Stephen Hunsaker takes stock of UK-EU trade in 2023, the first post-Brexit year not significantly impacted by Covid-19 or the energy crisis. He highlights that while the share of UK trade with the EU trade grew in 2023 this is largely due to a fall in the share of non-EU trade –particularly with China and Norway.

2023 was a perplexing year for UK trade. It marked the third year post-Brexit and the first year not significantly impacted by Covid, the energy crisis, or inflation. So, what did we learn about the UK’s trade relationships in this true post-Brexit year?

One of the most notable findings is that the UK’s trade ties with the EU look surprisingly strong. The same cannot be said of non-EU countries, whose share of total UK trade was down. This has confounded trade economists and made them reassess their expectations of post-Brexit trade.

It is worth reflecting on the expectations of Brexit. Most economists predicted that exiting the single market and customs union would have a significant negative impact on UK trade. They also believed that the new post-Brexit freedom to conclude new trade deals would only partially mitigate this effect in the short- to medium-term.

For instance, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimated that Brexit would reduce UK trade by approximately 15%. They also stated that new trade deals were unlikely to have ‘a material impact’ on economic growth. For example, the only two new deals signed with Australia and New Zealand are projected to increase GDP by just 0.08% and 0.03%, respectively.

However, these models did not anticipate a scenario where trade with the EU remained relatively stable, while trade with non-EU countries not only failed to grow but shrank.

