EU’s plans for tougher China stance risk coming off the rails as splits emerge on multiple issues

European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen has built an image over the past year as the continent’s toughest talker on China.

But just months before the end of her first term in office, a string of high-minded legislative moves and actions targeting Beijing have run into political reality as the wheels appear to be coming off its combative agenda.

Governments are already trying to head off a lurch to the far-right ahead of European Parliament elections, sparking a bonfire of green and social legislation, while also facing the possibility Donald Trump will return to power in the United States.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

Bickering between European Union member states has also stepped up a notch, shaking the fragile unity on core issues such as Ukraine.

Meanwhile, splits are emerging on China, with France and Germany at odds on everything from solar energy and electric vehicles to trade deals and supply chains.

“There is no such thing as a Franco-German couple any more, it just doesn’t work … the division on China is typical of that,” said a French diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Last month the EU suspended a World Trade Organization dispute with Beijing over its alleged economic coercion of Lithuania. The Baltic state saw its exports to China collapse after it allowed a controversially named Taiwanese government office to open in Vilnius in late 2021.

The EU represents its members at the WTO and von der Leyen’s self-described “geopolitical commission” was under pressure to sue China, despite lawyers’ warnings that unofficial boycotts do not fall neatly into WTO rules.

Officials have struggled since day one to get firms to give evidence on the record, amid fears they could face retribution, while China loosened the unofficial embargo and some Lithuanian exports flowed.

The EU decided to suspend the case at the end of last month when a second tranche of evidence was due to be submitted. It now has 12 months to resume it but observers question whether the WTO is cut out for dealing with such matters.

“China is opaque, it is impossible to prove government intervention,” said Yeo Han-koo, the former South Korean trade minister.

Yeo worked at the trade ministry during an unofficial Chinese boycott of South Korean goods and services following the deployment of a US anti-missile system in 2016. He said Seoul had considered bringing a WTO suit, but “it took place in a very opaque manner … it’s difficult to find hard evidence”.

In legislative terms, too, the EU agenda is in danger of running aground. Von der Leyen’s flagship de-risking project, unveiled last March, has been put on the back burner amid furious resistance from member states.

Key tenets of de-risking, plans to screen outbound investments and impose export controls kicked a hornets’ nest.

