Stephen Hunsaker and Peter Jurkovic explain what the European Investment Bank is, how it is structured and the role it played in the UK economy before Brexit.

For more on development banks, you can find our new report on UK development banks post-Brexit here.

What is the European Investment Bank?

The European Investment Bank (EIB) is the world’s largest multilateral financial institution and a leading financial provider within the European Union.

The EIB was established in 1958 under the Treaty of Rome and has since invested over a trillion euros in more than 135 non-EU countries. However, the EU has always been its primary focus, with approximately 90% of finance going to member states. It is jointly owned by EU member states, and it is these states, rather than the EU, which provide the EIB with its resources through paid-in capital.

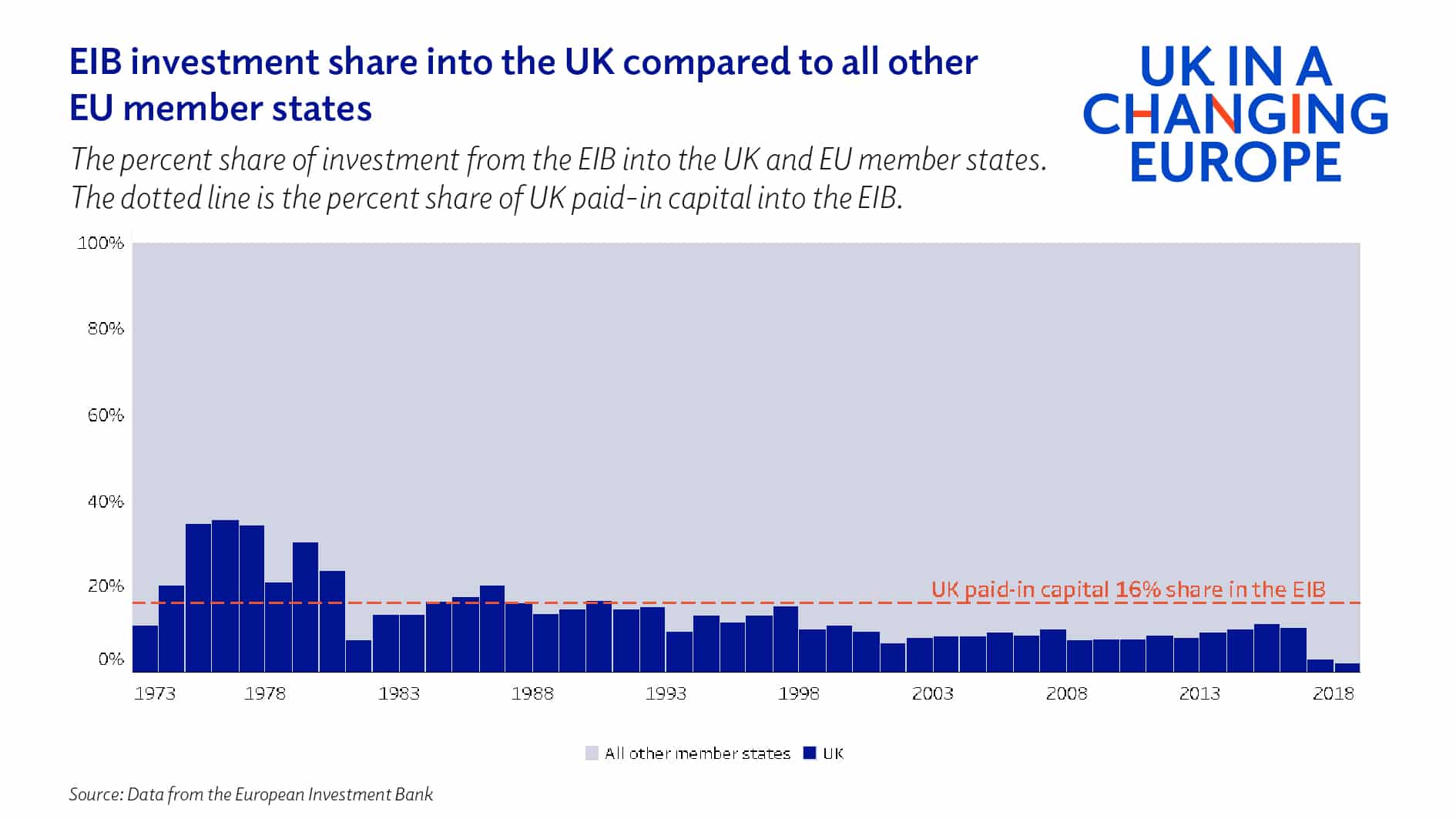

Each member state’s shareholding is based on the relative size of its GDP at the time of its accession, with the three largest economies (France, Germany, and Italy) being capped at 16%. Together with Spain, these member states represent more than 68% of the EIB’s capital.

The initial mandate of the EIB was supporting EU cohesion and the single market. Since that time, it has expanded to fostering sustainable growth within the EU and abroad by supporting projects that also promote the priorities and objectives of the EU.

In 1993, the EIB expanded with the creation of the European Investment Fund (EIF) to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). And then in 2000, the EIB expanded into the EIB Group, made up of the EIB, European Investment Fund (EIF), and the EIB Institute which was created to work on social and cultural initiatives. The EIB remains the primary investment arm of the EIB Group with a focus on infrastructure, while the EIF is the venture capital arm focused on SMEs.

The EIB has over 4,000 employees after a significant expansion over the last decade, which saw the bank increase its staff numbers by almost 1,000. This has allowed the bank to finance more technical and sector-specific projects.

What is the governance structure of the EIB?