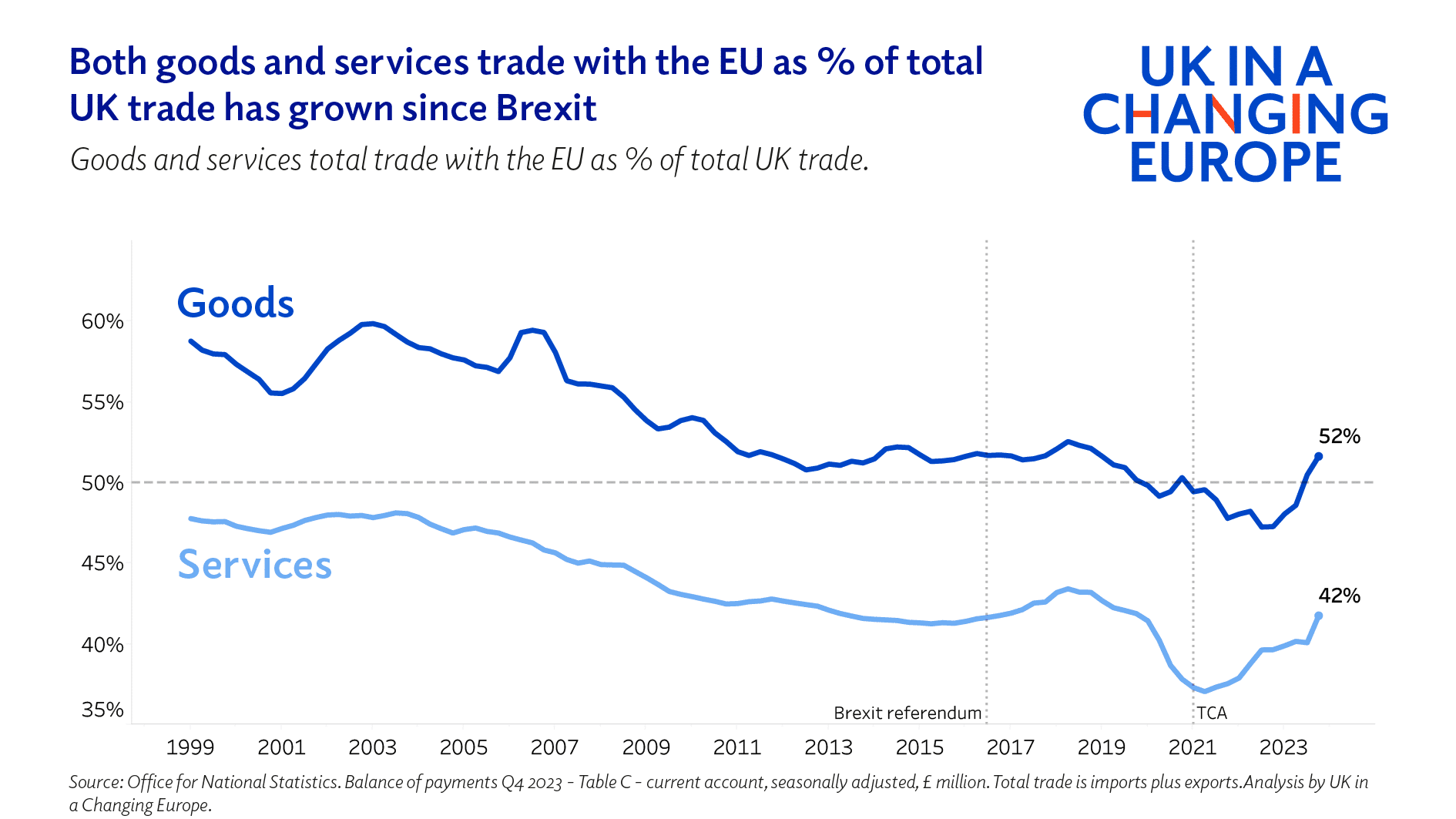

The chart above clearly illustrates that the EU’s share of total UK trade in goods and services significantly declined in the lead-up to the end of the Brexit transition period. However, in 2023, both EU goods and services rebounded, with EU goods now comprising 52% of total UK goods trade.

This might appear as if trade with the EU dramatically increased in 2023. However, the real reason is that trade with non-EU countries fell at such a rate that the EU reclaimed a majority share of total trade.

