(Bloomberg) — Bogdan Prelipcean used his earliest paychecks to help his parents build an indoor bathroom.

A decade-and-a-half later, the 33-year-old Romanian has a new-build apartment, two cars and a motorcycle.

That transformation is the result of something that more than 100 million people in eastern Europe have been dreaming of since the fall of the Iron Curtain: European Union membership made his country rich.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

EU leaders are meeting in Granada, Spain, this week to contemplate another wave of expansion with a new pro-Russian government set to take power in Slovakia and the US struggling to approve more aid to Kyiv. But all the same, that dream is starting to flicker again in war-torn Ukraine, neighboring Moldova and the western Balkans.

“There’s no comparison anymore in the quality of my family’s life,” said Prelipcean, who works at a tech company in Iasi, a city of about a million people near Romania’s border with Moldova.

At the point when the EU began to open its doors to its neighbors in the east, half of the Romania’s 19 million people lacked indoor plumbing and GDP per capita was just over a third of the EU average, more or less where Ukraine’s was before the Russian invasion. That figure is now 77% and still climbing.

Over the next decade, Romania could double its economic output, according Dinu Bumbacea, country manager for consulting firm PWC, who’s surveyed companies on their investment plans and factored in another massive wave of EU funds.

Ukraine was seeking to follow that path too a decade ago, before its Kremlin-backed government swung back toward Moscow, triggering the Maidan revolution and the chain of events that led to Europe’s biggest conflict since World War II.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Now the EU has offered Kyiv a path to membership in what’s expected to be an uncertain, years-long process. That journey will require an end to the fighting as well as major reforms in the economy, the battle against corruption, and the streamlining of institutions to meet EU norms.

Romania’s accession offers lessons that can help Kyiv along the way and offer an indication of the potential rewards. Bucharest has become a determined supporter of faster accession talks for Ukraine and its other neighbors, Moldova.

“Romania couldn’t reform itself without the European Union,” Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu said in an August interview with Aleph News TV. “Without the EU and NATO we would be a fragile country.”

When Romania became a member, it finished retooling its centrally planned economy to open up to the European market. Successive governments sold state-owned firms, eased trade restrictions and, most importantly, fixed the courts to help root out corruption.

That helped Romania catch up with traditionally wealthier Hungary to the West, while also pulling away from Bulgaria, the Black Sea neighbor with which it once vied for bottom spot in EU rankings on poverty and graft.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Read More About Ukraine and Eastern Europe:Russia May Be About to Get a New Friendly Leader in EuropeZelenskiy Is Showing the Strain as His Allies Turn Up the HeatWartime Alliance at Risk as Poland and Ukraine Fight Over GrainThe Far Right Is Advancing in a Vulnerable Europe Again

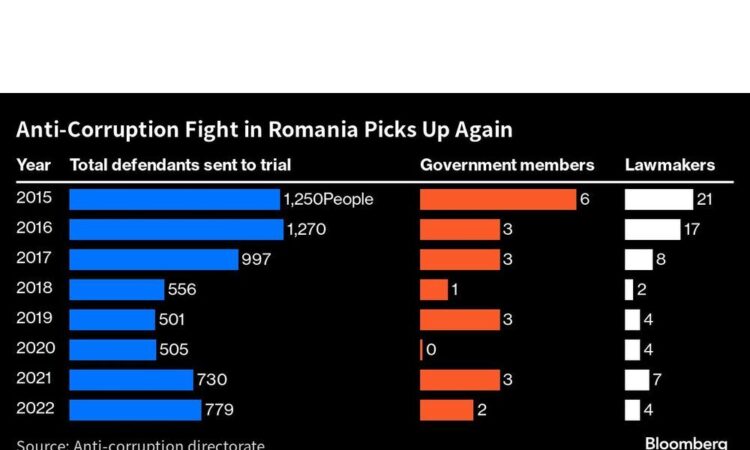

Spearheaded by former anti-graft prosecutor Laura Codruta Kovesi, who now leads the EU’s first Public Prosecutors Office, Romania jailed scores of government officials over the last decade, including prime ministers, cabinet officials and members of parliament.

