Jonathan Portes provides a short write-up of his insights on the latest migration statistics released by the ONS through to June 2023.

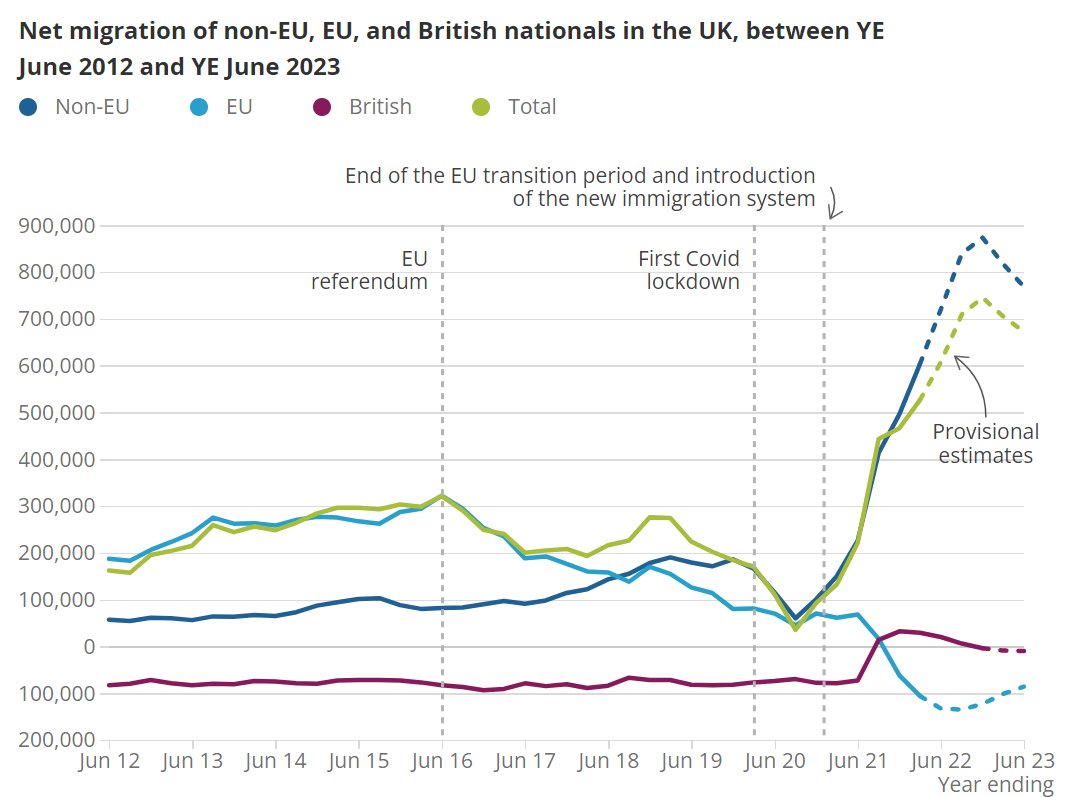

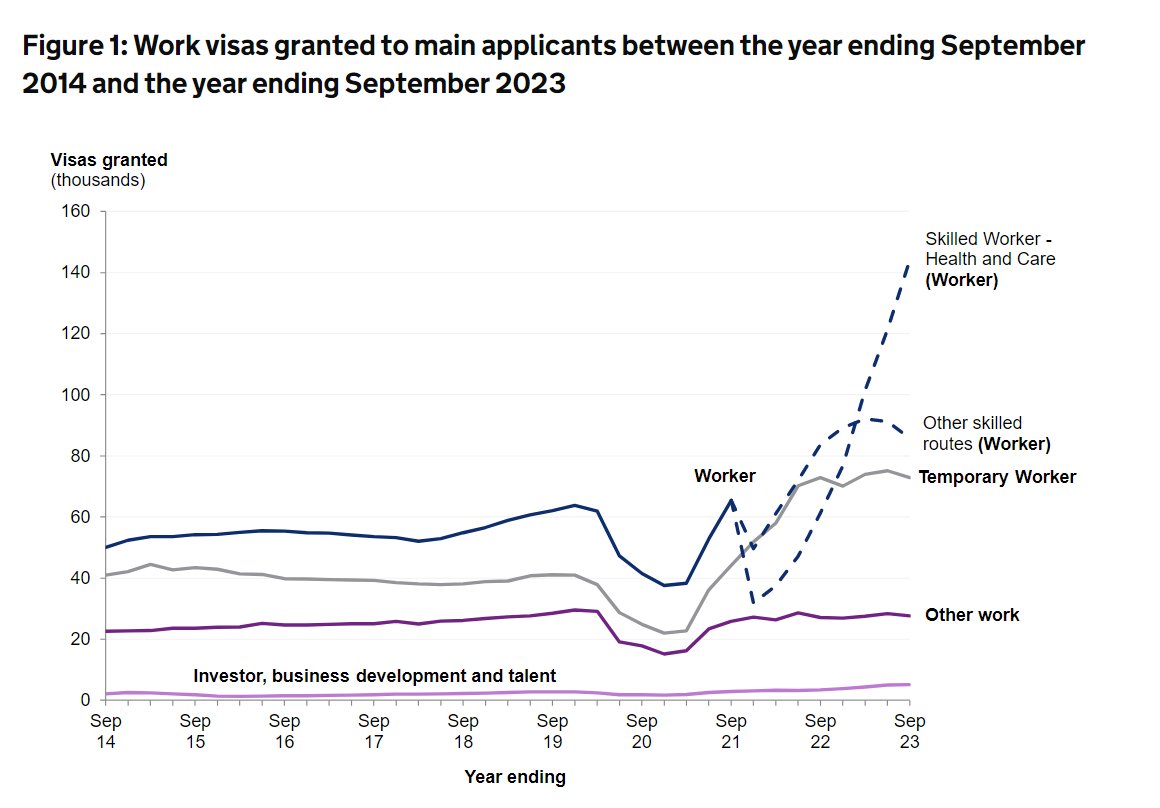

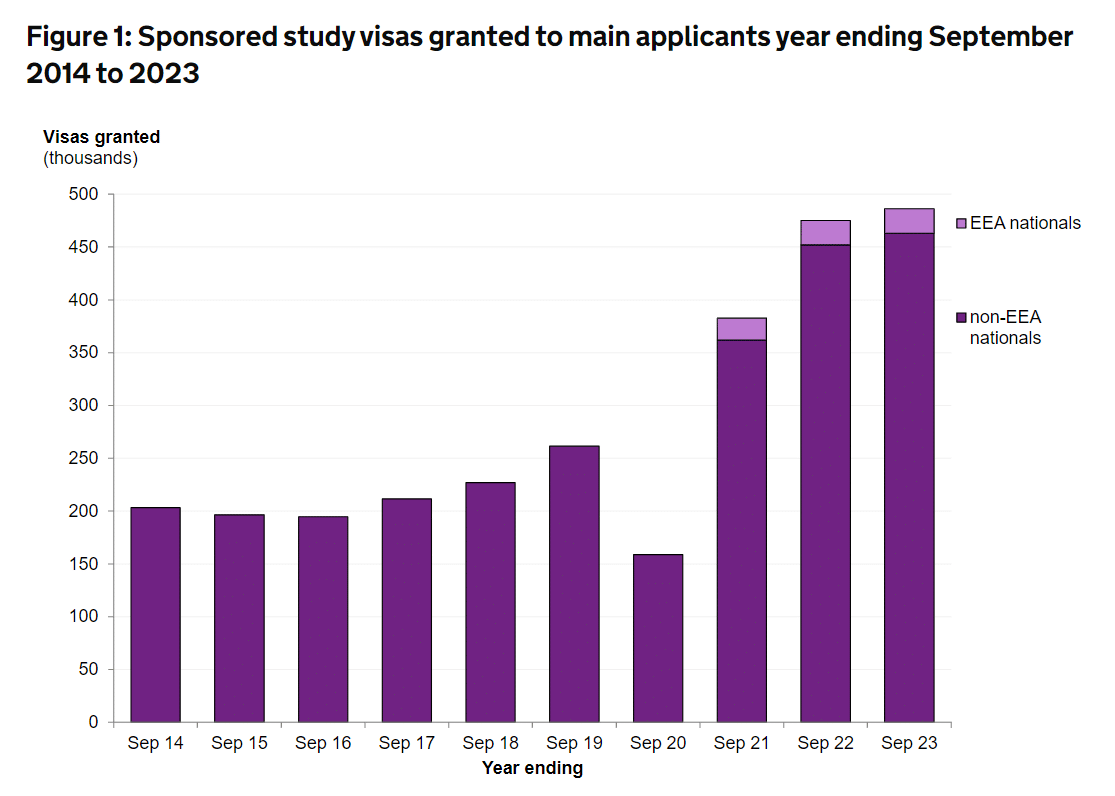

The first thing I want to highlight from today’s migration statistics is that while the release includes more revisions to previously published data by the ONS the big picture remains the same. Namely, the spike in migration post-pandemic was driven by increases in non-EU migration for work (especially health and care workers), students coming to study, the new schemes that were opened for British Nationals (Overseas) arriving from Hong Kong and the scheme for Ukraine, and lastly asylum seekers.