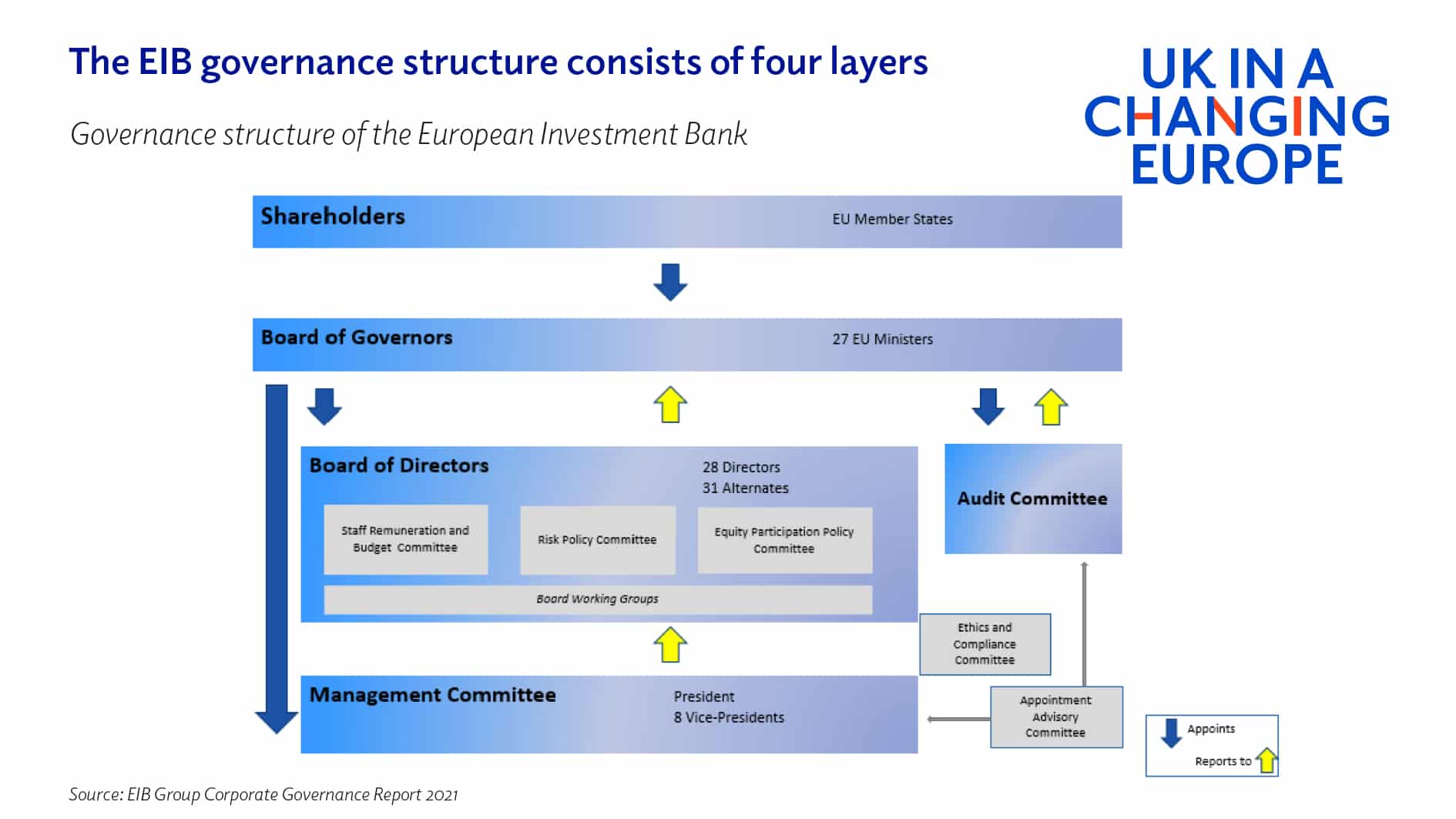

The EIB has four layers of governance.

- The Board of Governors is made up of ministers (usually the finance minister) from each of the EU member states. This body develops the bank’s guiding principles, credit policy guidelines, and decides on capital increases. Decisions by the Board of Governors must be supported by a majority of its members, and over 50% of the bank’s subscribed capital.

- The Board of Directors has 28 Directors, with one elected by each member state and an additional director chosen by the European Commission. This body is responsible for approving all of the EIB’s decisions to grant finance as well as the bank’s overall politics and operational strategy.

- The Management Committee controls the day-to-day management of the Bank. It has one President and eight Vice-Presidents who are appointed by the Board of Governors.

- The Audit Committee is an independent body, which assesses annually whether the Bank’s activities meet best banking practice and its books are kept in order.

