First the good news

Some readers may be surprised to hear that the UK’s service exports now make up 48% of the UK’s total exports. It is rarely mentioned by the BBC or even by the Financial Times. Service Exports are divided by the ONS into twelve broad categories. The three largest of these are exported by ‘The City’ – Financial services, Insurance and Pensions, and Other Business Services – although the ‘City’ is not just in the Square Mile but now spreads all over the country including Canary Wharf, Birmingham, and Edinburgh. Together these three service industries account for over 60% of UK service exports and have been growing steadily since 2016 with Financial Service exports up 24%, Insurance and Pensions up 50% and Other Business Services up 72%. Much of the growth in these service exports has been to non-EU destinations.[i]

The US is by far the UK’s largest trading partner for ‘City’ exports. Exports to the US are as large, or in the case of Insurance and pensions twice as large, as export to all twenty-seven EU countries combined. But other non-EU markets for such service exports are also growing. Since 2016 Financial Service exports to China are up by 53%, to India by 62%, to Singapore by 100% and to Hong Kong by 127%.

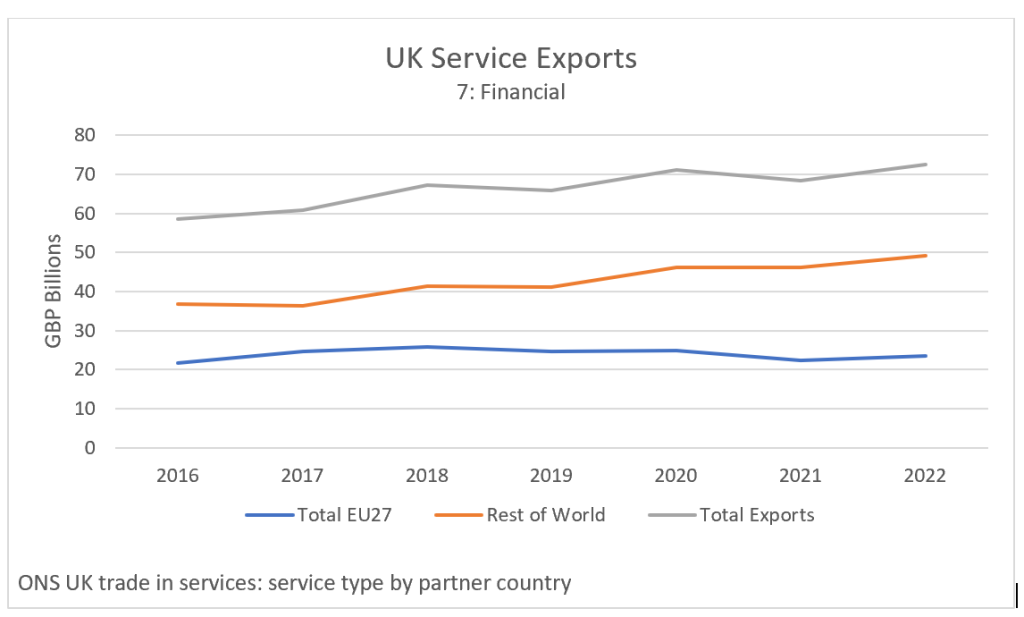

In total Financial Service exports increased by 33% to non-EU countries between 2016 and 2022 but by only 8% to EU countries. Financial Service exports to non-EU countries are now more than double the value of financial service exports to EU countries, as can be seen in the chart below:

