The Office for National Statistics recently released fresh data on the UK’s labour market, inflation and GDP. While trends in prices and wages have improved conditions for many households, the economy has contracted since early 2022. Prospects for renewed growth are positive but weak.

Earlier this month, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) released new data on the UK labour market, inflation and economic growth. Taken together, these data provide a number of insights into the current state of the economy.

Labour market

On 13 February, the ONS released new UK labour market data. These figures relate to measures such as average weekly earnings and the number of people in employment. There are three notable points to highlight:

- Average earnings grew at a slower pace at the end of 2023 relative to the record annual growth rates observed over the summer, but earnings growth remains high by historical standards.

- Workers have only started to see their earnings grow in inflation-adjusted terms since the summer, following around two years of wage erosion as a result of inflation.

- An increase in people not participating in the labour force because they are long-term sick remains a serious challenge.

The annual growth rate of average weekly earnings (excluding bonuses) from the final quarter of 2022 to the third quarter of 2023 was 6.2%. This rate has been on a decreasing trend since peaking at 7.9% in August 2023. That said, it remains well above its series average of 3.2%.

Economists call earnings that are adjusted to reflect the current rate of inflation ‘real earnings’. This term can help us to capture the fact that if wages fail to match price rises, households are materially worse off. When we adjust for inflation, the annual growth rate of average weekly earnings (including bonuses) falls from 5.8% to 1.4% in the final quarter of 2023, indicating the extent to which rising prices continue to erode people’s pay.

As Figure 1 shows, most workers saw their real incomes contract throughout 2022 and into 2023, until high wage growth in the summer of 2023 (including one-off payments, such as civil service bonuses) pushed the annual growth rate of real total average weekly earnings into positive territory. We can think of high wage growth in 2023 and the expected high wage growth in 2024 as necessary for workers’ real wages to catch up to where they might have been prior to the cost of living crisis.

Figure 1: Real average weekly earnings (including bonuses)

Source: ONS, author’s calculations

The latest data release also marked the first time since October 2023 that the ONS released updates from their Labour Force Survey (LFS). The delay in updates was due to issues surrounding LFS data, as described in NIESR’s latest Wage Tracker.

The LFS gathers information from households to construct key labour market measures such as employment, unemployment and economic inactivity (used to describe people that are not part of the labour force because they are not in employment and are not currently looking for work). This information is central for understanding the state of the labour market.

Most importantly, the newly updated LFS data tell us that the number of people economically inactive increased significantly in 2023. In part, this reflects updates to estimates of the UK population. For example, in the latest population estimates, there are more people aged 16-24 and more women than previously thought. These are two groups that tend to have higher rates of economic inactivity.

But when we look at data that breaks down economic inactivity by reason, we can see that the main driver of recent increases in inactivity has been an increase in people reporting that they are long-term sick (see Figure 2). Addressing this challenge requires targeted policy interventions, such as reducing NHS waiting lists. After all, maintaining a healthy labour market requires a healthy working population.

Figure 2: Cumulative change in economic inactivity by reason since Covid-19

Source: ONS, author’s calculations

Notes: The data after July-September 2022 have been reweighted, causing a step change discontinuity. For more information, see the ONS update on LFS reweighting.

Inflation

The ONS produces a particular measure of inflation based on a consumer price index (CPI). CPI, described in further detail in this blog, is used to measure how quickly the prices of goods and services bought by households are rising. The latest ONS data release indicates that annual UK CPI inflation was 4% in January, unchanged from December 2023. This means that the average prices in an average household’s spending ‘basket’ in January 2024 were 4% higher than those in January 2023.

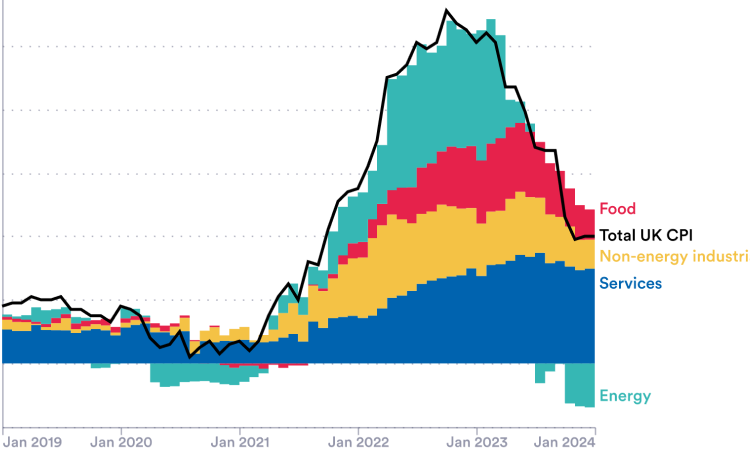

Turning to the underlying products and services that make up the basket, Figure 3 illustrates how the contributions of different components to CPI inflation have changed in the past few years. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, energy price increases contributed significantly to rising CPI inflation. But since the second half of 2023, these energy price increases have been dropping out of the CPI basket, and that has contributed to driving down inflation, alongside an easing of inflation rates in food and non-energy goods.

