This is a joint blog with Michael Weilandt.

It is an undisputed fact that American pharmaceutical prices are the highest in the world.

More on:

Big pharmaceutical companies argue that this is essential to sustaining pharmaceutical innovation (Novo Nordisk suggests otherwise, but that’s a different argument).

Budget hawks argue that there are easy savings to be had from joining the rest of the world in using the government’s purchasing power to strike a better deal.

But no one doubts that U.S. prices are high.

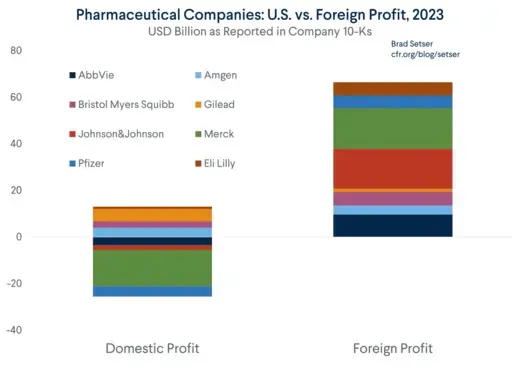

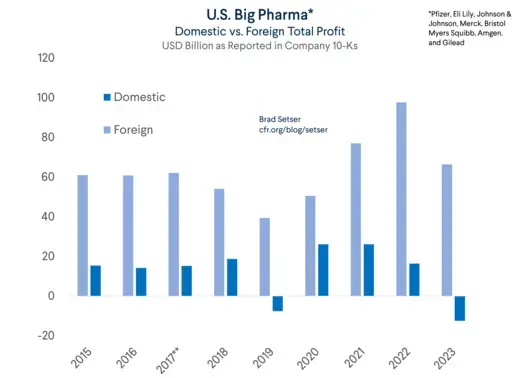

However, those high prices do not translate into high reported profits in the United States. Rather, the contrary: large pharmaceutical companies generally report losing money in the U.S.

No need to take our word for it.

More on:

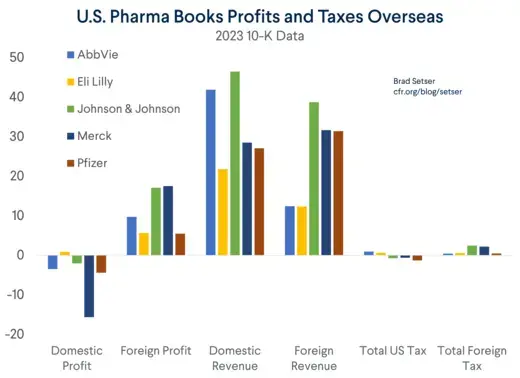

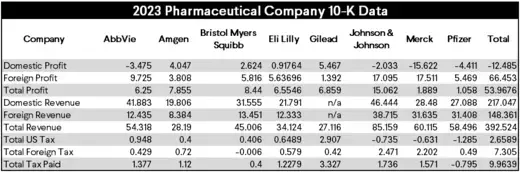

In 2023, Pfizer reported losing $4.4 billion in the United States, AbbVie $3.5 billion, Merck $15.6 billion, and Johnson & Johnson $2.03 billion. Of the biggest U.S. firms, only Eli Lilly appears to have eked out a small ($0.9 billion) profit in the United States.*

This is not an aberration. Large American pharmaceutical companies consistently report modest profits in the U.S., and large profits abroad (even though drug prices and revenue are much higher in the United States). 2023 is no different than 2022 or, for that matter, 2021.

For a comprehensive look at the 10-K data, refer to the table at the end of this blog.

So high prices strangely seem to correlate with large losses. This, of course, is a clear sign that pharmaceutical companies live in a world marked by transfer pricing and tax arbitrage.

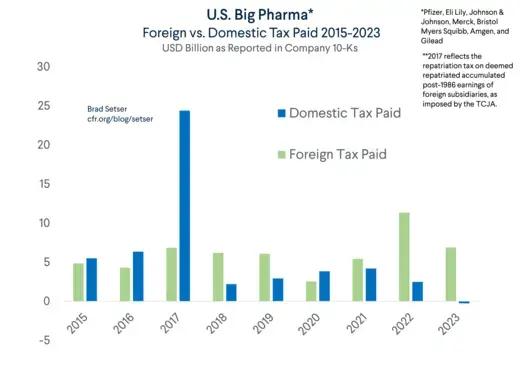

Losses in the U.S., in turn, translate into a very small U.S. income tax liability.

