Nearly half of UK vice-chancellors expect their university to be in financial deficit this year, nearly all expect some institutions to breach agreements with banks, while almost none expect government to support a provider in serious financial trouble, with one leader fearing ministers are “determined to drive us out of business”, according to a Times Higher Education survey.

As UK universities fear a domestic funding crisis combined with a fall in financially vital international recruitment amid the government’s tightening of visa policy, THE asked campus heads for their views on sector finances, with 51 responding.

One university leader, who chose to remain anonymous, said given that research and the teaching of home students relied on cross-subsidy from overseas fees, “the government’s recent attitude to international students has been hugely damaging” and “it would appear that the government is determined to drive us out of business”.

Another said that uncertainty across the sector was “at unprecedented levels”, with reduced public funding, inflation and “the government’s hostile approach to our international students” providing “for a perfect storm, which will undoubtedly see a number of universities fail their ‘going concern’ requirements in the near future”.

Meanwhile, Rama Thirunamachandran, vice-chancellor of Canterbury Christ Church University, said in the survey: “The current HE funding model in England is broken and there is a need for a radical rethink.”

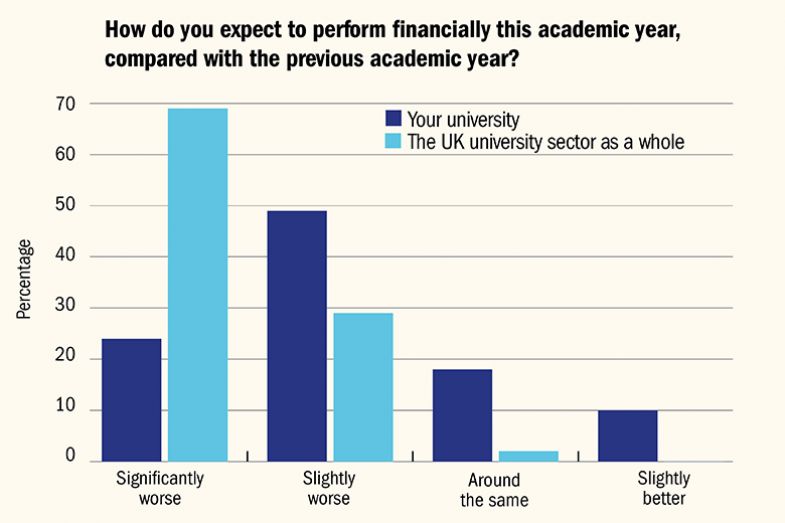

In the survey, asked how they expected their university to perform financially this year compared with last, 73 per cent of vice-chancellors responding said “slightly worse” or “significantly worse”.

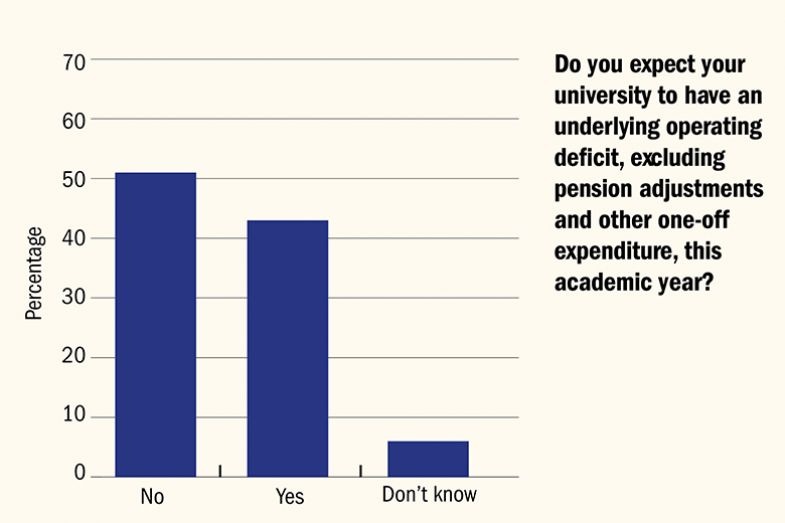

Forty-three per cent said they expected their university would record an operating deficit in the current financial year.