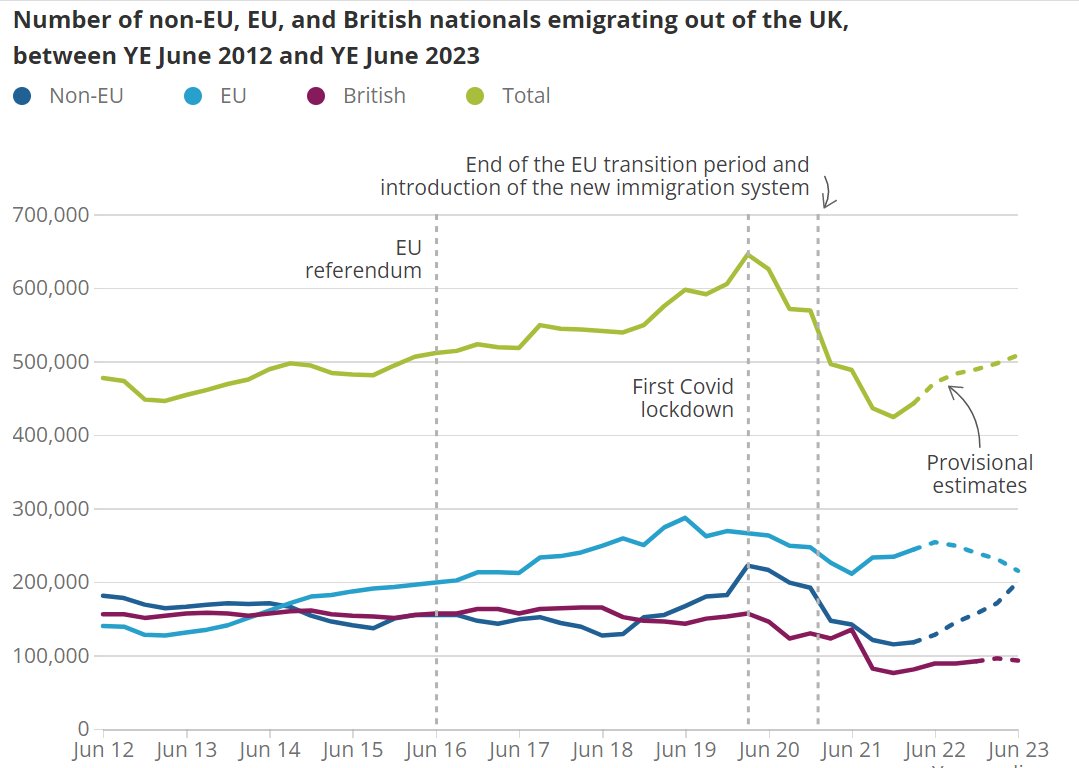

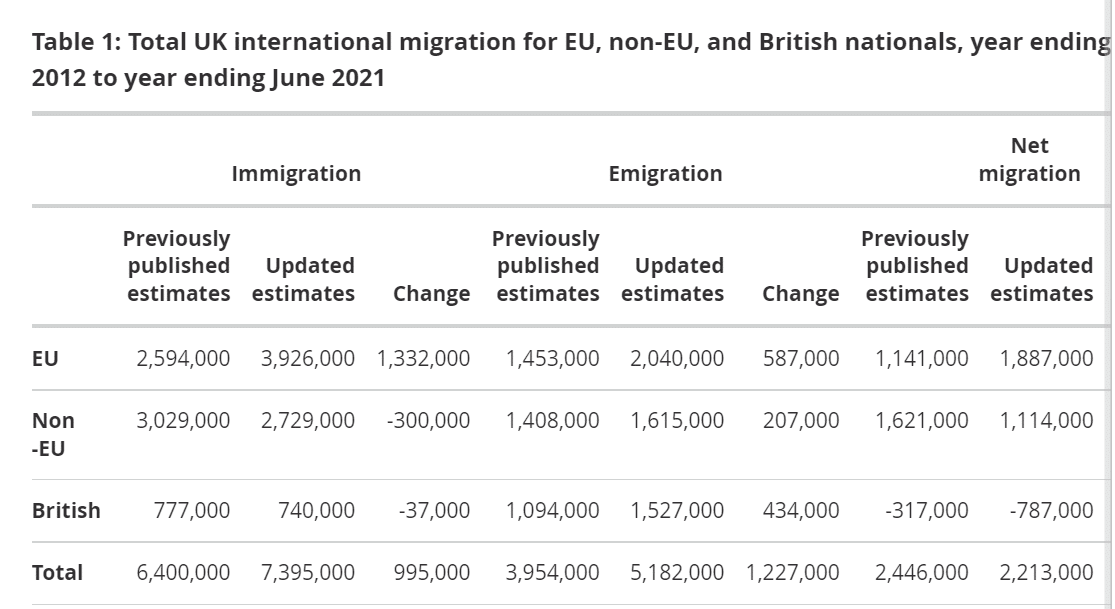

However, inflows have now peaked, and emigration is now increasing. This is a natural consequence of recent inflows, especially students who make up 39% of non-EU long-term immigration. Therefore, more recent immigration => more emigration. So, emigration will continue to increase, reducing net migration. In addition, we may be underestimating emigration – as the very large downward revision to net non-EU migration over the 2011-2021 period shows (see below).

