Making financial decisions for young people who lack capacity: A toolkit for parents and carers

Introduction

As a parent or carer, supporting a young person who lacks capacity to make financial decisions may be challenging. In particular, once a young person enters adulthood, you must decide if it is appropriate for you to continue to make financial decisions on their behalf, and follow the rules in place to allow you to do so.

This toolkit is a guide for parents and carers to make financial decisions on behalf of young people from ages 16 to 25 who may lack the mental capacity to make decisions for themselves. It aims to explain the principles of decision making and the processes in place to make financial decisions on a young person’s behalf. These processes exist to protect young people and their money, as well as to help you empower them to make their own decisions about their finances, where possible.

By the end of this toolkit, you should be able to understand:

- what lacking mental capacity means and the decision-making principles

- the changes to decision-making when a child reaches adulthood

- the relevant route for you to make financial decisions on behalf of a young person, including how to access a Child Trust Fund

- if the young person is under the age of 18, how to prepare to make financial decisions when they reach adulthood

When a child or young person transitions to adulthood, new principles also apply to health and welfare decisions , including making decisions about care, made on their behalf.

Advice on making health decisions for people who lack mental capacity can be found on the GOV.UK website. At the end of this toolkit, there is a glossary explaining key terms you may encounter in this toolkit.

Mental capacity

Mental capacity

Mental capacity refers to the ability for a person to make a decision for themselves at the time it needs to be made.

Lacking mental capacity

When a person lacks mental capacity, they do not have the ability to make a particular decision for themselves at the time it needs to be made. This might be due to disability, disease or injury.

The ability to make a decision may change depending on the decision that needs to be made. For example, a young person could have the ability to make a decision about what they want to eat, but not what they want to wear.

Fluctuating capacity

The ability to make decisions can also change depending on when the decision needs to be made. This means that some people may lack capacity at some times, but not at others.

For example, a young person may have the capacity to decide what they want for breakfast one day, but not the next.

This is known as ‘fluctuating capacity’.

This may be because of an illness or condition which changes their capacity.

A young person may have fluctuating capacity at a particular time if they have, for example:

- a brain disorder

- a psychological illness

- a memory disorder such as childhood dementia

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA)

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) applies to everyone over 16 years old who lives in England and Wales and lacks the capacity to make some or all of their own decisions.

The purpose of the MCA is to empower people to make their own decisions wherever possible. Where this is not possible, the MCA outlines how to allow others to make decisions on behalf of someone that lacks capacity whilst protecting their rights and interests.

The Five Principles

The MCA sets out 5 clear rules you must follow to support a young person aged 16 and over who lacks the capacity to make their own decisions. These rules are called the 5 statutory principles.

Principle 1: Assume capacity

‘A person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that he lacks capacity.’

Everyone has the right to make their own decisions. You should not make a decision on behalf of a young person, unless you can show that they cannot make the decision.

Principle 2: Supported decision making

‘A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him to do so have been taken without success.’

This means that parents and carers should support a young person to make their own decisions wherever possible, before making the decision for them.

To support someone to make a decision you should ensure that:

- they have the relevant information to make the decision in an accessible form

- they are made to feel at ease

- anyone else who could support them to make a decision is available

People providing support should not put undue pressure on a person to make a particular decision, so you should be careful not to try to persuade the person what to do.

Principle 3: Unwise decisions

‘A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because he make an unwise decision.’

If a young person makes an unwise decision that you as a parent or carer are unhappy with, you should not automatically take over the decision for them.

Everybody has their own values, beliefs, preferences, and attitudes which may lead them to make a decision another person might not have made.

However, you may need to think more carefully about their decision-making capacity if they:

- make repeated unwise decisions that puts them at risk of harm, or

- make a particular unwise decision that is out of character

Principle 4: Best interests

‘An act done, or decision made, under this Act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in their best interests.’

As someone acting on behalf of a person who lacks mental capacity, you must ensure that every act or decision you are taking on their behalf is in their best interests, rather than in the interests of you or anybody else.

Particularly, as a parent or carer this might mean considering:

- a young person’s past and present wishes and feelings.

- any professionals involved in their care.

Who should be involved?

- Take every effort to enable and encourage the person to take part in making their own decision

- Consider the views of other people who are close to the person who lacks capacity, including for their views of what that person wanted

What information should I consider?

- The circumstances of the situation

- The person’s past and present wishes and feelings, beliefs, values and any relevant cultural factors

- The person’s capacity and if they will regain capacity to make a particular decision, delaying a non-urgent decision

Do not use someone’s age, gender, appearance, condition or behaviour to work out their best interests.

Principle 5: The less restrictive option

‘Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action.’

