There is a hidden threat to the U.S. government’s finances, one that is rarely talked about in the open, and one that Congress does not seem to want to do anything about. It is a threat that emanates from the financial markets.

No, it is not the threat of a financial meltdown or systemic bank crisis. Neither seems likely at this point. The threat has to do with a problematic bias in the federal tax code.

Before we get there, let us first recognize that financial markets are not bad in themselves. They are in fact essential to the functioning of a modern economy. They offer excellent savings and investment opportunities for people who want to build financial security for themselves; they provide households and small businesses with critical access to credit; and they allow our economy to be far more dynamic than it otherwise would be.

The last point is one we often take for granted, yet financial markets are crucial to the very functioning of our modern economy. They allow us to separate and specialize functions in the economy that otherwise would be clustered together: ownership and operational control of economic resources.

Investors on the stock market own corporations, but they do not have to operate them. This can make investors better and allow corporate leaders to specialize in performing their critical functions. Likewise, on the debt markets, creditors can lend money and constantly get a market-based evaluation of the financial solidity of their investment.

Even the often-criticized markets for derivative instruments play an important role in sharpening the informational tools available to those active in the underlying equity and commodity markets.

Simply put, financial markets constantly evaluate the performance of markets, businesses, and even entire industries, throughout our economy. They can make or break both individuals and corporations; the stock market and the market for corporate debt can give a corporate CEO the career of a lifetime, or end that career by mercilessly exposing his or her failure. Such events, and even regular ups and downs in corporate values, provide critical information for investors, from households to managers of large pension funds.

Governments have also been given exceptional financial opportunities, thanks to the international markets for sovereign debt. Together with credit-rating institutions, buyers and sellers of treasury securities produce real-time assessments of how reliable governments are as debtors. This is both a blessing and a curse: on the one hand, it has become difficult for governments to default on their debt; on the other hand, it has become easy for governments to borrow generous amounts of money.

Many governments in Europe, and certainly the United States government, have become so used to financing part of their spending with money borrowed on the sovereign debt markets, that it is not even a matter of much debate. This makes their budgets vulnerable to re-evaluative corrections in the market, such as when interest rates rise because investors are not entirely confident that a government will be able to repay its debt.

However, the influence of financial markets on government budgets is greater than that. The government power to tax has, of course, reached the financial markets. There are taxes on the income that we earn from owning and trading corporate stock, private and government debt, and other assets. Many income-tax systems put a heavier tax burden on high-income households than on those who earn modest money, and the U.S. federal tax code is no exception.

According to data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS, the federal tax agency), in 2019 the highest-earning 1.1% of American taxpayers—all with a taxable income of $500,000 or more—earned 21% of total taxable income. At the same time, they paid 40.4% of all personal federal income taxes. Since taxes on personal income account for 84% of all federal tax revenue, this very small segment of taxpayers pays 34.5% of all federal taxes in America.

Since this is a wealthy demographic, it makes sense that they earn a substantial part of their income from investments. When their equity increases in value and they realize capital gains, they pay taxes on those. They also pay taxes on stock dividends, on interest earned on bonds, and other forms of equity-based income.

To see just how important that part of their income is, we dig further into the IRS data on income and taxes. It turns out that the wealthy 1.1% that earn more than half a million dollars per year got only 40.7% of that income from wages and salaries. They earned 37% from stock dividends, interest on corporate and government debt securities, capital gains (i.e., profitable asset sales), rental income, royalties, and various forms of non-corporate business income.

This 37% figure is high, but it is also conservatively calculated to focus only on the directly investment-oriented forms of equity-based income, i.e., those that the taxpayer tends to have direct control over. This allows us to concentrate on the direct relationship between financial markets and government revenue from individual taxes.

Simply put, the federal government depends on a very small group of Americans for a substantial part of its tax revenue. The exact number is difficult to calculate, given that tax rates differ between income from work and income from investments. The former is taxed more heavily than the latter for high-income earners. However, the numbers for how much taxes the very wealthy pay in total are significant enough to illustrate the point: financial markets can almost make or break the federal budget.

A strong stock market leads to soaring tax revenue. By the same token, tax revenue takes a beating when equity markets decline. The effect on tax payments from downturns in, e.g., the stock market is considerably quicker than the effect of lost wages and salaries. Therefore, the more a government depends on equity-based taxes for its finances, the more volatile those finances are going to be. However, even if the equity markets do not decline rapidly, they can still have a painful impact on tax collections.