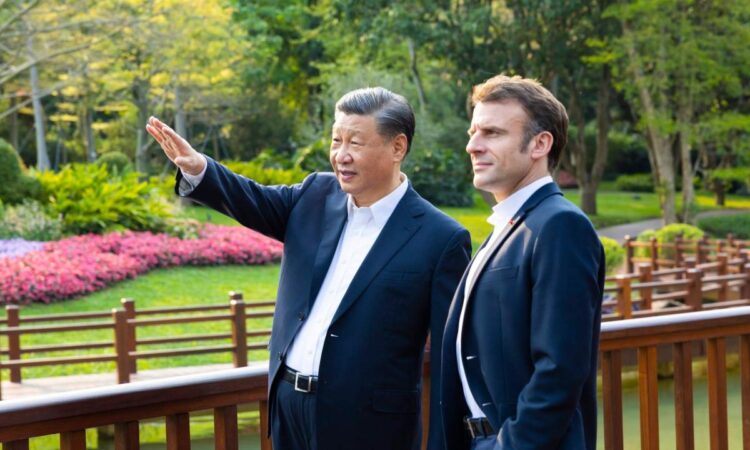

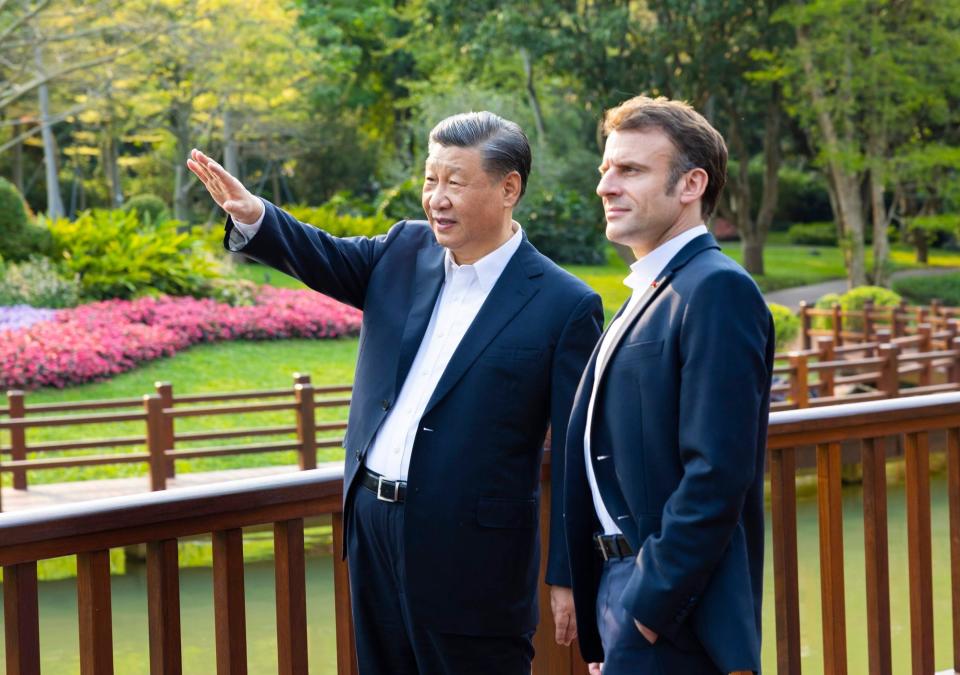

Emmanuel Macron, pictured with Xi Jinping in Guangdong province last year, is expecting the Chinese leader to visit France later this year. Photo: EPA-EFE alt=Emmanuel Macron, pictured with Xi Jinping in Guangdong province last year, is expecting the Chinese leader to visit France later this year. Photo: EPA-EFE>

Some capitals were angered by the conflation of national and economic security, the perceived “power grab” by Brussels, and what one diplomat described as the “blind following” of US China policy.

The policy has been kicked into 2025, with insiders believing its best chance of succeeding may be based on Beijing’s own actions. “There will be plenty of wake-up calls on the road ahead,” one official said.

Tough corporate supply chain rules – that would force big businesses to conduct stringent social, labour and environmental audits of their suppliers – are also at risk of collapsing.

A final vote set for Friday was postponed at the last minute amid fears it would not pass. Germany said it would abstain under pressure from the business lobby, with Finland and others reported to be following Berlin.

Businesses fear the plans could push them out of the Chinese market, with one senior lobbyist questioning how they could comply with Beijing’s vague anti-espionage and data outflow rules while providing the information Brussels requires.

A forced labour ban being negotiated between the European Parliament and Council, which represents member states, could face a similar fate. The law was written with China in mind, due to allegations of forced labour in Xinjiang, although it is not named directly.

Negotiators must strike a deal by March 9 or it will be mothballed until after June’s European Parliament elections, when the political landscape could look very different. Talks, however, are proving tricky.

“Neither commission nor member states want to take responsibility for inspections. They don’t want to say they unleashed this administrative monster before elections,” said one person involved.

According to two sources, one solution is to outsource the ban’s administration to the European Labour Authority in Bratislava.

But again the law is threatened by Germany abstaining under the influence of the pro-business Free Democratic arm of its coalition.

The EU faces a related dilemma over Chinese solar panels. There it is torn between calls for a ban on panels linked to Xinjiang and broader import quotas, and fears it cannot reach its climate goals without these imports.

Several officials and diplomats have described it as a classic example of competing policy aims. It wants to do “everything at the same time”, said one official, but it is unclear what the priority is.

Last month EU trade officials held in-depth discussions on measures available to protect the solar industry from Chinese imports, people familiar with the discussions said, but held fire because of divisions within the industry and among member states.

Behind the scenes, officials fret about Chinese retaliation and the impact of a solar trade war on its ability to hit its climate targets.

The bloc’s finance chief Mairead McGuinness said on Monday it needs “access to affordable solar panels to fuel the green transition and unlock the economic opportunities”, and Europe’s own industry currently relies on Chinese-made components.

One major vulnerability is solar inverters, known in the industry as the “brain of a solar system” that enable solar power to be transmitted to electricity grids. Without these the whole industry could be imperilled.

But Europe’s biggest supplier is Huawei Technologies, which the EU is trying to get out of its 5G network at a time when there has been little debate about the fact it supplied 26 per cent of Europe’s inverters in 2021, according to consultancy Wood MacKenzie.