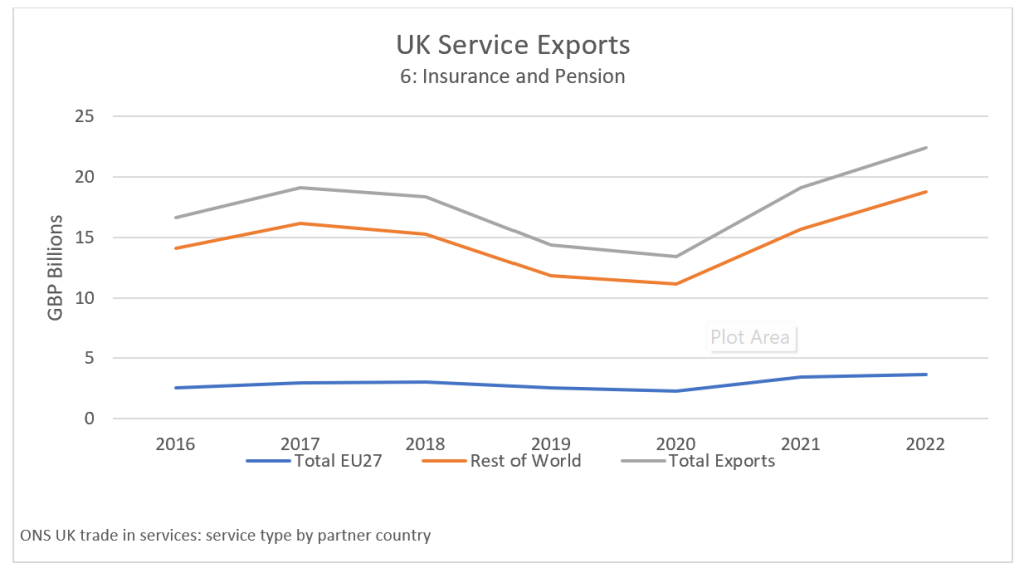

The UK’s Insurance and Pension exports have always been predominantly to non-EU countries which make up over 80% of the UK’s exports in this sector. This is due in part to the variety of insurance and reinsurance covered by UK firms. UK firms underwrite things such as catastrophe insurance, aircraft insurance, cargo insurance, as well as complex insurance covering construction contract overruns or covering errors and omissions for consultancy contract etc.

While UK investment managers have many long-standing agreements managing large US pension funds. However, exports to the EU in this sector are also growing and increased by 43% between 2016 and 2022, from £2.5 to £3.6 billion. Dare I say it….despite Brexit. This can be seen in the chart below:

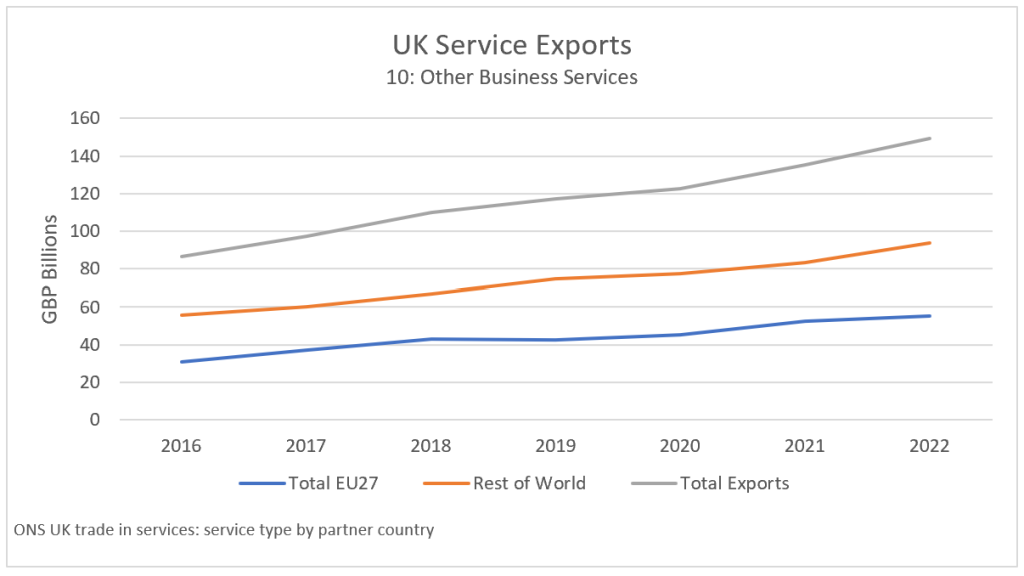

Finally, the star of UK service exports: Other Business Services, which grew by 72% between 2016 and 2022. As with the other service categories, the US is the UK’s largest export market in this sector with exports worth £52 billion in 2022, an increase of 136% since 2016. However, exports to other non-EU markets also increased between 2016 and 2022: exports to China increased by 77%, to India by 77% and to Canada by 166%.

Other Business Services are now not only the UK’s largest service export sector, but they are also larger than any goods export sector measure by either Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) or even the larger Standard International Trade Classification (SITC). In 2022 the UK exported £124.4 billion of SITC 7 Machinery and transport equipment, our largest goods export sector, but a massive £149.2 billion in Other Business Services.

Like Machinery and Transport equipment, Other Business Services is a very large category and includes legal services, accounting, management consulting and public relations as well as trade between affiliated enterprises and intergroup fees. In 2022 the UK’s two largest export subsectors were: 10.2.1.3 Business and management consulting and public relation services with exports worth £41 billion and 10.3.N59 Services between affiliated enterprises (not included elsewhere) worth £31 billion.