Most pharmaceutical companies do pay some tax globally. Most seem to pay effective tax rate of 10 to 15 percent absent tax losses tied to a major purchase or a large reorganization (2023 had a lot of charges related to the reorganization of firms’ operations in Puerto Rico). But these companies typically don’t pay the bulk of their income tax bill in the United States.

Again, no need to take our word for it.

Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck all had no U.S. tax liability in 2023 (they have some tax losses to carry forward though).

AbbVie did pay a bit of U.S. tax, even though it books all of the profits on its blockbuster drug Humira in Bermuda for one simple reason: Bermuda has no corporate income tax. AbbVie thus owed the United States a bit of Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) tax.**

Sum up the reported U.S. tax paid of the top eight pharmaceutical companies (by revenue) and their combined U.S. tax liability in 2023 was… zero. Negative $1.3 billion to be precise.

One small disclaimer: Eli Lilly’s disclosure is less comprehensive, but we were able to estimate the foreign-domestic split by using the reported share of domestic and Puerto Rican profit relative to the total.

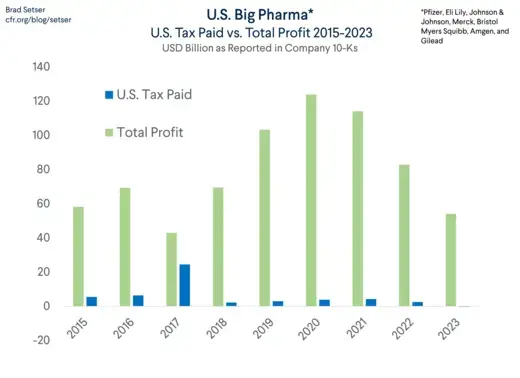

2023 isn’t really all that unusual. Tax paid in the U.S. in 2022 was positive largely because of Pfizer’s extraordinary vaccine profits (there is reason to believe that Pfizer wasn’t able to shift those profits out of the U.S., as the U.S. more or less financed the initial production, which was largely done at home).

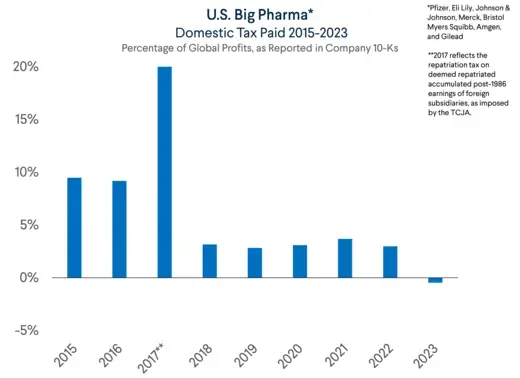

The broad trend here is clear: pharmaceutical companies are making more money than they did before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), but they are paying less tax in the U.S. than they did before that legislation.

The average effective tax rate paid in the U.S. (so U.S. tax paid versus global profit) was only 3 percent from 2018 to 2022, well below the typical effective tax paid in the US before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (see the work of Senator Wyden and his staff for more details). The big increase in tax paid in 2017 in the chart below was the one-off payments tied to the transition out of the old regime of indefinite deferral of foreign profits to the new regime of a 21 percent headline rate, semi-territorial taxation and a 10.5 percent “GILTI” minimum.

I say this not to criticize the authors of the TCJA but rather because there now should be a bipartisan consensus to reform the TCJA so that American firms that make money in the U.S. actually pay tax in the U.S.

This is a separable issue from the level of corporate income tax.

Be it 15 percent, 21 percent, or 28 percent—American companies ought to at least pay that tax on their U.S. operations and sales.***

This is an achievable goal; there are actually ways to reform the tax code to force companies selling drugs developed in the U.S. and sold to U.S. buyers to pay tax in the U.S.

In the process, pharmaceutical companies would actually be incentivized to produce their most advanced, patent-protected medicines in the U.S. rather than Ireland, Belgium, Singapore, or Switzerland. Right now, offshore production helps create the legal basis for booking profits on goods sold in the U.S. by a U.S. company offshore.

This is an “America first” proposal—it creates incentives to produce advanced medicines in the U.S. and in the process pay tax in the United States

Why are we so sure that this a realistic outcome of a well-designed tax policy?

Simple. We know that Novo Nordisk, now Europe’s most valuable company—and a highly innovative one—actually pays tax in Denmark at the Danish corporate income tax rate. That is what it discloses in its annual report (see page 9).