Six per cent of respondents expected their university to be at risk of breaching banking covenants this financial year – potentially jeopardising its ability to continue as a going concern, a key issue already facing some university governing bodies.

Asked about the sector as a whole, respondents took an even gloomier view. Ninety-eight per cent said they expected financial performance to be worse, and 94 per cent expected some universities to be at risk of breaching banking covenants.

However, asked about their level of confidence that the government would step in to support a university that got into serious financial trouble, 86 per cent of vice-chancellors responding were “not confident” or “not at all confident”.

In England, tuition fees were trebled to £9,000 in 2012. The fee cap was lifted to £9,250 in 2017, but the government has chosen to freeze it until at least 2025, by which time inflation will have eroded its value to £6,600 in 2012-13 prices, Universities UK (UUK) has estimated. Universities in Scotland recently suffered another cut in their funding from the Holyrood government, while universities in Wales and Northern Ireland also face domestic funding squeezes.

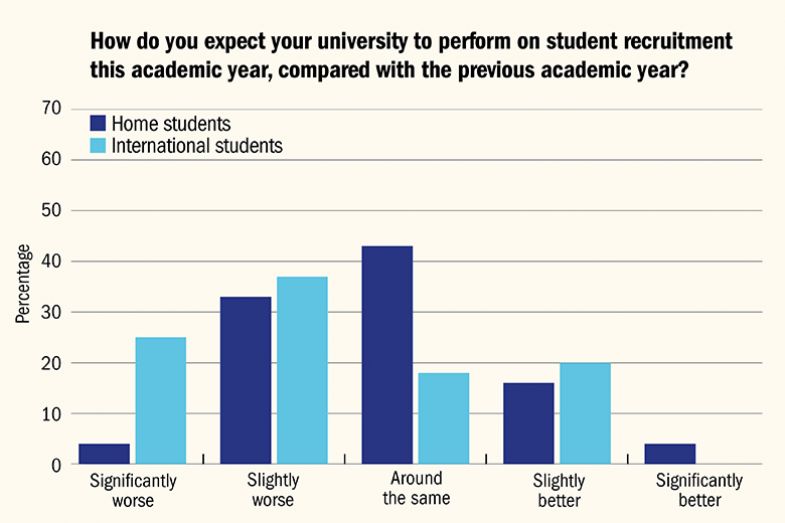

Among responding vice-chancellors, 20 per cent said they expected to do better on domestic recruitment this year, but 37 per cent expected to do worse.

Fears over international recruitment that has traditionally provided subsidy against falling domestic funding – deepened by the government having tightened visa rules on overseas students’ dependants and by its review of the graduate visa route – apply across the UK, as do worries about inflation and rising energy and pension costs.

Sixty-two per cent of respondents said they expected their international recruitment to decline this year – 25 per cent “significantly” – compared with 38 per cent who expected to hold steady or improve.

Modelling carried out by PwC for UUK and published last week warned that a five-percentage-point fall in international student income would leave half of universities in deficit, while a 20-percentage-point fall would leave four-fifths in the red.

From a list of key issues, vice-chancellors rated the failure of government to address real-terms reductions in per-student funding as the biggest worry, with 78 per cent “very concerned”. Rising staff costs were another key pressure point, with half of respondents either slightly or very concerned.

Asked to select options from a list of actions to improve financial performance, 27 per cent said their university was considering reducing the number of staff it employed, 29 per cent said it was considering other staffing cost reductions, 23 per cent said it was considering increasing staff-student ratios, while 4 per cent said it was considering reducing research activity.

On the question of which funding policy reforms they would support, the highest levels of support were for an increase in public funding, backed by 92 per cent of respondents. Seventy-three per cent of respondents said they would support an increase in tuition fees. Fifty-nine per cent said that they would support a switch to funding universities via a graduate tax.

Nick Braisby, vice-chancellor of Buckinghamshire New University, told the survey: “The current financial model for UK higher education is unsustainable and is placing at risk the enviable world-class reputation of UK universities. Universities are imaginative, innovative and adaptable and will work with government to drive productivity and economic growth in new ways, meeting the skills needs of the UK in the 21st century and extending the country’s global influence. But universities have to be supported by additional funding through a long-term and sustainable model that recognises their value to the public and society.”