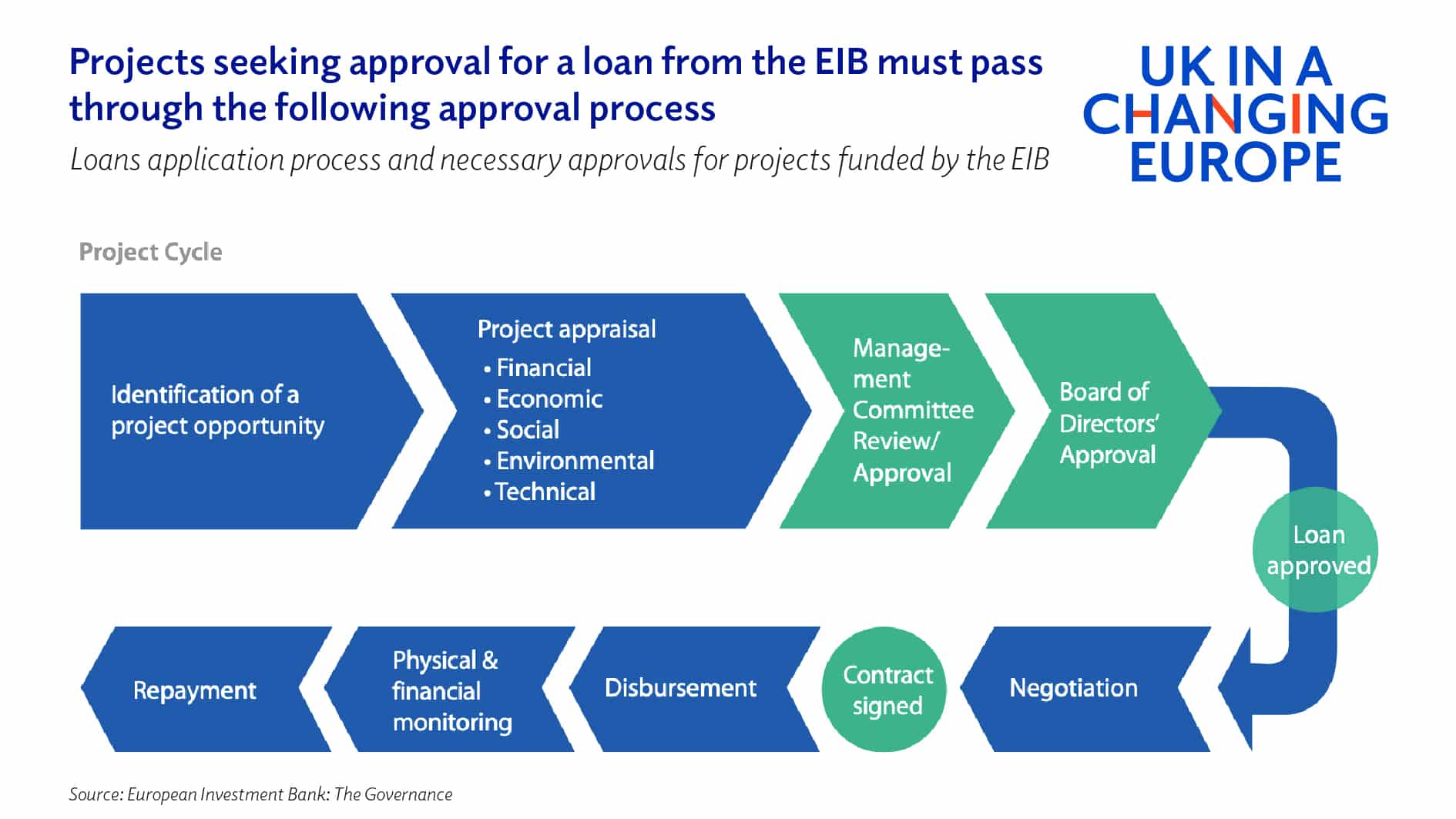

Loan applications can be made directly to the Bank, or indirectly through the member state where the project is taking place.

As part of the application, project promoters first send a request to the EIB for financing. The appraisal then considers the risk, financial benefit to the project, sustainability, economic and technical viability (unique to the EIB), and compatibility of the proposed project with EU policies.

The Management Committee then reviews the project and presents it to the Board of Directors to review. Both the EU Commission and the member state where the project is taking place have a veto over the Bank’s financing. However, vetoes are rare.

It is a deliberate policy of the EIB that member states do not themselves propose projects to the bank. This ensures that there is no favouritism of any certain member state in the project cycle. However, member states are still informed of the project and have a right to a veto. This is covered in Article 19 of the Statute, which states that the EIB shall request the EU Commission and the member state’s opinion on all financial operations.

The EIB monitors the progress of the project from its approval to completion. The Operations Evaluation division then evaluates the extent to which the project delivers the benefits that were anticipated by the bank. The EIB also monitors for risk of default, however, this is rare, with only 3.7% of private projects defaulting.

Why is the AAA credit rating so important to the EIB?

As a bank, the EIB offers loans, guarantees, equity investments, and advisory services, to support public and private sector partnerships, with a focus on innovation, climate, energy, infrastructure and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Normally, the EIB will provide a long-term loan of no more than 50% of the project’s defined eligible investment cost, typically providing around 30%. For investments in equity funds, the EIB will usually cover 10-20% of the fund size, with a maximum of 25%.

Like many development banks, the EIB holds a very high credit rating of AAA. Typically, a bond issuer will have a rating from at least one or two of the Big Three credit agencies. The EIB has a AAA rating from all three agencies – a perfect rating which (as of June 2023) is only held by the governments of nine countries and a few companies such as Microsoft.

The EIB leverages the capital that is provided by all EU member states to then borrow on international markets by issuing bonds. On account of the bank’s extremely high credit rating, it can fund itself very cheaply and, therefore, on-lend to counterparts by providing project loans at lower interest rates.

However, the EIB is an illustrative case of how the pursuit of high-credit ratings can also impede the ‘additionality’ function of development banks. A high credit rating allows development banks to borrow cheaply and, consequently, offer loans at lower costs to projects. However, out of fear of losing this rating, these banks may be discouraged from financing higher-risk projects and instead, opt for safer investments that were likely to have been covered by the private sector.