Swiss pharmaceutical companies also tend to pay the bulk of their corporate income tax in Switzerland; French ones pay most of their tax in France.

Only the U.S. has a tax code that allows American pharmaceutical companies to be a larger part of the tax base of Ireland, Belgium, Bermuda, Malta, Hungary, Singapore, and Switzerland than the United States itself. Tax paid outside the United States now consistently exceeds tax paid inside the United States. It is, as they say on the other side of the Atlantic, an “own goal.”

As an aside, Apple also now pays more corporate income tax outside the U.S. (mostly in Ireland) than in the U.S. (see note 7 in its 2023 10-K filing). This isn’t just a “pharma” issue.

It is, however, an issue that increasingly requires a solution. The current tax code for pharma is a combination of bad tax policy, bad supply chain resilience policy, and bad industrial policy.

Now for the boring bits – how does big pharma shift profit on U.S. sales overseas?

The answer is threefold:

a) The 2017 tax code created a much lower tax on global profits than U.S. profits, encouraging firms to find ways to book profits abroad.

b) Producing pharmaceuticals for sale in the U.S. outside the U.S. lets pharmaceutical companies pretend that the profits accrue to the location of production (or the location of the intellectual property rights), not the U.S.

c) Pharmaceutical companies are skilled at moving their intellectual property out of their U.S. headquarters to wholly owned subsidiaries located in low-tax jurisdictions.

To make this concrete, consider AbbVie’s tax structure.

AbbVie isn’t unique, but its structure is especially well-known as a result of the investigative work of the Senate Finance Committee, as well as some past tax litigation.

AbbVie produces Humira in Puerto Rico, a jurisdiction which for complex reasons is considered non-U.S. for income tax purposes. It does not, however, book large profits in Puerto Rico. Rather, AbbVie’s Puerto Rico subsidiary pays large royalties to its Bermuda subsidiary.

AbbVie thus books the bulk (99 percent in 2022) of its profit in Bermuda, which doesn’t collect any corporate income tax.

Before the TCJA, AbbVie had to move dividend payments from AbbVie Bermuda to AbbVie U.S. to cover its U.S. operating loss. It thus was not able to indefinitely defer the entirety of its Bermuda profit and paid some U.S. tax at the headline 35 percent tax rate.

After the TCJA, AbbVie has to pay a top-up tax to bring its overall tax rate on its international profit up to 10.5 percent. It can net any foreign tax it pays outside of Bermuda against its U.S. GILTI tax liability. This is referred to as “blending,” and it should be ended. The GILTI tax should be imposed on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis, rather than on the aggregate of a company’s foreign income. The current structure allows firms like AbbVie to blend income from low- or zero-tax jurisdictions with income from non-tax haven foreign operations (say, in Germany, France, or the UK), thereby reducing their overall tax liability.

AbbVie’s broad structure is standard: produce outside the (legal) U.S. and book income outside the U.S. Most companies have now moved away from Puerto Rico, but there is nothing otherwise atypical about this tax structure.

It is also all perfectly legal. It just should not be.

A simple principle is that U.S. companies should pay profits on their U.S. sales in the U.S. Frankly, under source-based taxation, they actually should be paying tax on all the drugs developed in the U.S. in the U.S., not just the profits from their U.S. sales.

That, unfortunately, isn’t the observed outcome of the TCJA, six years in.***

* Eli Lilly does not directly report its earnings by geographical location in its 10-Ks, but it does include language for a sufficient estimate. More specifically, it discloses the annual percentages of “consolidated income before taxes” that was generated by Domestic and Puerto Rican companies.

** Global Intangible Low Tax income (GILTI), the U.S. version of a global minimum tax created in the TCJA. I have been known to call it the Pharma Tax Cuts and Irish Jobs Act, as it generated powerful incentives to produce drugs for the U.S. market in low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland and Singapore.

*** U.S. pharmaceutical companies are making between $70 and $100 billion a year, so the ten-year revenue estimate from getting big pharma to pay tax in the U.S. is not trivial.

**** Folks like Bob Lighthizer who care about bilateral trade deficits should be pushing this, as pharmaceuticals are a big reason for the U.S runs a large bilateral deficit with Ireland and Switzerland. American pharmaceutical companies producing in Singapore rather than the U.S. for the Asian market also add to the U.S. bilateral trade deficits in Asia, as US companies are generating exports for Singapore not the United States.