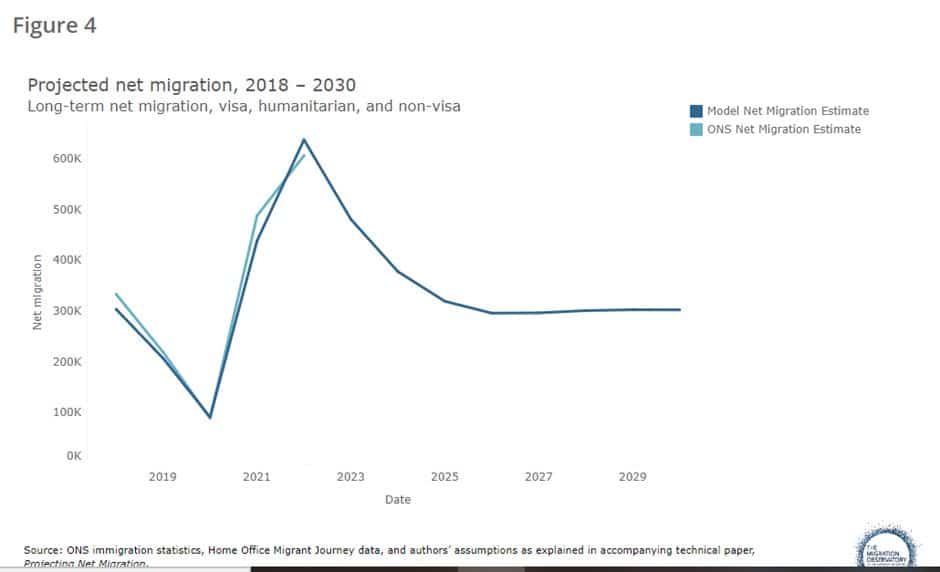

The Migration Observatory think this means long-run ‘equilibrium’ levels of migration might therefore settle around 300K. Today’s stats don’t really change that much. Obviously, there’s huge uncertainty here, both about policy, the economy/labour market, and migration trends.

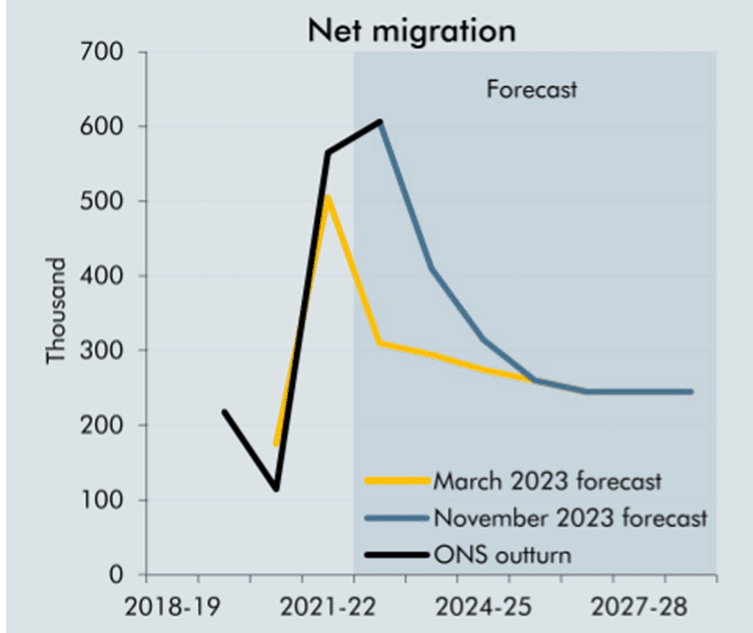

This is also what the OBR assumed yesterday – a pretty sharp fallback in net migration to a long-run level much lower than today. Again, today’s stats won’t change that much.

More recent visa statistics also show some fall in inflows for work, reflecting softening in the labour market, with the exception of health and social care workers.

Similarly, student visas seem to have stabilised at a high level – but student net migration seems certain to fall quite sharply now for the reasons above.

What does this mean for the economy? Over the last 2 years, upward revisions to the OBR’s migration assumptions have added perhaps 1.5% to forecasts for the size of the labour force, GDP (£40 billion) and tax revenues (£18 billion). This is not a small change.