Helen Langton, vice-chancellor of the University of Suffolk, said: “The sector is hurtling towards an unsustainable position financially, with more and more [institutions] fishing in the same applicant pots, be it undergraduate, postgraduate, home, international, apprenticeships, private partnerships, and so on, which has not been the case previously. I am not in favour of putting up fees for students to pay or incur loans for, but we cannot continue being so underfunded for much longer. A new model is clearly needed.”

Warning signs in university balance sheets

UK universities’ annual accounts indicate that institutions’ financial performance is already going in reverse.

Significant shifts in the valuation of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) pension fund continue to cause many universities to oscillate wildly from deficit to surplus each year. But a Times Higher Education analysis of 115 financial accounts for 2022-23 released to date instead focuses on the net cash in/out flow from operating activities – a figure that seeks to strip away the effects of financing and other items.

Though not perfect, it is viewed by experts as a key metric to determine how much cash a university is generating from its core business activities. And the analysis suggests that the sector’s finances are already heading in the wrong direction.

The core businesses of the 115 institutions produced £2.7 billion in net cash last year, which was down 42 per cent from £4.5 billion in 2021-22.

Of them, 91 (80 per cent) generated less cash from their operating activities after taxation in 2022-23 than they did the year before.

Bob Rabone, a former chair of the British Universities Finance Directors Group, said this was “clearly indicative of the huge financial pressure in the year”, arising from responding to inflation by increased staff costs and the continuing constraints on home student fee levels.

“In some cases, these pressures are relieved by increased student recruitment – but, where they are not, the need for remedial action to improve the financial position has become urgent,” he said.

Mr Rabone said it was typically rare that a university would produce a negative flow of cash, which would mean “a very tough situation” where a university’s operating activities were consuming cash.

However, that was the case for five of these institutions in 2021-22, and nine last year – including The Open University (down £66.7 million), the University of Surrey (£8.6 million) and the University of the Highlands and Islands (£6.8 million).

The Open University and Bishop Grosseteste University were the only two providers in the sample with net cash outflows in successive years.

Meanwhile, the University of Oxford had a net cash outflow of £3.1 million last year, which was the largest year-on-year fall of all 115 institutions – from an inflow of £191.5 million in 2021-22.

In its statements, the university said the reduction was explained by working capital movements, adding: “The 2021-22 operating cash flow benefited from significant increases in trade payables, research grant creditors and accruals over the year, whereas these all declined in 2022-23.”

Net cash flow from operating activities adjusts the surplus or deficit for the year for non-cash items such as pension provisions, depreciation and movements in debtors, creditors and similar items, as well as investing and financing activities, including investment and endowment income and capital grant income.

THE analysis shows that 21 per cent of the institutions reported a deficit for the year in 2022-23, compared with 68 per cent in 2021-22 and 31 per cent in 2020-21.

Of the 23 providers to record a deficit, the University of Central Lancashire’s was the largest, at £78 million, though it said its agreed deficit budget was “cash generative and again reflected responsible financial stewardship”.

Max Lu, vice-chancellor of Surrey, which reported a £22.4 million deficit, said it had been a “challenging year financially” given the pressures and constraints of rising inflation, with student recruitment particularly challenging in a competitive market.

“Persistent high inflation and cost-of-living pressures contributed to a financial deficit in 2022-23, so we need to be prudent to enable a planned return to surplus in 2024-25,” he wrote in the accounts.

And the University of Wolverhampton said its deficit of £11.9 million was a £15.9 million improvement on 2021-22, in line with the university’s financial plan, and was a result of a successful transformation programme.

“The impact of the continuing evolution of government policy towards higher education leads to uncertainty, and the university will need to continue to respond flexibly to the demands placed on it,” the board of governors said in a statement.

Mr Rabone said the reporting of surplus and deficit figures masked the underlying financial pressures on universities in the last year. And he added that it was vital to consider each university’s financial statement before drawing a partial or wrong conclusion of their real financial performance.

Patrick Jack