But now the bad news

While The City’s service exports are worth celebrating, the UK cannot be complacent that these businesses will remain in the UK indefinitely. Service businesses are generally large multinationals, with little plant and equipment or other infrastructure tying them to the UK. It would be very easy for these companies to move their business to other parts of the world if the UK ceases to be an ‘encouraging’ business environment as the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of AstraZeneca suggested when explaining his company’s decision to build their new pharmaceutical production facility in Ireland rather than the UK.[ii]

Some of the issues that could drive service businesses out of the UK are: taxation, regulations, productivity, management requirements and the UK’s anti industry energy regulations. If the UK is to remain a global financial centre, then it needs to be competitive with its rivals: New York, Singapore, Hong Kong, San Franciso, Los Angeles, Shanghai, Washington DC, Chicago and Geneva.[iii]

Taxation

The massive growth in Financial, Insurance and Pensions, and Other Business services mentioned above, has happened while the UK’s corporate taxes were 19%. In April this year corporate taxes were increased to 25% for companies who make more than £250,000 in profits. Small companies with profits below £50,000 remain on 19% tax rate. Companies with profits between £50,000 and £250,000 get marginal relief. While unit trusts and open-ended investment companies remain on 20% tax.[iv] And although the Government now allows full expensing of plant and equipment, most service industries don’t need large amounts of plant and equipment.

Such a large tax increase could easily drive service businesses out of the UK or simply encourage companies to book their profits elsewhere. Headline US Federal Corporate Tax is only 21% with a corporate minimum tax of 15%. Individual US states can also add corporate taxes: New York, headquarters of JPMorgan Chase the largest bank in the US, has a corporate tax rate of 7.25%, while North Carolina, headquarters of Bank of America, the 2nd largest bank in the US, has corporate taxes of only 2.5%. But there are several US states that have no corporate taxes: Texas, Washington, Wyoming, Ohio, Nevada and South Dakota.[v]

In other financial centres that rival the UK, taxes are even lower: Singapore’s corporate taxes are 17% with exemptions for 75% of the first S$10,000 and 50% of the next S$190,000 of income. The UAE’s corporate taxes are only 9% and Switzerland’s federal corporate tax rate is 8.5% and although some Swiss Cantons add additional corporate taxes, the effective combined tax rate is between 12% and 22%, both still lower than London.[vi]

Booking profits elsewhere is easy to do, as we have seen with US tech firms who run their profits through Ireland. Ireland’s corporate taxes are presently 12.5% and will increase to 15% in 2024. Ireland also has a much more generous business expense scheme, so most companies’ actual tax rate is generally much lower than the 12.5% headline rate. In 2021 Ireland’s largest corporate taxpayers were all companies normally thought of as US multinationals: Apple, Microsoft, Google, Pfizer, MSD (Merck, Sharpe and Dohme), Johnson & Johnson, Facebook, Intel, Medtronic and Coca-Cola.[vii] They also paid 53% of Ireland’s corporate taxes so it is in Ireland’s interest to encourage this practice.[viii]

Consequently, the UK Government shouldn’t imagine that legal profit diversion wouldn’t also happen from UK based companies. Even in 2022, Ireland was the largest recipient of UK exports of Services between affiliated enterprises n.i.e. receiving £8.7 billion, the US was the second largest recipient with £8.3 billion.

Regulations

Despite most of our Financial, Insurance and Business service exports going to non-EU countries, the UK is still laden with many EU regulations such as MiFID II, CRD IV, Solvency II etc. Much of this is in the process of being changed, but unfortunately very slowly.

However, when the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) wants a change, they can do so very quickly. For example, the ridiculous EU Double Volume Caps that hit UK equity trading more than any other market in the EU, were changed by Statutory Instrument and were no longer applied to UK stocks after December 2020 (the end of the UK EU Transition Period) and no longer applied to all stocks after March 2021.

The EU’s Double Volume Caps hit UK traded equities more than any other EU market because of the many investment managers based in the UK who manage enormous funds and need to buy and sell large volumes of any investment in order to make a difference to their portfolios. To do so without disturbing the market requires the use of off-market trading facilities but the EU’s double volume caps were designed to limit off-market transactions. (It is probable that these very large funds championed the removal of the Double Volume Caps in the UK, hence the FCAs swift response.)