It took fierce determination from Kovesi to change people’s mentality and tackle structural corruption at all levels in the state, according to a person who worked with her, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the issue. The drive was supported by an EU mechanism that promoted a judicial overhaul completed last year, and Kovesi’s campaign won her the adoration of Romanians.

But it also made her enemies. She was fired in 2018 after then-Justice Minister Tudorel Toader — who accused her of damaging Romania’s image abroad — won a Constitutional Court decision that she had exceeded her authority. The ruling was later overturned by the EU’s highest tribunal.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Decisions like that highlight the risks that could still derail Romania’s progress, in a region where populist governments in Hungary and Poland have sacrificed EU funding for their own political gain. A newly-formed nationalist party entered the Romanian parliament in 2021 and is now polling at 20%. So far the country’s two biggest parties have worked together to keep the nationalists away from power.

But high-profile graft cases continue to roil the political scene, and some trials languish for years in overcrowded courts, as a warning against complacency. The anti-corruption directorate has recovered over €1 billion in damages in since 2015 and significantly cut down on official sleaze.

“Every act of corruption means less money for education, healthcare or defense,” Chief Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Marius Voineag said in an interview. “It means a waste of public resources and is a major obstacle for Romania’s development,” he added, warning that graft remains a problem and more progress is needed.

Kovesi, from her new position in the EU prosecutor’s office, may try to replicate the model in Ukraine, where corruption is seen as the biggest challenge facing the country after the Russian invasion. Less than a month after the war began, Kovesi traveled to Kyiv to seal a cooperation agreement with Ukraine’s chief prosecutor.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Over the past decade and a half, the transformation of Romania’s institutions has attracted foreign investment, creating jobs and bringing knowhow to increase productivity.

From 2010 to 2021, investment from abroad almost doubled to more than €100 billion ($110 billion), according to the central bank, as foreign companies flooded in to build everything from car factories to tech offices. Last year, the inflow of money hit a record €11 billion.

Among the biggest investors are Ford Motor Co. and Renault Group’s Dacia, which now produce more than half a million cars a year in Romania between them. Tire maker Continental AG has invested €2.2 billion and tech giants including Amazon, Microsoft and Oracle have opened and expanded research centers.

At the same time, successive governments tapped into EU development funds to build more than 700 kilometers (430 miles) of highways, improve schools and public services and provide amenities including fixed-line internet access — and, of course, sewers.

While Romania has at times struggled to effectively tap the billions of euros in EU funds on offer, political parties have put aside differences in a push to maximize funding. To date, the country has netted more than €53 billion from the EU and has contracts in the works for another €12 billion.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

“There is a clear improvement and acceleration in terms of capacity to absorb EU funds and implement infrastructure projects,” said Lilyana Pavlova, vice president of the European Investment Bank. “You can see it and you can feel it.”

New projects coming on line, including a €650 million zero-emission tire plant being built by Nokian Renkaat Oyj, a €1.4 billion battery plant by Belgium’s Avesta Battery and Energy Engineering and a €4 billion investment in the Black Sea Neptune Deep natural gas project.

While the GDP per capita numbers are swollen by the fact that millions of Romanians left to seek work in the West after EU accession, second quarter suggests living standards are set to surpass those in Poland, the region’s biggest economy, as soon as this year and it has vastly outstripped neighbors that didn’t join the EU, such as Serbia.

Outstripping Neighbors

Perhaps the most stark comparison is with Bulgaria next door, the result is striking.

The two countries joined the EU on a similar footing, as the bloc’s poorest and most corrupt members – just as Ukraine would probably be if it ever secures membership.

While Bucharest focused on tackling corruption, successive governments in Sofia failed to match those efforts and Bulgaria’s living standards are now just 60% of the EU average, 17 percentage points lower than in Romania.

Bulgarian Finance Minister Assen Vassilev said at least part of that was that is down to Romanian prosecutors.

“Romania was much faster with the rule of law reforms,” Vassilev said in an interview. “While painful at the beginning, that allowed them to create a business environment that was very conducive.”

—With assistance from Slav Okov, Irina Vilcu and Gina Turner.