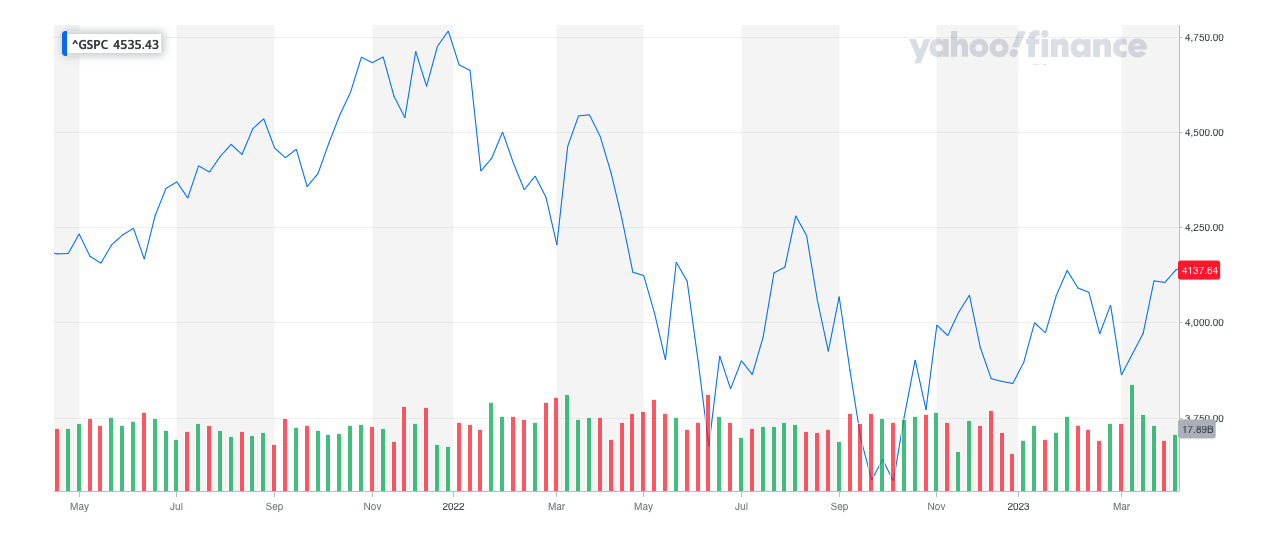

In 2022, the S&P 500 index on the New York Stock Exchange fell by 19.4%:

Figure 1

Source: Yahoo Finance

This means that on average, investors in the stock market made capital losses instead of capital gains, depriving the federal government of revenue from one of the biggest sources of equity-based income taxes. In 2019, taxable capital gains accounted for 32% of the earnings for our 1.1% highest-earning demographic—and they are not the only ones who earn equity-based income. For example, households with less than $100,000 in annual income earned $116.7 billion in equity-based income.

When the stock market declines, the likelihood increases that stock dividends will drop. The correlation between stock-market value and dividends is not very strong, but a corporation that loses in value is less likely to raise dividends than to lower them. To the extent that dividends are cut, it obviously adds to the depression of equity-based personal income.

