europe.