This has been a particularly contentious issue for the EIB. NGOs as well as some leaders of smaller EU member states have criticised the EIB’s ‘obsession’ with its AAA rating. They argue that this has caused the bank to opt for financing more advanced economies such as Germany, where there is a guarantee of greater returns, and neglect the EU’s smaller economies. However, the EIB may respond that its ‘obsession’ with its AAA rating is necessary. It is the EIB’s AAA rating that allows it to provide large loans at low interest rates, which has allowed it to become the largest development bank.

So, although the EIB claims that it aims to target support to less developed regions, from 2014-20, only 30% of the EIB’s investment designated for the EU went to ‘cohesion regions’ (regions with a GDP per capita below the EU average). Since then, in 2021, the EIB adopted a new ‘Cohesion Orientation’ which sets out a non-binding target for 45% of its lending to member states to go to cohesion regions.

Schemes such as the Investment Plan for Europe (Juncker Plan) have also attempted to confront this issue and channel more finance to projects with higher-risk. While the EIB was already financing more technical higher-risk projects, this scheme gave €16 billion in guarantees from the EU budget (with certain conditions on where the funds can be directed) to the EIB to push the bank to lend more to projects with a higher-risk profile.

The fear of a rating downgrade is only one reason for more cautious lending: another reason for opting for safer investments also comes from the concern of being accused of acting recklessly with taxpayers’ money by making loss-making investments.

What role did the EIB play in the UK economy?