This means that before you act or make a decision on behalf of a young person, you should stop and think about whether you can achieve the same outcome with a different decision or action, that effects the person’s rights and freedoms less. In practice, you should stop and consider what you want to do, and whether you can do it in a way that affects the young person less.

What changes when a child transitions to adulthood at the age of 18?

When a child in your care starts to transition to adulthood, your parental responsibility to make decisions on their behalf will start to change. New decision-making rules will start to apply, which you will need to consider before making decisions for them.

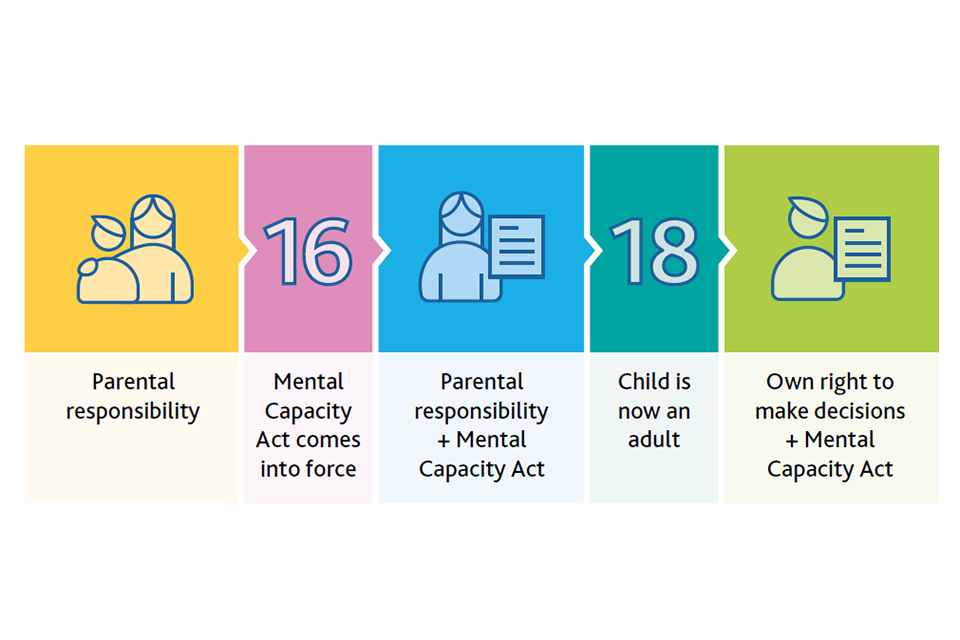

From the age of 16

When a young person reaches the age of 16, the MCA framework will begin to apply to them. Until the age of 18, you will also retain parental responsibility to make decisions for them. Precisely how the MCA and parental responsibility interacts can be complicated, but the best approach is for you to now proceed as if the MCA applies in all cases of decision making on behalf of your young person. As a result, before making a financial decision on your young person’s behalf, you should take steps to support them to make their own decision. If they cannot make their own decision, the decisions you make for them about their finances must be in their best interests.

From the age of 18

Once they turn 18, a young person legally becomes an adult. This means that in law they have the responsibility to make their own decisions. This means that no one else has the right to make decisions for them.

At this time, you will no longer have parental responsibility to make decisions for them. However your views should still be considered when others are making decisions on behalf of the young adult you care for to help work out the best interests.

To make a decision on the behalf of someone who has turned 18, you must seek their consent and apply the principles of the MCA. If they lack the capacity to provide consent, you must obtain the relevant legal authority to make the financial decision for them.

In particular, you will have to obtain legal authority to make financial management decisions involving another adult’s property and assets, for instance savings in a bank account. This is a principle of common law which applies even if you are the person’s:

- parent (including if you have made contributions to assets or property) or

- next of kin, spouse, or family member

As a result, if a young adult lacks capacity to access their bank accounts or their own property, you must seek proper legal authority to access them on their behalf.

Myth

Parents and carers have the right to access their adult child’s bank accounts.

Fact

No individual has the automatic right to access the accounts or property of another adult, including if that person is a parent who contributed large sums to their child’s account.

Managing state benefits

If a young adult lacks capacity, and their only form of income is state benefits, including Personal Independent Payments, an individual, including their parents or carers, or a corporate body can apply to the DWP to become an appointee to manage the benefit on their behalf. This is an individual that has the responsibility to manage the benefit on the young person’s behalf. Any decision an appointee makes when using the benefit should be in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity.

A timeline showing the changes in decision-making responsibility as a child transitions to adulthood. When a child turns 16, the MCA applies to them and when they turn 18 and become an adult they have the legal right to make their own decisions.