Similarly, MiFID II ‘Best Execution’ aka regulatory technical standards RTS 27 and 28 were removed in December 2021, as the cost of producing these reports was far greater than any perceived improvement in transaction execution. Also in March 2022, the FCA removed the requirement to pay for research on companies with market capitalisations below £200 million as well as from research on fixed income, currency and commodity instruments.[ix]

But other reforms such as changes to short selling or unbundled research on larger companies were much slower in coming. Even The Edinburgh Reforms heralded with much fanfare last December were mostly prefaced with long-grass processes such as ‘consulting on removing’, or ‘intending to repeal’, or ‘launching a call for evidence on’, or ‘welcoming a PRA consultation on removing’, or ’establishing an accelerated taskforce‘, or ‘increase the pace of consolidation’ or ‘consulting on issuing new guidance’.[x] Exactly what these processes mean can be seen by what they have achieved – not very much.

Unbundled research payments have put UK asset managers at a disadvantage relative to US and other non-EU managers who do not have to pay for their research. UK asset managers investing outside the UK or EU also had to pay for international research typically provided as a bundled service with transaction fees by international broking firms.

Enforced unbundled research payments also limited the amount of research available on less traded companies as both independent research providers as well as the research departments of large investment banks moved to cover the most popular companies in order to attract the greatest number of customers for their efforts.

Short selling limits were introduced by the EU to protect their government debt and companies’ equity and debt values from market determined price discovery. The EU was never comfortable with the active markets of ‘Anglo-Saxon capitalism’, preferring long only investments for life, preferably with an EU government owning golden shares in the company to prevent takeover bids or activists’ shareholders gaining positions on company boards.

The UK Treasury ’s consultation regarding short selling of Sovereign Debt and Credit Default Swaps (CDS) closed in August this year, and they are still analysing the feedback. However, the government is proposing to remove restrictions on uncovered short positions in UK sovereign debt and CDS, remove the requirement to report sovereign debt and CDS positions to the FCA and amend the market maker and authorised primary dealer exemptions to reflect these changes.[xi] This is a welcome change as other jurisdictions, such as the US and Singapore, do not have restrictions on short selling sovereign debt and CDS.

But the FCA’s short selling regulations for equities still require notification when private net short positions reach 0.1% of the issued capital and notification when public share net short positions reach 0.5% of the issued capital. This information is published on the FCA website. The Treasury is planning to replace the public disclosure of the short positions of individual short positions with an aggregate short position for each issuer and to increase the private notification limit from 0.1% to 0.2%. For comparison the notification limit for a long equity position is 3.0%.[xii]

Short sellers keep company share prices honest and as the world is heading towards a period of lower growth and recessions being short equities may well be more profitable than being long. But public notification of short positions encourages individual investors to organise a ‘short squeeze’ with other investors via social media sites as happened with the GameStop short squeeze in 2021 organised on Reddit.

The Treasury’s plan for building a smarter financial service regulatory framework was published in July this year, three and a half years after the UK left the EU. It contains a grid of seventeen EU regulations with proposed changes most of which will be changed by Statutory Instrument at the end of 2023 or during 2024. The Statutory Instrument making changes to the Short Selling Regulations are tabled to be put before parliament in 2024.

But the lack of change can’t be completely blamed on the Treasury and the FCA. In the FCA’s Call for Evidence regarding short selling, the FCA only received 20 responses from industry professionals such as banks, fund managers, market makers and trading venues, even though the FCA regulates 51,000 businesses in the UK. They also received five responses from think tanks and 831 responses from retail investors who may well have had the most influence on the eventual outcome. If City participants don’t participate in the process, the financial service industry will get the regulatory changes they deserve.

Productivity

Many politicians and economists like to blame low productivity for all of the UK’s ills and most of them will assume that low productivity is the use of labourers on a construction site or in a factory rather than a machine. And while this is a good example, our service industries’ productivity, and consequently its profitability, is hampered by the government’s desire to make investments risk free. By trying to protect people, banks and companies from bad business decisions, the government has also greatly increased the number of cost centre staff dealing with risk and compliance in most industries.

It is difficult for a service industry to improve its productivity if a large proportion of its staff are employed to complete mandatory regulatory compliance. By saving ‘too big to fail’ companies and by trying to protect individual investors from their bad decisions, governments have introduced too much regulation.