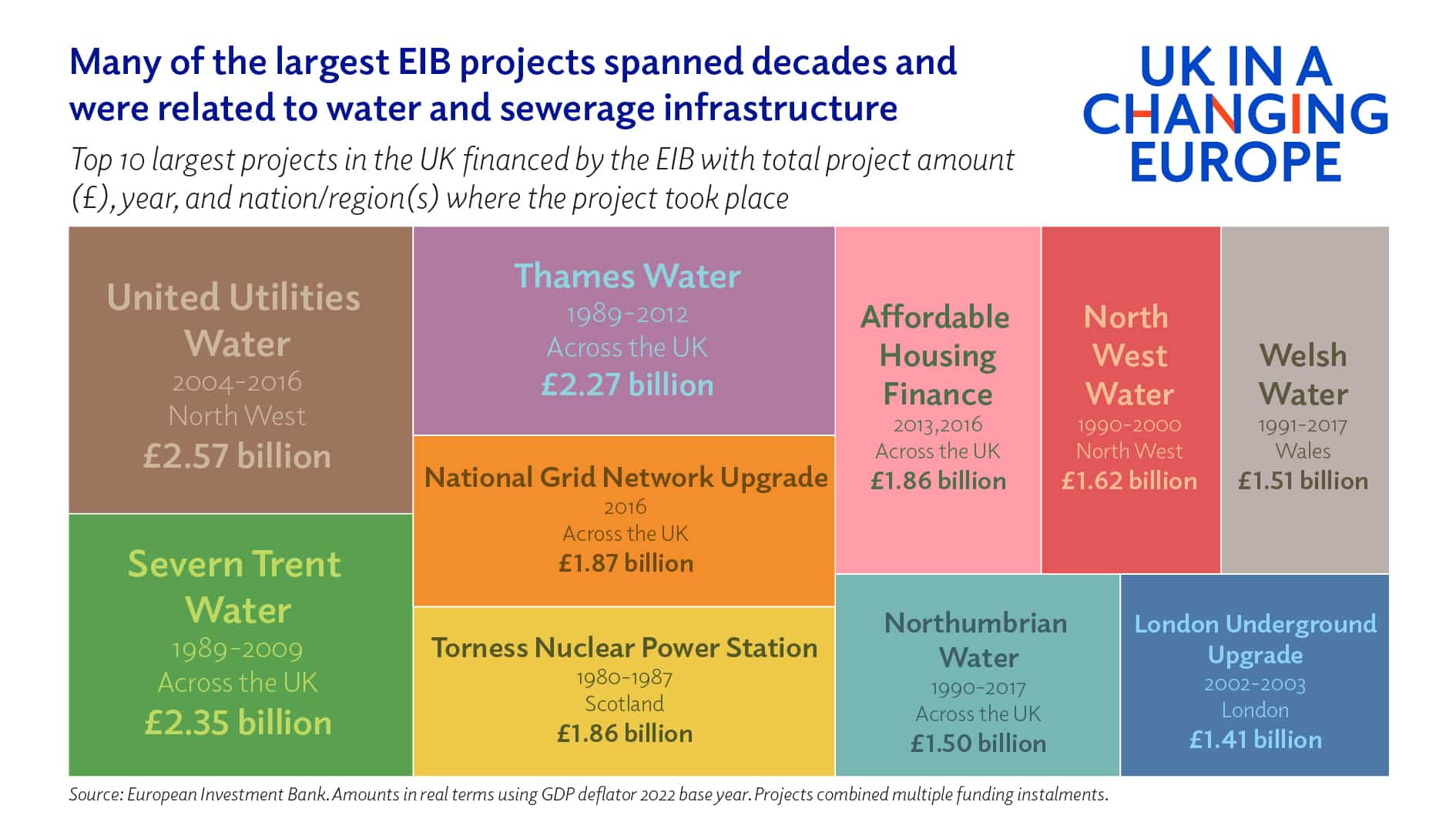

Since 1973, the EIB has invested £146 billion in real terms (£89 billion in nominal terms) in over 1,000 projects, many in infrastructure and energy, within the UK.

Over the nearly-50-year partnership, the EIB helped to finance many prominent projects such as the national grids network upgrade, the addition of the Channel Tunnel, Elizabeth Line, and Thames Tideway Tunnel, the second Severn crossing, the Manchester Metrolink extension, the renewal of rolling-stock for Mersey rail, the financing for the Royal Liverpool Hospital and Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, to the expansion of Aberdeen harbour. The EIB has covered every sector from transport, energy, health, and water to urban development, social housing, telecommunications, and waste disposal.

The largest UK projects that received EIB finance were in the water and sewerage sector. These projects were not financed all at once but over the course of many decades and across multiple regions, as water and sewerage projects tend to require a large amount of capital and commitment to finance them.

When the UK became a shareholder of the EIB, it provided €37.7 billion of subscribed capital (paid-in capital and callable capital). This was 16% of all subscribed capital, which was matched by Germany, France, and Italy.

Of the total subscribed capital €3.5 billion was paid-in capital. In addition, the UK had £34.2 billion of ‘callable capital’ in real terms. ‘Callable capital’ is a contingent liability or money which the UK was obliged to pay if the EIB suffered losses and it was unable to cover using its accumulated reserves. This was never used while the UK was a part of the EIB.