Myth

As an appointee who receives a young person’s PIP into their own bank account, it also means that I have authority to access the young person’s own bank account.

Fact

An appointee does not have the authority to access a young adult’s assets, such as savings in their back account. To access such an account a separate legal authority would be needed, for example a Power of Attorney or deputyship order.

Obtaining legal authority

Summary

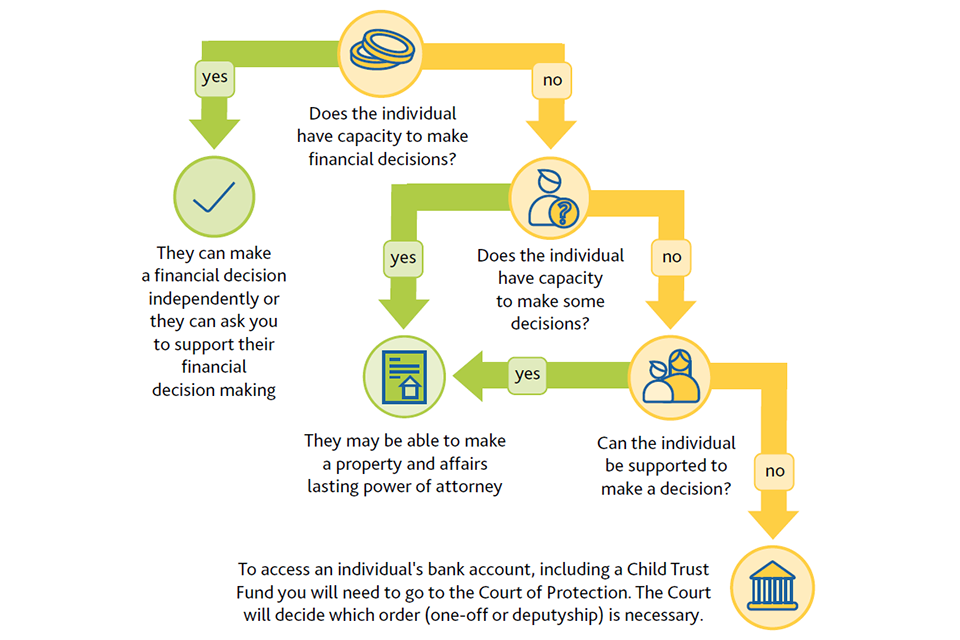

The MCA sets out 2 routes to grant someone legal authority. The type of legal authority you need to make financial decisions for a young adult depends on their capacity.

You will also need legal authority to make a health decision on behalf of an adult, which can be sought through the same routes. For more guidance on obtaining legal authority for health decisions please visit https://www.gov.uk/make-decisions-for-someone.

Making financial decisions where someone may lack capacity, including accessing a Child Trust Fund

A tree diagraph with the different pathways to obtain legal authority. If someone has the capacity to they can make a lasting power of attorney to allow others to make financial decisions on their behalf. If someone lacks mental capacity, their parent and carers will have to apply to make finance decisions on behalf their behalf including to access a Child Trust Fund.

Each of these pathways will be explained in more detail below.

Does the young person have capacity to make decisions for themselves?

If a young adult has capacity to do so, they may wish to make a property and affairs lasting power of attorney (LPA) to allow someone (called the ‘attorney’) they trust to make financial decisions on their behalf should they lose capacity.

An LPA must be made by a person (called the ‘donor’) when they have capacity to do so. This could include even when they do not have capacity to make every decision about their property and affairs. Making it must be the donor’s choice.

The donor can also provide specific directions about the decisions they want the attorney to make when they want an attorney to act on their behalf, for example, whilst they still have capacity or only when they have lost capacity.

A property and affairs LPA could allow an attorney to:

- manage a bank or building society account

- pay bills

- collect benefits or a pension

- sell the person’s home

- make or manage investments

While acting on behalf of a donor to manage their property and affairs, an attorney must follow the principles of the MCA. As a result, if you act as a young adult’s attorney, you must assume that they have the capacity to make decisions about their finances. If they struggle to make a decision for themselves, you should try to support them and only act on their behalf when they are unable to do so, even with support. In practice, this might mean that a young adult continues to organise their daily expenditure, whilst you use an LPA to manage their more complex finances. Any decision made on behalf of the donor must be made in their best interests.

A property and affairs attorney also has a wider set of responsibilities when acting on behalf of a donor, such as keeping accounts of spending. You can find these in Chapter 7 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

How to prepare

A person must be 18 years old to make an LPA. However, to ensure that a property and affairs LPA is in place when needed, you can discuss with your young person the choice to make an LPA and support them to start the paperwork before they turn 18 so that it is ready to sign when they turn 18. The LPA will then need to be registered with an organisation called the Office of the Public Guardian before it can be used.

We strongly recommend that if a young adult chooses to, and they have the capacity to do so, they create a property and affairs LPA to avoid their parents and carers from applying to the Court of Protection to get authority to manage their finances if they lose capacity.

How to make and register an LPA

- The donor must choose their attorney (they can have more than one)

- The donor must decide if they want to put any limitations (called preferences and instructions) on the powers they wish to give their attorney

- The relevant forms to make a lasting power of attorney must be filled in to reflect the decisions made

- The completed LPA forms must be sent to the Office of the Public Guardian to be registered

Registration fees apply when making an LPA. Fee exemptions are available for those who are on low income or receive certain benefits. Please visit GOV.UK to apply for a reduced fee for your power of attorney fees.

Does the young person lack capacity to make financial decisions for themselves?

If a young adult lacks capacity to make decisions for themselves, and no LPA has been created, an order from the Court of Protection, one-off or deputyship, is needed to manage their property or accounts on their behalf.

The Court of Protection

The Court of Protection (CoP) makes decisions regarding people who may lack capacity. The Court exists to protect vulnerable people who lack mental capacity and their best interests, which might include choosing trusted individuals to make decisions on their behalf.

Myth

I will have to go to the Court in person to make application for a Court of Protection order.

Fact

The Court of Protection makes most of its decisions on paper, so you may not ever need to go to court and appear in front of the judge. Often you can make an order to the Court through a single application.

Myth

I will need a lawyer to help me with my application to the Court.

Fact

You do not need a legal representative when applying to the Court of Protection, although some individuals may choose to use a lawyer to help them fill out the forms.

When making an order the Court may ask lots of questions. This is so that it has the relevant information to ensure that it can make a decision in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity.

Myth

The Court of Protection order application is confusing, and it takes a long time to receive an order.

Fact

The Court has been simplifying its forms and using new online application tools to make it quicker and easier to receive an order. You can also now fill out the forms online.

Property and affairs one-off order

If you need to make a specific decision about a young adult’s finances, then you can apply to the Court for a one-off order. A one-off order gives someone the legal authority to make a specific decision in the best interests of a person that lacks capacity.

You may use a one-off order to:

- access money earmarked for a specific need such as wheelchair or caring equipment

- sell a young adult’s property

Property and affairs deputyship

Sometimes it is not practical for the Court to make a single order if they think that somebody may need to make future or ongoing decisions on behalf of someone who lacks capacity. The Court will make the decision as to who to appoint in the best interests of the person, taking into account who they would want to be appointed.

A property and affairs deputy can make any financial decision the Court appoints them to make in the best interests of a person who lacks mental capacity. However, the Court will ensure that the deputy’s power is as limited in time and scope as possible.

The Court decides who can be a deputy, which is often the person’s family, carers, or friends.

How to prepare

If you believe that a child or young person in your care will lack capacity to make financial decisions for themselves in the future, we advise that you start to familiarise yourself with the Court of Protection processes as soon as possible.

You can make an application to the Court of Protection when a young person is under the age of 18, if you believe your young person will lack capacity to make decisions for themselves when they turn 18. This will ensure that you have the proper legal authority to make financial decisions for them when they reach adulthood.

Applying for a property and affairs order

The application process for a one-off or property and affairs deputyship order is the same, and the Court of Protection will decide which type of order you need.

To apply for a property and affairs order you must:

- Speak to the person you’re applying to the Court of Protection for

- Notify at least 3 people connected to the person in the application

- Complete the relevant court forms for a property and affairs order

- Submit the forms online or by post to the Court of Protection

There are fees for court orders, and for applying for a deputyship, although it is possible for you to pay a reduced fee or no fee at all in some cases. Apply for fee reductions or waivers.

For health decisions, you should explore making a Court of Protection personal welfare application.

What happens in an emergency?

If you need to gain emergency access to the finances or property of a young adult, then you can apply for an Emergency Interim Order from the Court.

An Emergency Interim Order can give you access to an account or property in as little as 24 hours. However, the Court will determine whether the need is urgent.

You can apply to make an urgent or emergency application to the Court of Protection.

Do you want to access a Child Trust Fund?

A Child Trust Fund (CTF) is a type of tax-free savings account given to every child born between 2002 and 2011, as a part of a government scheme to help children arrive at adulthood with savings. A CTF matures when the account holder turns 18. A CTF is an asset. Therefore, anyone wanting to access a matured CTF must have the proper legal authority.