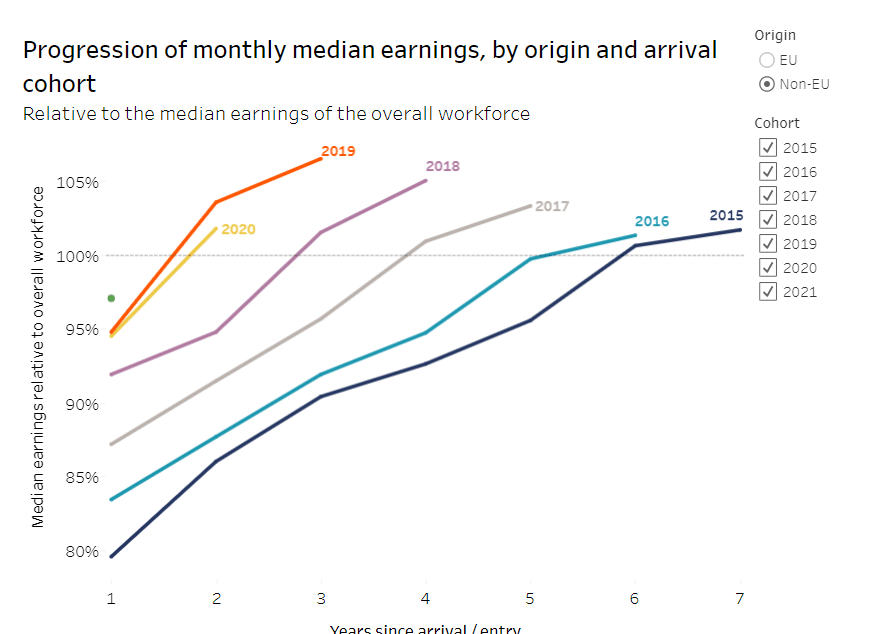

In some respects, this may be too pessimistic – recent migrants, especially from outside the EU, seem to have relatively high earnings.

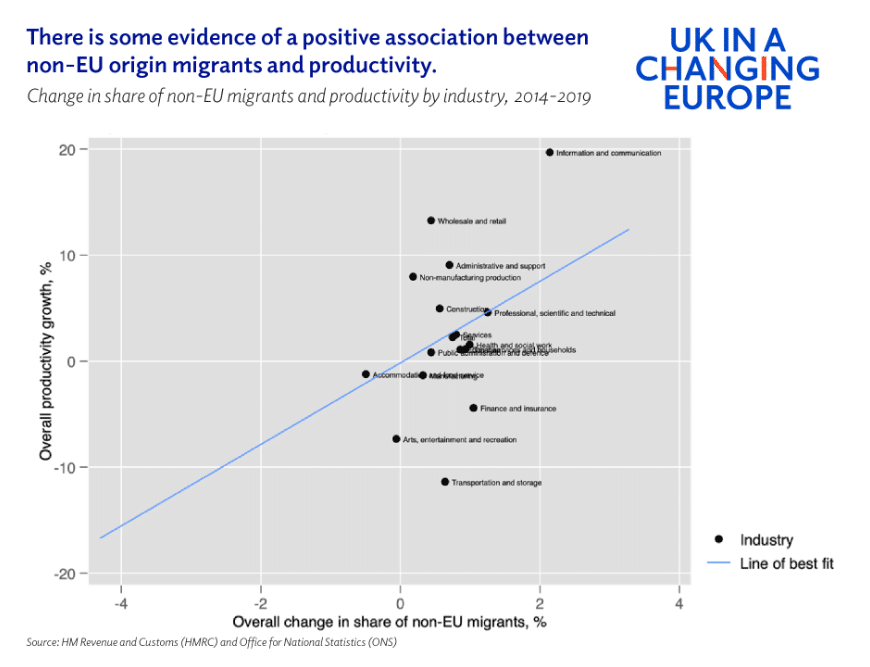

And even more important high non-EU migration seems to be positively associated with productivity.

But of course, more migration adds to pressures on public spending. The OBR doesn’t take that into account. This should not be seen as their fault. It’s just another aspect of the government’s wholly unrealistic assumptions for public spending used to justify tax cuts.

The OBR explained that these assumptions would leave other ‘unprotected RDEL [resource department expenditure limits] spending needing to fall by 2.3% a year in real terms from 2025-26’. They continue that if defence and official development assistance (ODA) spending were to increase in line with what the government has outlined as its ambitions it would ‘lead to unprotected spending needing to fall by an average of 4.1% a year’. 2.3% is already seen as a challenge that would strain public services.

So, while Neil O’Brien makes some very reasonable points here, his criticism of the OBR on the central point is misplaced. The OBR has no choice but to believe what some see as the government’s entirely fictional numbers for future spending.

The most interesting figures today aren’t any of the new figures but the revisions to 2012-21 reflecting the Census. ONS now says that non-EU net migration was overestimated by 500,000, EU net migration was underestimated by 750,000, and net emigration of British nationals was underestimated by 570,000.

There is a lot more in the detailed data tables to look at a future time. But, once again, in a rational world, this is (mostly) good news for the UK – a rare economy/Brexit good news story.

By Professor Jonathan Portes, Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe.