The model that the Bank of England uses to make economic forecasts has “significant shortcomings”, a review commissioned by the Bank has found as it recommended dedicating more resources to the job.

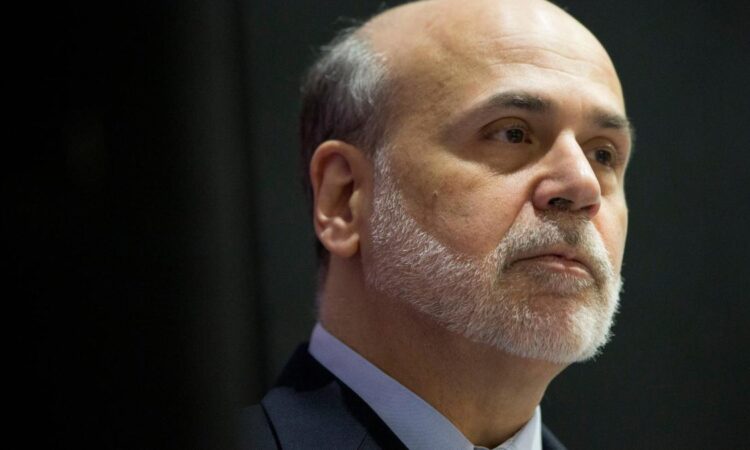

A report by former US Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke found that Bank staff were using “out-of-date” software which had not been properly maintained.

It found that staff were performing some functions manually which “ideally would be executed automatically.”

The review was called last year after Bank forecasts were repeatedly wide of the mark in a period of economic turbulence.

At a time when the economy is fluctuating it is always harder to accurately predict what will happen next, but the Bank brought in Dr Bernanke after receiving public criticism.

But the review found in part that while the Bank’s forecasts had been off at times, it had done better than some other central banks.

In the critical period between the second quarter of 2021 and the third quarter of 2023, the Bank of England did better than the European Central Bank of Sweden’s Riksbank in forecasting inflation. In the same period it did worse than the central banks of Canada, Norway and New Zealand. The US Fed does not publish comparable forecasts.

In the same period the Bank was the second-worst at forecasting gross domestic product (GDP). At one point, it forecast the longest recession in decades, which did not happen.

The former Fed boss made a series of recommendations, including that software should be updated and modernised “with high priority”.

The new software should ensure that data input “is automated to the extent possible”, especially for “routine operations”.

There should be a “significant increase in dedicated staff time” in maintaining and developing the models the Bank uses. In the longer term the Bank should consider replacing “or, at a minimum, thoroughly revamping”, the current COMPASS system.

The report also said, although did not formally recommend, that the Bank could start producing its own forecasts of what might happen to interest rates in future, which could help inform its inflation forecasts.

At the moment the Bank publishes forecasts based on two scenarios of what might happen with interest rates – one that rates stay unchanged from where they are now, and another which is based on what markets think will happen to rates.

Many other central banks – including those in the US, Sweden, Norway and New Zealand – produce their own interest rate forecasts, although do it in slightly different ways.

These forecasts are not promises of what the Bank will decide in the future, but can serve to give insight into their thinking and create better forecasts.

“The most serious problems we found in our review are the deficiencies of the Bank’s forecasting infrastructure – the tools the staff uses to produce the quarterly forecast and supporting analyses,” the report said.

It added: “Some key software is out of date and lacks important functionality.”

The review said that “insufficient resources have been devoted to ensuring that the software and models underlying the forecast are adequately maintained”.

It added: “In particular, the baseline economic model, known as COMPASS, has significant shortcomings.”

Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England said: “We welcome this important review and its recommendations.

“This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to update our approach to forecasting, and ensure it is fit for our more uncertain world. We have set out our initial response today, and are committed to taking action on all of Dr Bernanke’s recommendations.”