If they have the capacity to do so, a young adult can choose to make an LPA to give someone they trust the legal authority to access their CTF.

If a young person lacks capacity, their family or carers will need to apply to the Court of Protection for an order following the steps above. The Court will decide which type of order is necessary and in the best interests of the account holder.

If you believe that a young person in your care will lack capacity when they reach adulthood, in good time before they turn 18 you should put in an application for a court order. This means that when the young person turns 18, the order will be ready and you will be able to access the matured CTF.

If you are trying to access a CTF on behalf of a young person, it is likely you will not have to pay fees if you:

- apply before their 18th birthday

- ask for a fee waiver through the government Help with Fees scheme; or

- ask for a fee waiver due to exceptional circumstances

To note: If you are an appointee this does not allow you to access a CTF.

Summary

This toolkit has explained the principles of decision making to support a young person who lacks capacity in managing their financial decisions.

As a parent or carer, to make financial decisions on a young person’s behalf whilst protecting their best interests, you should now:

Follow the route relevant to you if you need to make a financial decision on behalf of a young person.

If they have capacity:

- Support them to make decisions, where necessary

- They may choose to make an LPA

If they lack capacity:

- Make an application to the Court of Protection

Or if the young person is under the age of 18, start putting preparations in place to make financial decisions when they reach adulthood.

Additional resources

If you need further support on how to make decisions on behalf of someone who lacks mental capacity, please see the following resources from our partner SCIE:

Glossary of terms

| Appointee | A person or corporate body appointed by the DWP to claim and collect social benefits or pensions on behalf of a person who lacks capacity to manage their own benefits. An appointee is permitted to use the money claimed to meet the person’s needs. |

|---|---|

| Attorney | Someone appointed under a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) who has the legal right to make decisions within the scope of their authority on behalf of the person (the donor) who made the LPA. |

| Carer | Someone who provides unpaid care by looking after a child or young person who needs support because of sickness, age or disability. In this document, the role of the carer is different from the role of a professional care worker. |

| Child | Someone who has not yet reached their 18th birthday. This is in line with the law of England and Wales, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. |

| Child Trust Funds (CTFs) | CTFs are long-term tax-free children’s saving accounts set up by the Government in 2002 to help children arrive at adulthood (age 18) with savings. The first CTFs matured in September 2020, when the oldest account holders turned 18. The last CTF will mature in 2029. |

| Common Law | In England and Wales, common law is the law derived from custom and legal precedent, including from judges sitting in court. Court of Protection (CoP).

The CoP is the specialist court which deals with decisions regarding people who may lack capacity. This could include making judgments on whether an individual has capacity. |

| Deputy | Someone appointed by the Court of Protection with ongoing legal authority as prescribed by the Court to make decisions on behalf of a person who lacks capacity to make a particular decision. |

| Donor | A person who makes a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). Only the donor can make decisions about their LPA. A donor must be at least 18 years old and have mental capacity when they make their LPA. |

| Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) | An LPA is a legal document. It lets the donor choose trusted people who will be able to help them make decisions if the donor ever wants or needs them to.

There are 2 types of LPA: • health and welfare An LPA must be registered by the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) before it can be used. |

| Legal authority | Legal authority is the official permission or right to act, in this context on behalf of another person. |

| Mental capacity | Mental capacity is the ability to make a specific decision at a specific time. For example, this includes the ability to make a decision that affects daily life – such as whether to buy groceries – as well as more infrequent or significant decisions. It also refers to a person’s ability to make a decision that may have legal consequences for them or others, for example a decision about whether to sell property they own. A person may have capacity for some decisions but not others, and their capacity may change (fluctuate) over time. |

| The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) | The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 is the key legal framework to empower, support and protect vulnerable people who may not be able to make decisions for themselves because of disability, injury or illness. |

| Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) | OPG is the agency in England and Wales that supports individuals who may lack capacity or who are planning for a time when they may lack capacity. OPG’s responsibilities include registering LPAs, investigating where an attorney may have misused an LPA and supervising deputies and guardians appointed by the Court of Protection. |

| Parental Responsibility | The legal rights, duties, powers and responsibilities that a parent of a child has by law. |

| The Statutory Principles | The Statutory Principles of the Mental Capacity Act. They are designed to emphasise the fundamental concepts and core values of the Act and to provide a benchmark to guide decision makers, professionals and carers acting under the Act’s provisions. The principles generally apply to all actions and decisions taken under the Act. |

| Young Adult | In this document we define a young adult as someone from the ages of 18-25. A person is only defined as an adult once they are legally over the age of 18. |

| Young Person | In this document we define a young person as someone from ages 16-25. The MCA framework will begin to apply to a person from age 16. |