The best way to protect companies and investors is to make them aware that no one will save them. Companies and individuals need to take responsibility for monitoring and limiting their own risks. Private investors need to revert to buyer beware attitudes – if something sounds too good to be true, or even if it sounds like a sensible protection, potential investors or purchasers should still research the costs and the returns and whether they are already paying for the same service. Financial education in schools would also be helpful and possibly more use than forcing everyone, including the innumerate, to study maths. Companies need to monitor, measure and limit their own risk taking to amounts they can afford to lose and have reserves for such an occasion.

Mandatory compliance now includes Anti Bribery and Corruption compliance, Anti-Financial Crime compliance, Anti-Money Laundering compliance, Combating the Financing of Terrorism compliance, as well as compliance with international embargos and sanctions. Additionally, investment bank risk management can cover credit risks, non-financial risks, liability risks, operations risks and portfolio risks. All of these compliance and risk department silos are cost centres that must be paid for out of a firm’s revenues. And they are additional to the regular fixed costs of running any business: management, accounting, legal, and human resources.

Meritocracy and staff selection

The most important element of any successful service industry is its staff. They are any City firm’s greatest asset and are consequently well renumerated if they are successful and quickly fired if they are not. But it is important that firms can hire the best person for the job, based on performance, experience and skills and not be coerced into employing staff, choose board members or hand out senior board positions based on ethnicity, gender, religion, or any other diversity and inclusion category.

The fastest growing companies in the world in the last decade have been: Facebook (Meta), Amazon, Tesla, Apple, Netflix and Google (Alphabet). What is interesting about this group is that none of them have a female founder nor do they now have female CEOs, although Tesla has a female Chairwoman, Robin Denholm, and Google and Meta have female CFOs, Ruth Porat and Susan Li. But I very much doubt that either Denholm, Porat or Li were promoted to their positions as part of a government-imposed box ticking exercise. What is also obvious is that investors have been happy to invest in these companies regardless of the gender or ethnic diversity of their boards.

Yet the UK’s FCA now requires listed companies to disclose in their annual financial reports (on a comply or explain basis) the percentage of women on their boards – the FCA’s target is at least 40% of board members with a woman in at least one of the senior board positions (Chair, CEO, CFO or Senior Independent Director). The FCA also requires at least one member of the Board to be from a non-white ethnic minority and that companies include a numerical table on the diversity of their board and executive management by gender and ethnicity.[xiii]

This is additional to UK mandatory annual reporting requirements on diversity policies and gender pay gap reporting and the voluntary DEI data collect undertaken by companies to ensure they comply with the Equality Act 2010 which provides legal protection from discrimination due to: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation.

However, many company Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) policies go beyond legal compliance by seeking equality of outcomes for all employees for other characteristics including: accent, age, caring responsibilities, colour, culture, visible and invisible disability, gender identity and expression, mental health, neurodiversity, physical appearance, political opinion, pregnancy and maternity/paternity and family status and socio-economic circumstances amongst other personal characteristics and experiences.[xiv]

Although the US has had Equal Employment Opportunity laws since the 1960s, the New York Stock Exchange has no such DEI board requirements for listed companies. While Nasdaq listing rules only require only 2 diverse company directors: one woman and one from an ethnic or LGBTQ+ minority group.[xv] However Foreign issuers on Nasdaq and SMEs are not required to have an ethnic minority board member and companies with five or fewer directors only need to have one diverse director. Although like the UK, Nasdaq also requires a Board Diversity table, by gender and ethnicity, to be published by listed companies before its annual meeting.

Interestingly the Singapore Exchange requires listed companies to maintain a board diversity policy based on gender, skills and experience[xvi].[xvii] The Singapore Exchange also requires companies to explain how their board’s skills, talents, experience and diversity serves the needs and plans of the issuer which should eliminate box ticking appointments.

If only the US and UK had a similar system to Singapore, then we might not have seen Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse because no one on their board or in their management team seemed to have any experience that even ‘safe’ government bond prices can go down as well as up – SVB collapsed after losing $2.25bn (£1.9bn) in US government bonds, whose price fell as the US money supply and interest rates increased.[xviii]

Meanwhile, Hong Kong has mandated that all listed company boards must have at least one woman director by 31 December 2024. Hong Kong will be the first exchange to make this mandatory, rather than simply use ‘comply or explain’ rules. While the National Stock Exchange of India requires its top 100 companies to have one independent female board member.[xix]

Unsurprisingly, searching for diversity and inclusion on the listing requirements of Nasdaq Dubai produces no results.

But are the UK’s DEI listing requirements even necessary and do they put the UK at a disadvantage in attracting new listings? Since the 1990s when many non-Anglo-Saxon countries opened their markets to international investors, financial service firms in the UK have employed staff from those countries, but not for DEI reasons. They were employed because they were exceptionally good at: selling, trading, structuring products, calculating risks, were fluent in languages or understood international economies or legal systems.

Female students are the majority in both undergraduate and master’s programs in UK universities and so are likely to make up the majority of candidates for jobs requiring such educational attainment. For what it’s worth, the recipient of the highest bonus payment in the 100+ dealing room where I worked in the early 1990s was a female, ethnic-minority immigrant. The old-school-tie English stockbrokers were taken over, or went out of business, many years ago.

But as City firms are already burdened with excessive regulations, to be adding requirements to employ staff of any reason other than merit, is an anathema. Investors are interested in advice, investment returns and custodian services not in the ethnicity or gender of a bank’s staff. The percentage of females working in a firm is not important, while the successful results of those women or men at investing, selling, managing, trading, clearing, accounting, consulting or whatever they are employed to do, is important.

As is the PRA and FCA’s proposal to remove the cap on bankers’ bonuses paid in 2025, based on their performance in 2024, and thus rewarding successful employees for their work regardless of their gender or ethnicity. Unfortunately, the FCA has implemented their MIFIDPRU renumeration regime for investments firms which is broadly similar to the EU’s Investment Firms Directive and Regulation and still very restrictive as to how UK investment firms can reward their staff as well as requiring firms to complete a MIFIDPRU renumeration report annually.[xx]

De-banking essential services

Despite evidence to the contrary, the de-banking of individuals is against the law in the UK. FCA Regulation 18 of the Payment Accounts Regulations 2019 forbids discrimination by a credit institution against consumers legally resident in the UK due to their nationality, place of residence or sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation when those consumers apply for or access a payment account. But while we have heard much in the press about how many UK banks seem to be breaking this regulation, the UK economy has an even greater problem as many banks and investment managers and insurance companies are de-banking our vital energy industry.

While Environment Social and Governance (ESG) commitments sounds like a good idea, many UK companies, banks, insurance companies and pension managers have found the easiest way to meet their ESG targets is to stop investing in extractive industries especially oil, gas and coal production.

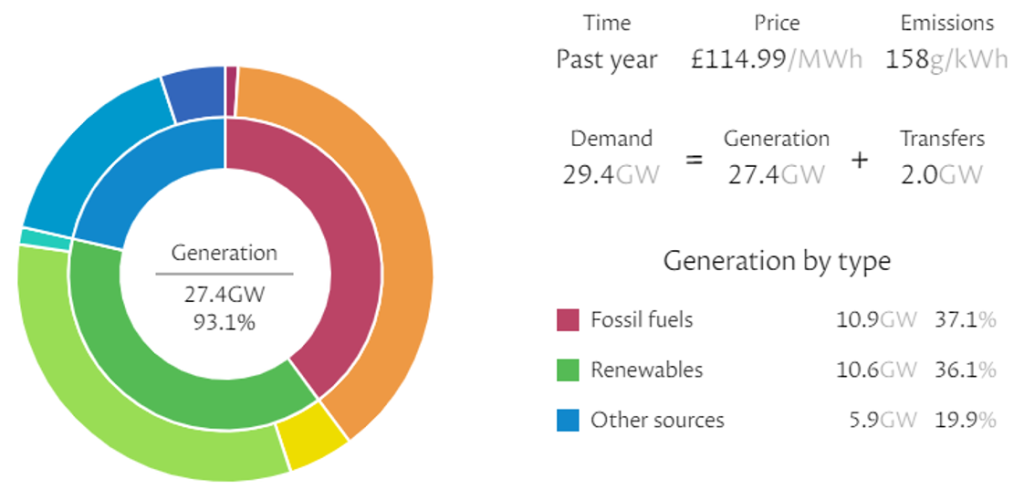

But the world, and especially the UK, still relies on oil, gas and coal to run our industrial transport – cargo ships, semi-trailers, trucks and vans, our personal travel – cars and trains, for heating our homes, for chemicals, plastics and cement production and most importantly for the production of 37% of the UK’s electricity.

This can be seen in the chart below of annual UK electricity production by type of generation. Whenever the wind drops, the UK’s gas and coal fired generators step in to keep our electric grid at 50hz, and whenever the wind is so strong that the turbines have to be turned off, again gas and coal fired turbines step in. And when the wind is not too weak or too strong, we turn down the gas generation. There is no viable alternative to this system. Nuclear power could provide the UK with constant low emission electricity, but it will be at least ten years before any new nuclear power, either large, medium or small modular reactors are available.

UK annual electricity generation by type, Oct 2022 to Sep 2023[xxi]

(Gas generation in Orange, Wind generation in light Green)

Banks, fund managers and insurance companies rely on electricity to run their dealing rooms, financial records and data storage servers. According to UK Energy Research Centre, the average UK data centre consumes half a million kilowatts of electricity per year, depending on the server’s configuration, location, cooling system and usage pattern. They estimate that running the estimated 80,000 data centres in the UK used over 11% of the UK’s total electricity generated in 2016.

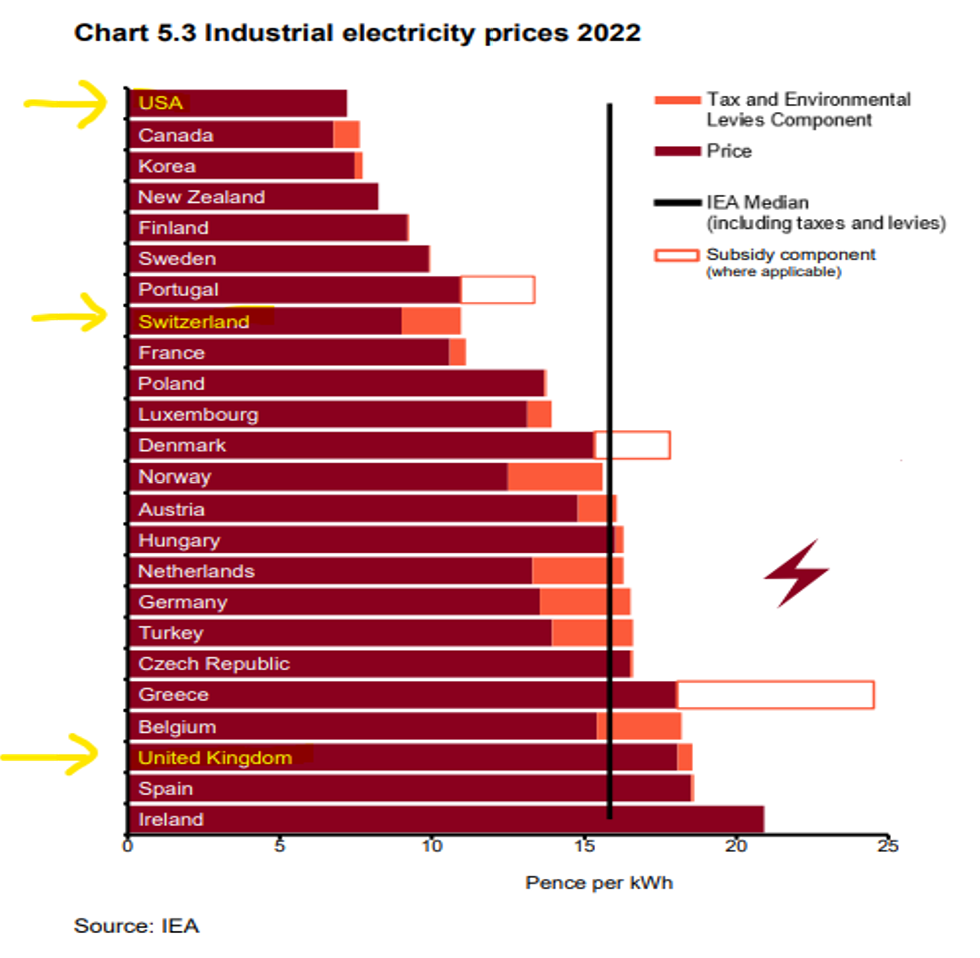

The UK already has some of the most expensive electricity in the developed world measure by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Of the 26 IEA countries reporting industrial electricity prices in 2022, the UK had the third highest priced electricity including taxes and levies with only Spain and Ireland having higher prices. The USA had the lowest industrial electricity prices, less than half that of the UK while another financial service rival, Switzerland’s industrial electricity is roughly three quarters of the UK price, as can be seen in the IEA’s chart below.[xxii]

Large international banks and insurance companies employ massive data servers, for example JPMorgan Chase’s data infrastructure contains over 450 Petabytes (1015 bytes) of data serving more than 6,500 applications 1. If the UK wants to remain a competitive place for financial services, then having very expensive electricity, not financing new UK oil and gas developments but instead relying on imported LNG from the US and Qatar – may not be our smartest move. Without reliable cheap electricity, most financial, insurance, pension and business service businesses would be out of business.