Figure 3: Contributions of components to annual CPI inflation

Source: ONS, author’s calculations

The January inflation data are surprising. NIESR’s most recent UK Economic Outlook had forecast a rise in CPI inflation in January relative to December. But as described in the Outlook, it is believed that CPI inflation will continue to fall throughout the rest of the first half of 2024, as energy prices continue to fall (and contribute negatively to CPI).

So, this recent downward surprise may signal that inflation is set to fall even faster in the coming months than first projected. If true, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) may start to cut interest rates (which currently stand at 5.25%) in the spring.

But energy prices aren’t the whole story. The data also suggest that there are certain risks to inflation that might render it higher than expected in the coming months (also known as ‘upside risks’). For example, inflation in services has averaged around 6-7% since the second half of 2022, and this figure rose slightly from 6.4% in December to 6.5% in January. This is relevant because services inflation mostly reflects domestic price pressures (in particular, wages in the services sector) rather than external factors (like energy or food import prices).

Services inflation can reveal something about underlying domestic price pressures. That it remains so high – and contributed around three-quarters of the total annual CPI rate in January 2024 (see Figure 3) – indicates that underlying domestic inflationary pressures are an important upside risk to CPI inflation over the coming months. So, in terms of price growth, the UK is not out of the woods yet.

In NIESR’s recent UK Economic Outlook, we note that the MPC will not want to lower interest rates prematurely and then have to raise them again. So, while the recent data signal that inflation may fall faster than expected in 2024 and that we might see interest rates fall soon, it is likely that some caution will be exercised by the MPC in this respect.

Gross domestic product (GDP)

Most significantly, the 15 February ONS data on gross domestic product (GDP) tell us that the economy has not grown since 2022 (see Figure 4) The analysis below builds on a previous Economic Observatory article, which explains what GDP is and how to interpret GDP data.

Figure 4: Monthly GDP growth index

Sources: ONS, NIESR calculations

Monthly GDP fell by 0.1% in December 2023, following growth of 0.2% in November. This figure was driven mainly by decreasing output in the services sectors, particularly in the wholesale and retail trade category, as well as the construction sector.

Looking at the broader picture, GDP contracted by 0.3% in the final quarter of 2023, relative to the previous three-month period. This was caused by contractions in all the main sectors: in the final quarter of 2023, services output fell by 0.2%, production output fell by 1% and construction output fell by 1.3%.

The data for the fourth quarter of 2023 mark two quarterly consecutive falls in GDP, following a fall in GDP by 0.1% in the third quarter of 2023. By the standard metric, this means that the UK economy was in a shallow recession in the second half of last year. But as argued in NIESR’s GDP Tracker, whether the economy was in a ‘technical recession’ (two consecutive periods of negative growth) in 2023 is largely beside the point.

The technical recession metric is arbitrary and not greatly informative. The state of UK economic growth is better described by the fact that GDP growth has been near zero since early 2022 (see Figure 4). In fact, GDP fell between the first quarter of 2022 and the final quarter of 2023.

What’s more, GDP per head remains lower than before Covid-19 – which means that one measure of our living standards is worse now than it was prior to the pandemic. This should be of more concern than whether growth in the last two quarters was just below zero.

Yet, in NIESR’s recent UK Economic Outlook, we project that despite economic growth being subdued in 2023, GDP will grow by 0.9% in 2024. This forecast is quite low by historical standards, and it is expected to remain around the 0.9% figure for the next few years, unless policies are implemented to boost growth, such as increased public investment.

Still, it is not all doom and gloom: low growth is still growth – and better than a sustained flatlining of the economy.

Conclusion

Taken together, the latest data tell us a fair amount about the current state of the UK economy.

The good news is that workers are finally seeing their real incomes grow; CPI inflation is on a downward trend and likely to fall to, or below, the Bank of England’s target of 2% a year in the coming months; and the economy will probably grow somewhat in 2024.

That said, many challenges remain. In particular, targeted interventions are needed to reduce long-term sickness in the UK; upside risks to inflation may require the MPC to exercise caution in cutting interest rates, which might have adverse effects on interest-sensitive sectors and mortgage holders; and large reforms, such as an increase in public investment, will be needed to escape the current low growth trend that threatens to reduce UK living standards even further.

Where can I find out more?

- For a comprehensive analysis of the state of the UK economy, read NIESR’s most recent quarterly UK Economic Outlook here.

- The NIESR Wage, CPI and GDP Trackers are available here.

- The ONS bulletins on the labour market, CPI inflation and GDP.

Who are experts on this question?

- Jagjit Chadha

- Huw Dixon

- Stephen Millard

- Jonathan Wadsworth