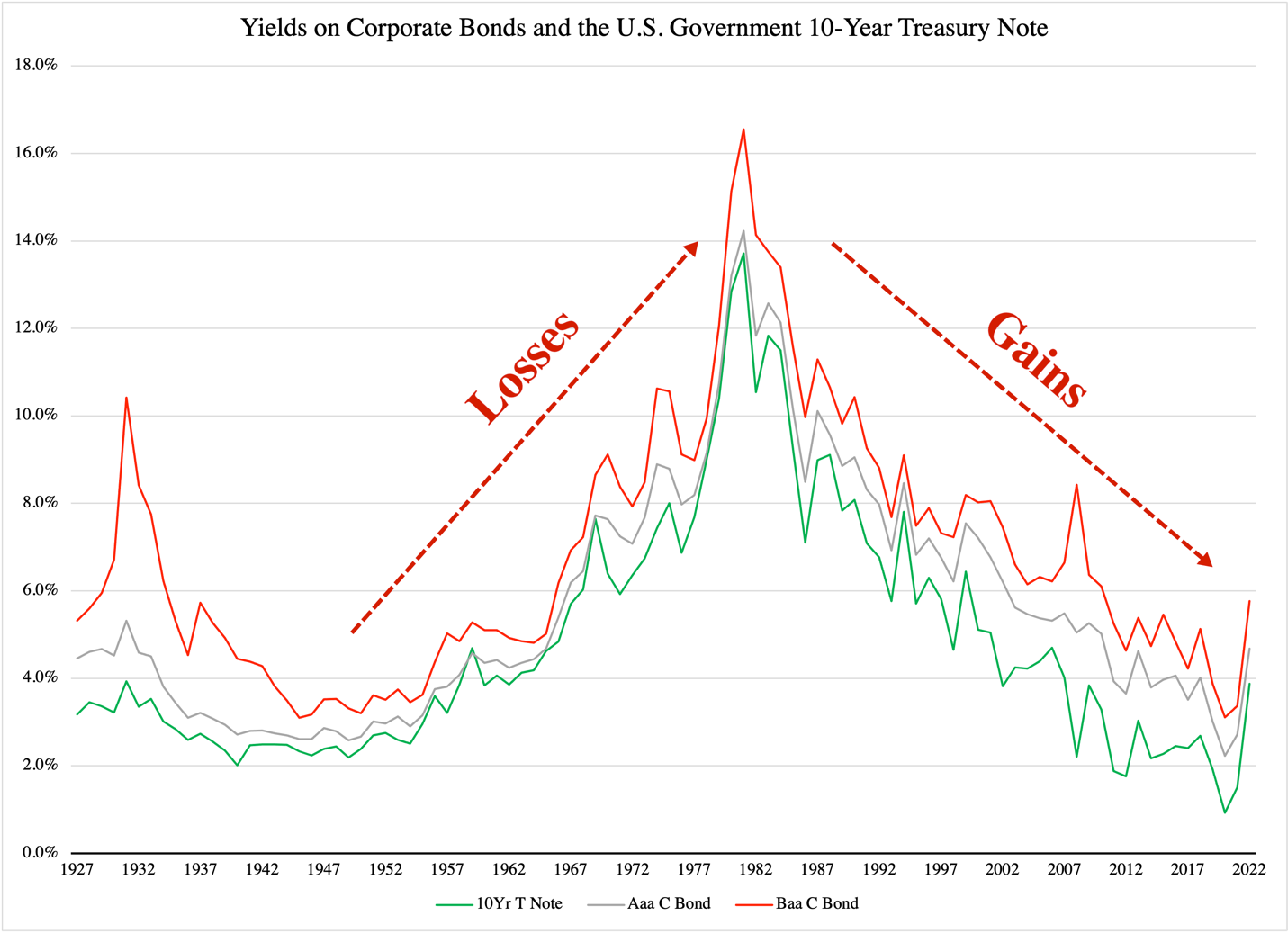

Debt markets also provide capital gains and losses, but with less volatility and less drama than the stock market. For several years in the 2010s, and generally since the early 1980s, markets for both corporate and government debt have been profitable sources of capital gains. The reason is found in how the value of a bond varies inversely with its yield:

If you buy a bond, corporate or government, for $100 and the yield is $5, the interest rate is 5%;

Suppose the demand for your bond increases, so that the price rises from $100 to $200;

Since the yield of $5 remains the same, the interest rate on your bond is now 2.5% for anyone who buys it for $200.

The same process works in the reverse, of course, which means that when interest rates rise, bondholders lose money.

Figure 2 illustrates two episodes in recent American history when gains and losses have characterized the bond markets, both corporate and government:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: NYU Stern School

It is important to note that during times of rising interest rates, owning a bond can still be profitable if the yield is high enough to compensate for the capital loss. The exception, of course, is if the investor holds the bond to its date of maturity, whereupon the issuer of the bond repays him the full nominal value of his investment.

The protracted episode with falling interest rates has placed memories of a weaker market into the annals of history. Therefore, the sharp uptick in rates, beginning last year, has been a negative surprise to many. On the balance, corporate bonds were a loss to their holders in 2022, and so was ownership of the ten-year U.S. Treasury note.

With equity markets unfavorable to tax revenue, it is not very surprising that the U.S. government, per raw data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, ran growing deficits last year:

- First quarter, $225.7 billion;

- Second quarter, $238.4 billion;

- Third quarter, $303.6 billion; and

- Fourth quarter, $322.1 billion.

This total deficit of $1.09 trillion came despite $4.9 trillion in tax revenue collected, a substantial rise over the $4 trillion in 2021. However, much of that increase took place at the beginning of the year, with payments of federal taxes increasing by 22.7% in the first quarter (year over year), 16.9% in the second quarter, and 14.4% in the third.

When the fourth quarter came to a close, the U.S. government’s tax revenue was only 5.8% higher than the year before. This is a low number, given that inflation had expanded the most important component of its tax base: personal income. A strong labor market allowed workers across the U.S. economy to demand higher pay. In the second, third, and fourth quarters of 2022, total employee compensation rose by more than 5% over the same period in 2021 (in current prices). This is the fastest advance in employee compensation in at least 20 years.

With rising income comes rising revenue from income taxes, and this effect is generally strong on government finances. Personal income provides 84% of all tax revenue to the federal government, with about two-thirds of that being general income taxes and one-third being social security taxes. However, since earners in the low-to-middle income segment do not contribute much—the 20% best-paid taxpayers pay well over 80% of all personal federal income taxes—the substantial rise in tax revenue earlier in 2022 was the result of early cash-ins from the equity markets.

As the stock market and the bond markets began declining, so did equity-based personal income, and federal tax revenue.

So far in 2023, the stock market has made somewhat of a recovery. Interest rates have stabilized, but not come down. The fate of federal tax revenue will depend on whether or not investors have made the critical transition from pursuing capital gains to focusing on a stream of income from their portfolios. With U.S. Treasury yields in many cases above 4%, even occasionally exceeding 5%, it is not difficult to build a portfolio that will produce a substantial, stable, and predictable income stream for years to come.

Such a shift in investor strategy has consequences for the federal government: if more equity-based income is coming from dividends and interest, and less from capital gains, the stream of income—and therefore tax payments—will be more stable but also less conspicuous. In 2019, taxable capital gains accounted for almost 9.2% of all taxable personal income in America.

The more a tax system relies on financial markets, the more volatile and unpredictable those tax revenues will become. There is no doubt that the U.S. government is experiencing that in real time in 2023.