Climate related risk reporting requirements

All UK listed companies, banking and insurance companies (Public Interest Entities) [xxiii] and registered companies with more than 500 staff are required to disclose: their governance arrangements for assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities; a description of how they identify, assess, and manage climate related risks and opportunities; how these processes are integrated into their overall risk management processes; a description of the principal climate-related risks and opportunities they face and the time period over which those risks and opportunities are assessed; a description of the actual and potential impacts on their business model and strategy; mandatory climate-related financial disclosures, analysis of the resilience of their business model and strategy under different climate-related scenarios; a description of the targets used to manage climate-related risks and to realise climate-related opportunities and their performance against those targets; and the key performance indicators used to assess progress against those targets and a description of the calculations on which those key performance indicators are based.

These requirements are not unique to the UK but align with those issued by the international Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). And are designed to allow a user of a company’s accounts to understand how risks and opportunities relating to climate change are identified, considered, and managed within its governance structure and to understand the potential effect of that risk or opportunity on the business. The disclosures should explain the mitigations that a business has already put in place or is planning to take and the likely time periods over which the risk or opportunity is expected to crystallise.

Interestingly, the Government’s published guidance also requires the assessment of the appropriate time periods for short, medium and long-term risks and companies should take into account the nature of their business including budgetary cycle, asset lives, length of financing arrangements and the periods over which climate risks and opportunities are expected to affect the business.

Although this sounds sensible, according to the ONS, the average UK company lifespan is just 8.6 years. Even in the US, the average corporate lifespan of an S&P500 company is only 21 years, maybe companies should spend more time ensuring their businesses are successful and profitable rather than spending too much time worrying about how climate change will affect their businesses in 100 years’ time. After all, according to NASA global sea levels have only increased by 8 inches during the last 130 years[xxiv].

Conclusion

Financial, Insurance and Pensions and Other Business Services are now the UK’s largest export industry and could have a great future, but our regulators need to allow companies to concentrate on their core business functions, access their own risks and employ the staff they believe are most suited to their requirements especially as our service exports grow to countries with different customs, concerns and priorities. High taxes and low productivity, caused by over prescriptive regulations, listing requirements not followed by other countries, and disproportionate ESG reporting rules all coupled with very expensive electricity could easily destroy this thriving sector of the UK economy.

[i] UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

[ii] AstraZeneca CEO says pharma giant chose Republic over UK because of tax rates and green energy | Business Post

[iii] GFCI 34 Rank – Long Finance

[iv] Corporation Tax rates and allowances – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[v] Corporate Tax Rate By State [2023] – Zippia

[vi] Corporate Tax Rates 2023 (deloitte.com)

[vii] The State’s top 10 corporate taxpayers: who are they? – The Irish Times

[viii] Top ten corporation tax payers paid 53% of 2021 total (rte.ie)

[ix] PS21/20: Changes to UK MIFID’s conduct and organisation requirements (fca.org.uk)

[x] Financial Services: The Edinburgh Reforms – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[xi] Short_Selling_Regulation_Review_-_sovereign_debt_and_CDS_consultation_document__1_.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[xiii] PS22/3: Diversity and inclusion on company boards and executive management (fca.org.uk)

[xiv] Equality, diversity and inclusion in the Workplace | Factsheets | CIPD

[xv] SEC Adopts Nasdaq Rules on Board Diversity (harvard.edu)

[xvi] 710A | Rulebook (sgx.com)

[xvii] Board Diversity Disclosure – Council for Board Diversity

[xviii] Silicon Valley Bank: Regulators take over as failure raises fears – BBC News

[xix] National Stock Exchange of India | Sustainable Stock Exchanges (sseinitiative.org)

[xx] MIFIDPRU Remuneration Code (SYSC 19G) | FCA

[xxi] National Grid: Live (iamkate.com)

[xxii] Quarterly Energy Prices September 2023 (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[xxiii] *Mandatory climate-related financial disclosures by publicly quoted companies, large private companies and LLPs (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[xxiv] Sea level rise: Global warming’s yardstick – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet (nasa.gov)