EU countries and European institutions must do much more to share and centralise sensitive data, to better apprehend economic security risks and more efficiently protect supply chains from increasingly predacious geopolitical actors, writes Mathieu Duchâtel.

Mathieu Duchâtel is the director of international studies at the Institut Montaigne.

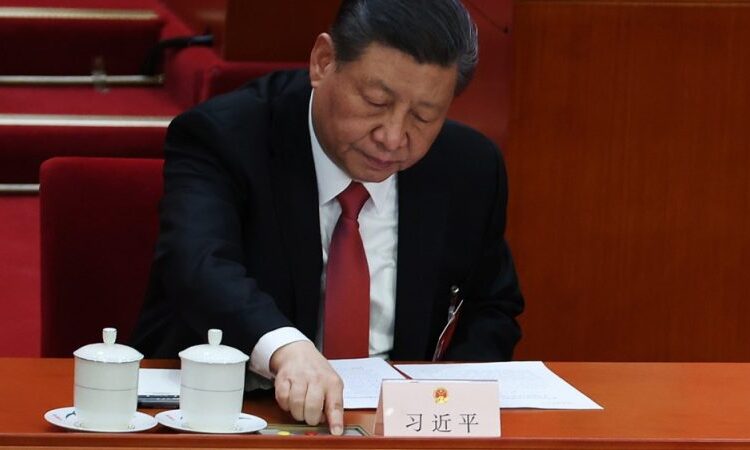

As Chinese President Xi Jinping prepares to touch down in Paris for his first visit to Europe in five years on Monday, European intelligence agencies are abuzz with activity.

Counterintelligence stories (arrests in Germany, Chinese espionage in the European Parliament and Dutch industries, and hacking targeting a prominent Belgian politician) are raising public awareness across Europe about the strained state of EU-China relations.

They also highlight a current challenge faced by European policymakers: while national security falls under the jurisdiction of national governments, economic security is an agenda driven by the European Commission.

But how can European institutions act in the absence of their own intelligence capacities?

Economic security agenda with no economic intelligence

The challenge of supply chain resilience reveals the difficulty of building a European economic security agenda without economic intelligence.

Successive crises have exposed weaknesses in Europe’s supply chains. However, efforts to mitigate these risks have primarily been undertaken by private companies and individual member states.

Without its own economic intelligence capability, the European Union’s attempts to address vulnerabilities in supply chains have yet to yield significant results.

To effectively address this challenge, the European Commission must aggregate and analyze strategic information on a scale surpassing that of individual member states and private entities. This would establish the Commission as a pivotal player in supply chain resilience decisions, benefiting all Eu countries and European businesses.

However, this endeavour faces obstacles, including the need for the European Commission to prove to member states and EU companies that it can be trusted to keep sensitive information safe.

The EU’s economic security agenda focuses on four categories of risks (technology leakage, critical infrastructure vulnerabilities, economic coercion, and supply chain resilience), with supply chain resilience presenting the greatest challenge in terms of developing credible policies.

While measures such as export control rules and foreign direct investment (FDI) screening regulations aim to mitigate technology leakage, initiatives like 5G security guidelines and the Cybersecurity Act aim to enhance European critical infrastructure against acts of hostility.

Additionally, the EU has passed an anti-coercion instrument to facilitate coordinated responses in case of targeting of EU member states or European companies.

Going at it alone

However, the effectiveness of these measures relies on their implementation by Member States and constant improvements to address loopholes.

In contrast, initiatives to enhance supply chain resilience at the EU level have been lacking. While a Critical Raw Materials Act is pending adoption, its focus on reducing European dependencies and streamlining administrative procedures falls short of addressing the magnitude of the challenge.

Member states are pursuing individual strategies. Germany has earmarked €1 billion for the acquisition of minority stakes in extraction, processing and recycling projects. The German Economy Ministry has also set up a raw material procurement unit internally.

The plan France 2030 supports lithium projects extraction and refining projects in France along with other private recycling initiatives, backed by €1 billion of public investment.

Italy is creating a “Made in Italy” fund, initially endowed with €1.1 billion, to support domestic projects.

In 2022, Poland has adopted a national raw materials policy, geared towards exploration and extraction of domestic resources.

Since June 2023, cooperation between France, Germany and Italy has been taking off to ensure smooth coordination of strategic projects.

Meanwhile, the private sector has taken many proactive steps to de-risk supply chains. Recent data compiled by the EU Chamber of Commerce shows that 18% of European companies have already transferred their investments out of China or are in the process of preparing to do so and that 22% are considering other countries for future investments that were originally planned with China.

For the private sector, de-risking is also a market opportunity: Companies trust consultancies to identify the weak points in their networks of suppliers, and software suppliers to optimise their supply chain’s organisation.

EU institutions, untrusted

However, reluctance to share sensitive information with the EU persists due to concerns over information security and a lack of trust in European institutions.

There are constant leaks to the media, which make the Commission one of the most transparent executive branches in the world.

There are concerns regarding its information system – its vulnerabilities to cyberattacks from hostile states, commercial spyware and to the US Cloud Act. And there are also frequent stories of weak links among member states.

Distrust impedes collective action, as evidenced by the struggles of initiatives like the European Semiconductor Board to facilitate public-private collaboration. Created by the EU Chips Act, the Board aimed precisely at information sharing between companies, member states and the European Commission.

It is by design that European institutions are incapable of sharing and centralising information. Each Directorate-General responsible for implementing economic security instruments operates independently, leading to the isolation of intelligence within confidential databases.

Article 10 of the FDI screening regulation specifies that “information received as a result of the application of this Regulation shall be used only for the purpose for which it was requested”. This standard formulation is used in the anti-subsidy regulation (article 29), the international procurement instrument, etc… Each instrument contains similar language.

European Commission must enter game of information superiority

Ultimately, despite the wealth of strategic information collected, stringent regulations prevent centralised aggregation and perpetuate the Commission’s limited role in supply chain security.

Of course, distrust towards European institutions does not explain everything. Companies are reluctant to share supply chain information because they understandably do not want their competitors to uncover their weaknesses or expose their suppliers to the highest bidders.

All global powers leverage economic intelligence to enhance competitiveness and national security. China has an obsession with information superiority. The US export licensing system serves as a significant intelligence-gathering mechanism, providing valuable insights into strategic sectors.

The European Commission must stop ignoring the economic intelligence game all powers are playing and develop a vision of information superiority.

If only one entity within the Commission could pool together all the economic intelligence collected by the EU’s economic security instruments, assuming that this entity had world-class analytical and cyber-defence capabilities, it would instantly become an indispensable asset for member states and private actors.

How to get there? Strengthening the EU’s economic security agenda requires removing internal barriers to information sharing and organising open-source economic intelligence collection on a large scale.

The EU Intelligence and Situation Centre (EU INTCEN), which organises intelligence sharing among member states (on a voluntary basis and on a very limited scale), is unlikely to be the right place to start.

What is needed is to exploit the rich data generated by the EU’s various economic security instruments, all located in other directorates of the Commission.

This task is essential to bolster Europe’s resilience in a world characterized by weaponized dependencies and competition for technological superiority. The next European leadership should consider this a priority.