It was agreed in the Withdrawal Agreement that the EIB would pay that back to the UK in 12 annual instalments due to fact that projects still being financed in the UK held risk and therefore required partial paid-in capital to offset them while they were wrapped up.

In the two decades leading up to the referendum, the UK only received 9% of investment going from the EIB to member states (despite subscribing 16% of paid-in capital). At the beginning of its membership, the UK received a higher proportion of loans than its capital share – but successive waves of enlargement have meant that since 1990 the UK received a significantly lower proportion.

While the vast majority of funds coming into the UK from the EIB Group were from the EIB, the European Investment Fund (EIF), which supports SMEs, also contributed to the UK economy. Since its establishment the UK was its largest recipient, receiving over a third of its venture capital before Brexit. Between 2011 and 2015, 37% of the venture capital raised in the UK came from the EIF, suggesting it played an important role in the UK venture capital market overall.

The EIB also worked closely with local authorities across the UK to support the rollout of a variety of projects. One of the main schemes in this regard is the European Local Energy Assistance (ELENA) programme, which offers technical assistance for energy efficiency and renewable energy investments for buildings and urban transport.

It completed ten projects in the UK including working with Birmingham City Council to retrofit 7,500 houses and 80 public buildings and with the Cheshire East Council to carry out energy efficiency measures in public lighting systems and non-residential buildings.

By Stephen Hunsaker and Peter Jurkovic, researchers, UK in a Changing Europe.