Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6/2023.

This box examines how euro area firms perceive climate change risks as well as their investment plans and financing needs to mitigate the impacts of climate change. Between 25 May and 26 June 2023 the European Central Bank (ECB) conducted a pilot round of the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), which for the first time included specific questions related to the impact of climate change on euro area firms.[1] Specifically, firms were asked about: i) the importance they attach to the consequences of physical and transition risks, ii) their investment behaviour to mitigate risks or reduce the negative environmental impact of their economic activities; iii) different financing sources chosen to fund climate change-related investments and iv) potential impediments to the necessary financing.

Existing literature commonly groups climate risks, based on their drivers, into physical risks and transition risks. Physical risks arise from the physical impact of climate change on the economy, including extreme weather events and changing climate patterns. Transition risks arise from the implementation of stricter climate standards, regulations and carbon pricing to foster the transition to a low-carbon economy. Physical risks can be further subdivided into acute physical risks, which are related to natural hazards such as wildfires, storms and floods, or chronic risks which are related to longer term shifts in climate patterns resulting in the degradation of natural environment and depletion of natural resources.[2]

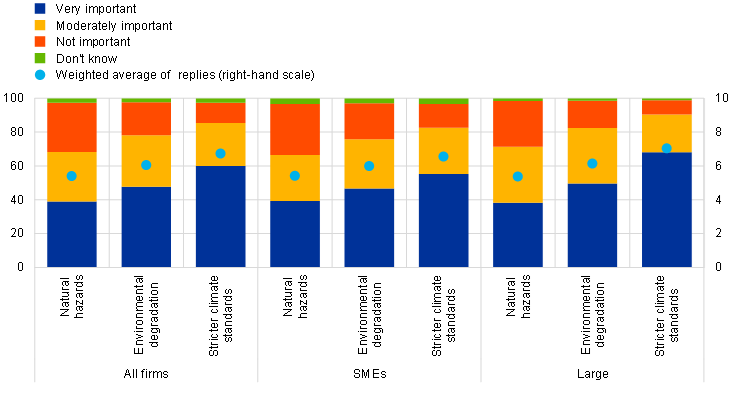

Concerns about the consequences of climate change over the next five years are quite widespread across euro area firms (Chart A). In the survey, 60% of euro area firms indicated that transition risks related to stricter climate standards are “very important” for them.[3] Large firms were more concerned about transition risks arising from stricter climate standards, regulation and carbon pricing than small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Moreover, 39% of the respondents were very concerned about natural hazards (score of 7 and above on a scale of 1 to 10), while 48% reported the same level of concern about environmental degradation. This indicates that there are more firms concerned about the consequences of environmental degradation, even if they do not judge their own activities to be vulnerable to immediate natural hazards.

Chart A

Importance of climate change consequences for euro area firms over the next five years

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and European Commission SAFE.

Notes: Firms were asked to indicate how important the consequences of climate change are for their current business model five years ahead on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). On the chart, the scale has been divided into three categories: low (1-3), moderate (4-6) and high importance (7-10). The average score is weighted by size class, economic activity and country to reflect the economic structure of the underlying population of firms.

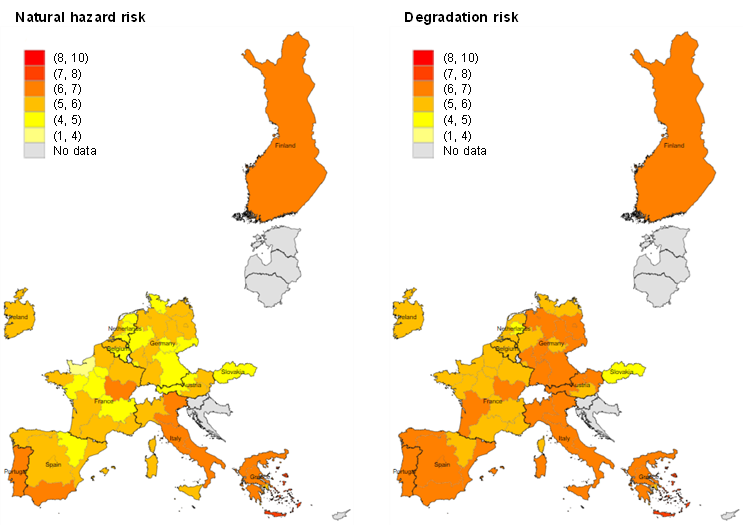

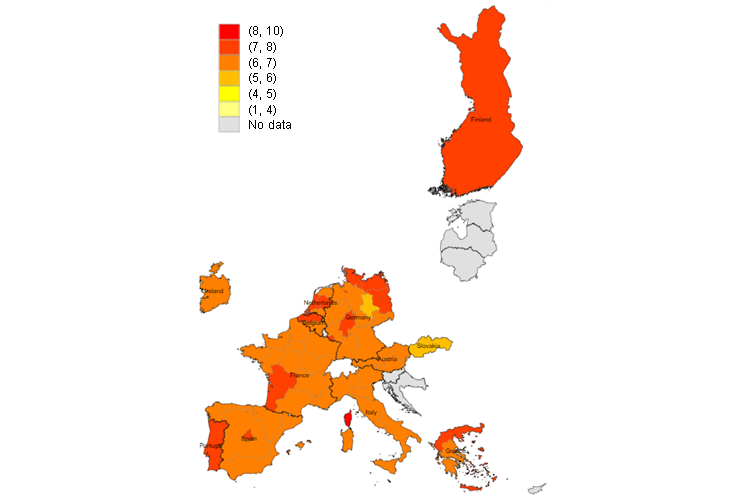

Firms are concerned about physical risk originating from climate change particularly in coastal areas and regions where the occurrence of wildfires has been higher, whereas transition risk concerns are more evenly spread across regions in the euro area (Chart B). A regional analysis of the importance that firms attach to the consequences of climate change reveals that concerns over natural hazards are more prominent in coastal regions or areas historically vulnerable to droughts, wildfires or floods, particularly in Southern European and Nordic countries (Chart B, panel a, left). By contrast, concerns about environmental degradation are concentrated mostly in regions affected by tourism or heavy industry (Chart B, panel a, right). Meanwhile, transition risk is not only a concern for more firms than physical risk is, as shown in Chart A, but is also more uniformly distributed across euro area regions (Chart B, panel b). Since climate regulations are mainly determined at national or European level, the level of importance that firms attach to transition risk is more homogeneous within each country compared with concerns about physical risk, which are more regionally clustered.

Chart B

Importance of consequences of climate change for the next five years – geographical distribution

a) Physical risk

(weighted average scores)

b) Transition risk

(weighted average scores)

Sources: ECB and European Commission SAFE.

Notes: The maps show the weighted average score for the importance of consequences of climate change for firms over the next five years by main socio-economic regions based on NUTS1 (2016 classification) in the euro area. Firms were asked to indicate how important the consequences of climate change (natural hazards, environmental degradation and stricter climate standards) are for their current business model five years ahead on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). The weighted average scores at NUTS1 level are averages of the responses within each bracket weighted by size class, economic activity and country to reflect the economic structure of the underlying population of firms.

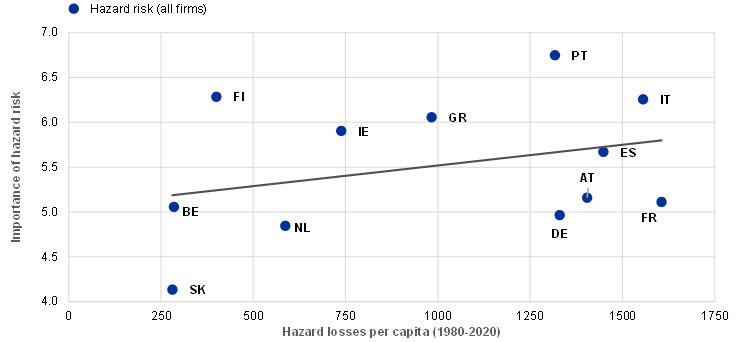

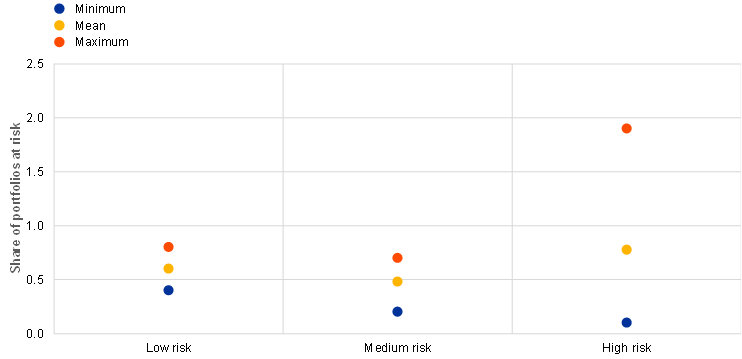

Concerns of firms about natural hazard risks at country level reflect past losses and are correlated with expected future risks (Chart C). The upper panel of Chart C shows a clear positive relationship between the survey-derived weighted average score of the relevance of natural hazard risks for firms’ business activity and cumulative past losses incurred from different disasters in the last 40 years at country level.[4] However, the correlation is less strong when comparing survey-based country scores – grouped into low, medium and high risk buckets – with a forward looking measure derived from approximating banks’ expected annual losses on corporate loans due to natural hazards in a climate baseline scenario (Chart C, bottom).[5] Higher risk assessments by firms are only weakly correlated with significantly higher expected future losses stemming from climate change. Moreover, in buckets where firms attach high importance to the risk of natural hazards, the distribution of expected losses is wider. This could indicate that future climate change developments are not yet fully accounted for in the risk assessments of firms, given the degree of uncertainty surrounding future climate scenarios.

Chart C

Importance of natural hazard risks five years ahead with respect to past and expected losses due to hazard risk

a) Historical hazard risk losses

(y-axis: weighted average scores for survey replies; x-axis: EUR millions)

b) Expected future risks

(y-axis: percentage; x-axis: risk groups of survey replies)

Sources: ECB and European Commission SAFE, Integrated Natural Catastrophe Database (CATDAT), ECB analytical indicators on physical risk and ECB calculations.

Notes: Firms in SAFE were asked to indicate how important the consequences of natural hazard risks are for their current business model five years ahead on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). The weighted average scores plotted on the y-axis of panel a are averages of the responses at country level using the weighted number of respondents. The x-axis in panel a indicates the value of economic damage caused by weather and climate-related extreme events for the period 1980-2020. The y-axis in panel b shows the distribution of normalised exposure at risk, which quantifies from banks’ perspective the share of portfolio at risk via their loans, debt, and equity exposures to non-financial corporations at country level. On the x-axis of panel b, countries with average hazard risk score values below 5 are classified as low-risk, medium risk if the value ranges between 5 and 6 and high risk in case the value is above 6. Panel b excludes NL since the expected annual loss measure does not consider the current and future mitigation measures leading to NL being classified as an outlier.

Most firms judged to have sufficiently invested or plan to invest to address climate change. Half of euro area firms judge that they have sufficiently invested to dampen their own negative environmental impact, while 24% of firms plan to invest within the next five years. At the same time, 32% indicated that they have invested and 23% that they plan to do so within the next five years to mitigate the impact of natural hazard risk. Across size classes, large firms seem to be more active in reducing the negative environmental impact of their activity.

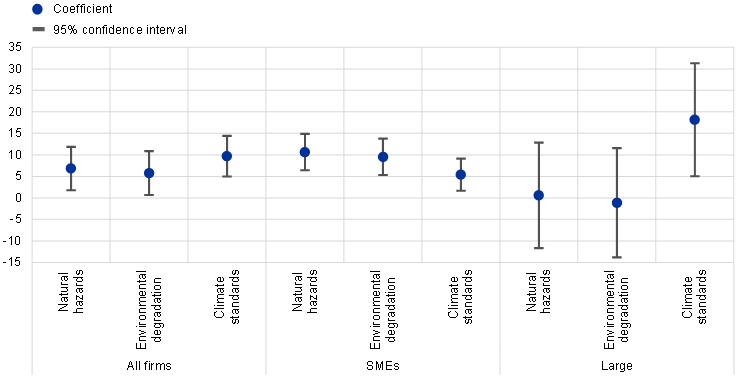

Stricter climate standards provide a stronger incentive for firms to invest in climate change mitigation than natural hazards or the degradation of the environment (Chart D). Reduced-form regressions investigating the joint impact of the three main risks of climate change on firms’ climate-related investments suggest that stricter climate standards might drive firms to invest relatively more (10 pp) than natural hazard risks (7 pp) or environmental degradation (6 pp).[6] However, when focusing only on SMEs, stricter climate standards are not significantly more likely to affect investments compared with concerns related to natural hazards or the degradation of the natural environment. By contrast, for large firms, stricter climate standards are more important for their investment plans. Overall, it might be easier for firms to assess the costs associated with stricter standards (e.g. a carbon tax), than the likelihood and consequences of a natural disaster. Therefore, stricter standards might provide a stronger incentive for firms to invest in climate change mitigation. Large firms should be also more aware of their climate impact given the increasing pressure to report on sustainability issues.[7]

Chart D

Consequences of climate change and investment to mitigate its impact

(percentage points)

Sources: ECB, European Commission SAFE and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart plots regression coefficients showing the impact of consequences of climate change for euro area firms for the next five years on realised or planned climate-related investment. Dummy variables natural hazards, environmental degradation and stricter climate standards take value 1 if the firm indicates that these concerns are very important, i.e. taking at least value 7 on a scale from 1 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). The outcome variable is 1 if firms have invested or plan to invest within the next 5 years in mitigating the risk of natural hazards or their own negative environmental impact. We control for firms’ turnover, labour costs, non-labour input costs, interest expenses and the regression covers firm size (employment), time, industry and location fixed effects on the NUTS1 level. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

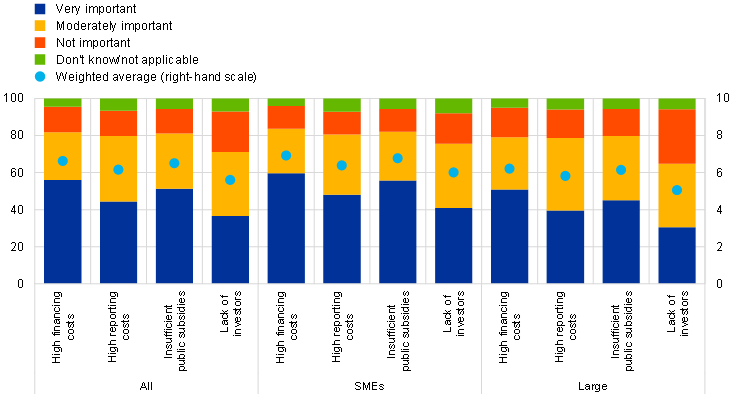

Several obstacles were indicated as hampering access to the financing necessary for investments to mitigate natural hazard risks or comply with stricter climate standards (Chart E). More than half of the firms indicated too high interest rates or financing costs and insufficient public subsidies as being very important obstacles to securing climate-related investment.[8] Firms may consider the costs to be high as they might not be sufficiently internalising the benefits of addressing climate change risks. Too high environmental reporting costs were also quoted as a very important obstacle by 45% of firms, whereas 37% of firms considered the lack of investors’ willingness to finance green investment a very important concern. For SMEs, all obstacles to securing financing for investment are of greater concern than for large firms.

Chart E

Obstacles to securing financing for investments to mitigate natural hazard risks or comply with stricter climate standards

(percentages)

Sources: ECB and European Commission SAFE.

Notes: Firms were asked to indicate how important the obstacles are to securing financing for investments to mitigate natural hazard risks or comply with stricter climate standards on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). On the chart, the scale has been divided into three categories: low (1-3), moderate (4-6) and high importance (7-10). The sample comprises firms that already invested or plan to invest in green policies.

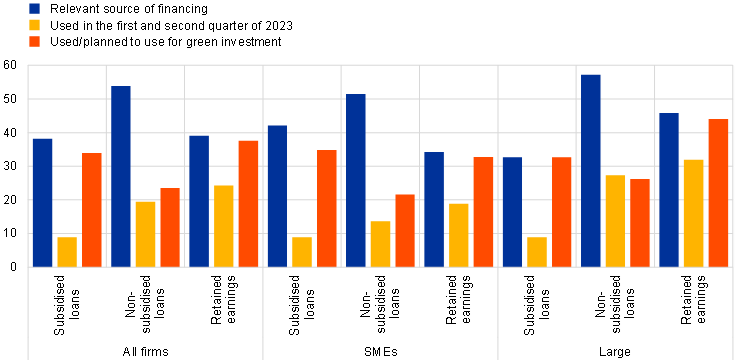

Survey results highlight the important role played by public loan guarantees and private sector funds in directing resources towards the greening of the economy (Chart F). Besides non-subsidised loans and retained earnings, subsidised loans are a relevant source of financing for enterprises, more so for SMEs than for large firms. In the first half of 2023, the SAFE indicate that 19% of firms used non-subsidised loans to finance their business, whereas only 9% of firms used subsidised loans. At the same time, for climate-related investment purposes, 24% of firms plan to use non-subsidised loans and a larger share of firms plans to use subsidised loans (34%). Recent results from the ECB’s euro area bank lending survey highlight banks’ enhanced attention to climate risks and that the increasing reporting requirements alongside with fiscal support measures have a beneficial impact on loans for green firms.[9] For instance, banks reported an easing of credit standards and of terms and conditions for new loans to green firms, while an overall tightening was reported for non-green firms. In this regard, banks arguably might still perceive lending to non-green firms riskier compared to their green counterparts. [10] The use of public guarantees might thus mitigate this risk, thereby facilitating the climate transition process also for firms that, while having transition plans, are not considered green by banks.

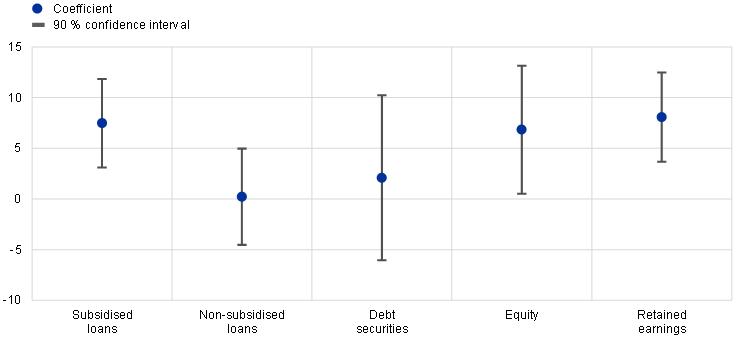

From the side of firms, reduced-form regressions investigating the joint impact of the sources of finance on climate related investments confirm that the use of subsidised loans and retained earnings increases investment probability by 7 pp and 8 pp, respectively (Chart F, panel b). In addition, results highlight the importance of equity capital to foster firm investment in mitigating natural hazard risk and their own negative environmental impact.[11]

Chart F

The use of financing sources for investment to mitigate exposure to hazards and climate policy risks

a) Use of financing sources

(percentages)

b) Impact of sources of finance on climate related investment

(percentage points)

Sources: ECB, European Commission SAFE and ECB calculations.

Notes: Data refer to enterprises that have already invested or plan to invest in green policies. In panel a, blue bars show the share of firms that consider certain types of financing relevant for their business (have used them in the past or consider using them in the future), whereas yellow bars show the share of firms that have used a certain type of finance in the first quarter or the first two quarters of 2023. Red bars show the share of firms that used or plan to use certain types of financing for investment to mitigate exposure to hazards and climate policy risks. Panel b shows regression coefficients for sources of financing for euro area enterprises on realised or planned investment with climate-related purposes. Dummy variables subsidised loans, non-subsidised loans, debt securities, equity and retained earnings take value 1 if the firm indicates that it uses or plans to use these sources of financing for green investment. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if firms have invested or plan to invest within the next five years in mitigating the risk of natural hazards or their own negative environmental impact and 0 if the firm has not invested. The regression covers size, time, industry and location fixed effects on the NUTS1 level. Whiskers represent 90% confidence intervals.