The solar debate is symptomatic of the wider Franco-German division at the heart of EU policy.

France, which generated less than 5 per cent of its electricity using solar power last year, would back curbs on Chinese products. In stark contrast, Germany is increasingly reliant on green energy and strongly opposes such measures.

France was also behind a probe into Chinese-made electric vehicles that infuriated the Germans, whose firms would be disproportionately hit by import duties.

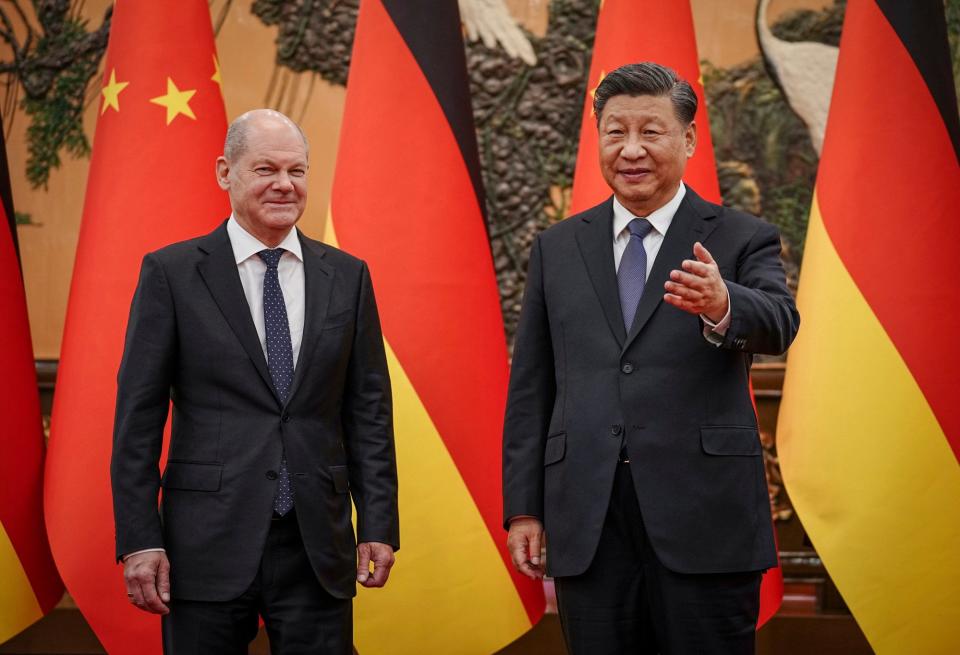

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, pictured with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing in late 2022, will return to China in April. Photo: AP alt=German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, pictured with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing in late 2022, will return to China in April. Photo: AP>

“We don’t understand each other,” said the French diplomat, who described the German idea of strategic autonomy as being “we can do whatever we want with partners, and then we decide how strategic we are about it”.

They added: “Whereas the French think everything has to be done and decided in Europe before we reach out to anyone else.”

Berlin strongly backed a push for a free-trade deal with the South American Mercosur bloc that could help the EU de-risking process by weaning it off Chinese minerals.

But France vetoed the deal, as President Emmanuel Macron seeks to court the farmers’ votes ahead of the European elections.

Meanwhile, the pair are vying for the attentions of Chinese leader Xi Jinping. A business source confirmed that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz will go to Beijing in April accompanied by industry representatives.

Macron, on the other hand, is expecting France to be Xi’s first post-Covid European destination. “I’d say before the EU elections, with Macron wanting to put on a show of power to change the course of what looks like a very bad result for him,” the French diplomat said of the timing.

A senior EU official said Serbia was also going to be on Xi’s itinerary.

In the midst of this chaos, Beijing is looking for openings.

Its ambassador to Brussels Fu Cong recently told senior EU officials he had a direct order from Foreign Minister Wang Yi to resurrect the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment that collapsed in the wake of tit-for-tat sanctions over China’s human rights record.

Such a move appears unlikely, but sources said Fu had been encouraged by von der Leyen mentioning the deal at a summit in Beijing in December.

This article originally appeared in the South China Morning Post (SCMP), the most authoritative voice reporting on China and Asia for more than a century. For more SCMP stories, please explore the SCMP app or visit the SCMP’s Facebook and Twitter pages. Copyright © 2024 South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright (c) 2024. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.