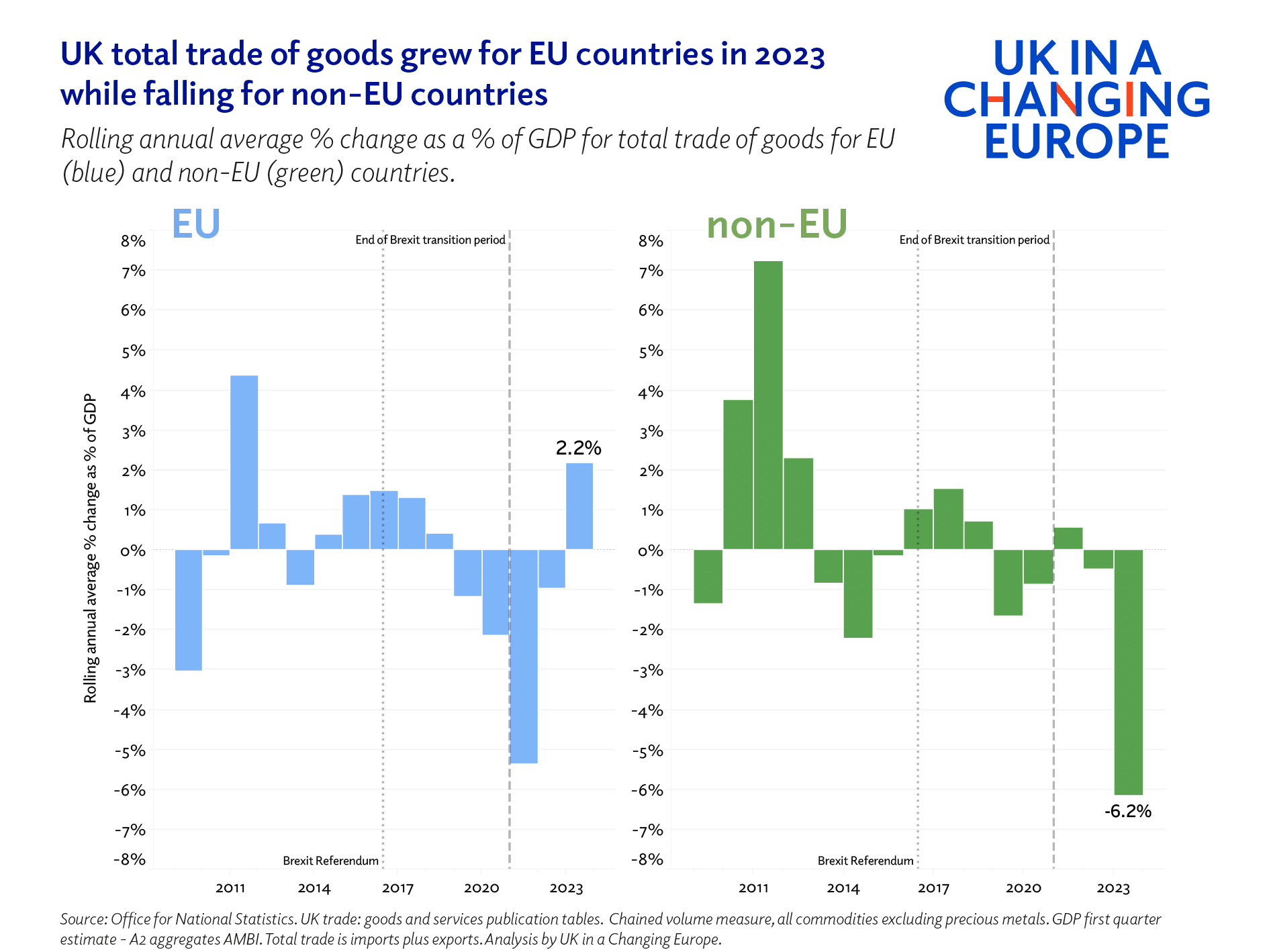

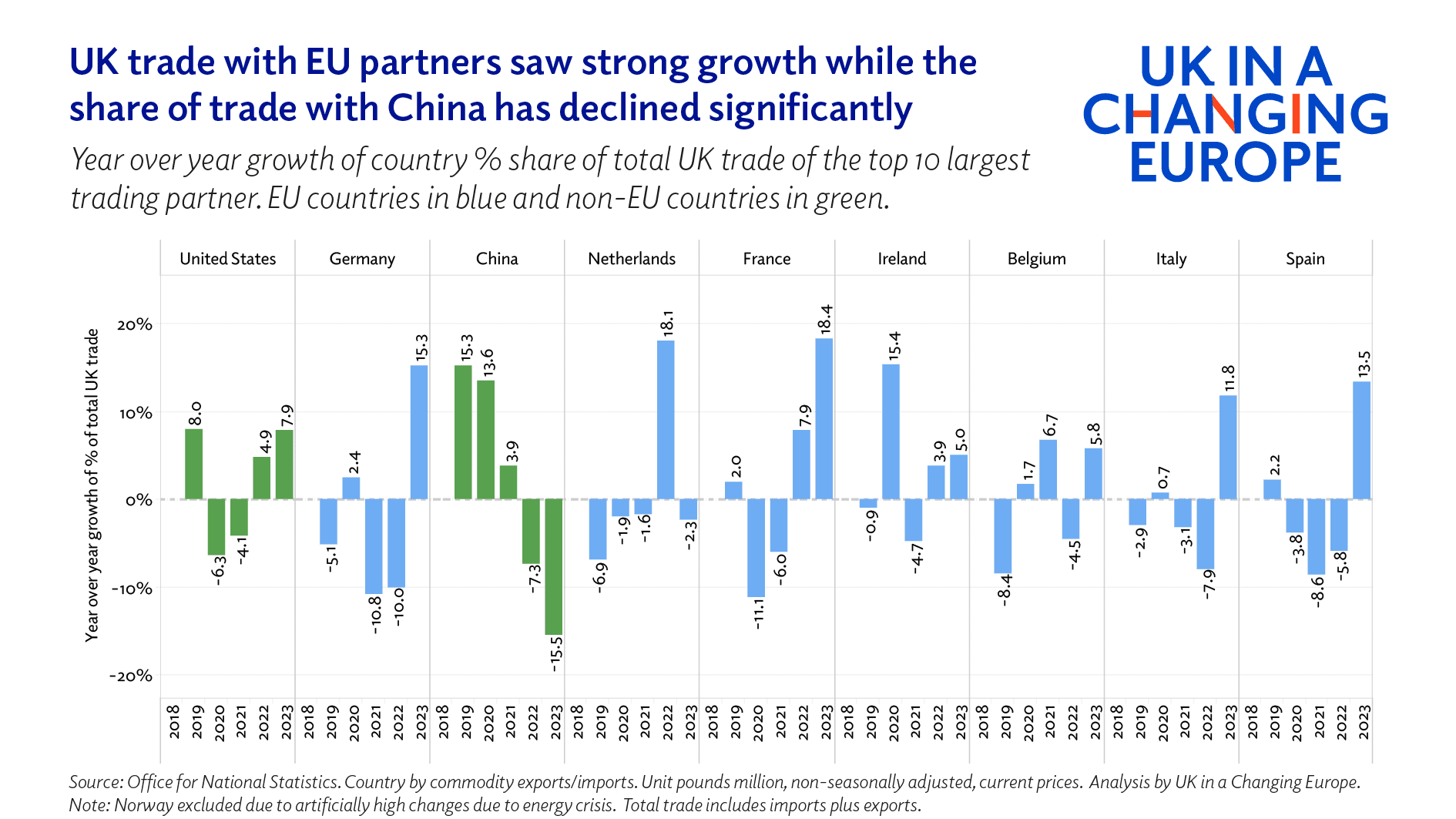

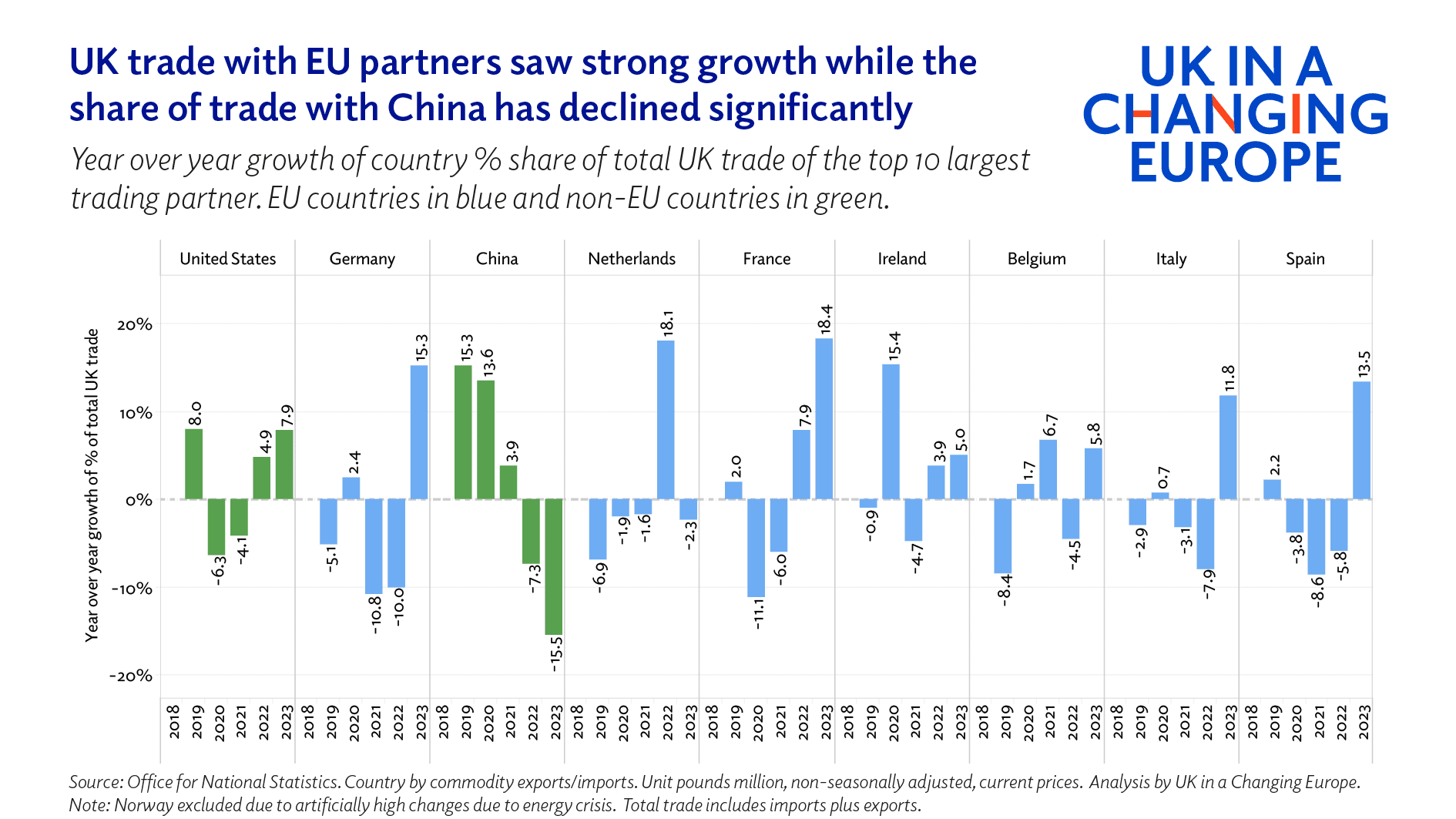

Similar to the share of total trade, EU goods as a percentage of GDP suffered in the lead-up to and especially during 2021 when the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the EU was implemented. While the TCA did not impose tariffs between the UK and EU, it did introduce non-tariff barriers such as new paperwork. However, the data shows that trade flows between the UK and EU for goods grew in 2023 at a healthy rate of 2.2% compared to 2022. That was not the case for non-EU countries. While the UK saw a modest increase in trade year-over-year in 2021, trade flows significantly declined in 2023, with trade with non-EU countries declining by 6.2% compared to 2022.

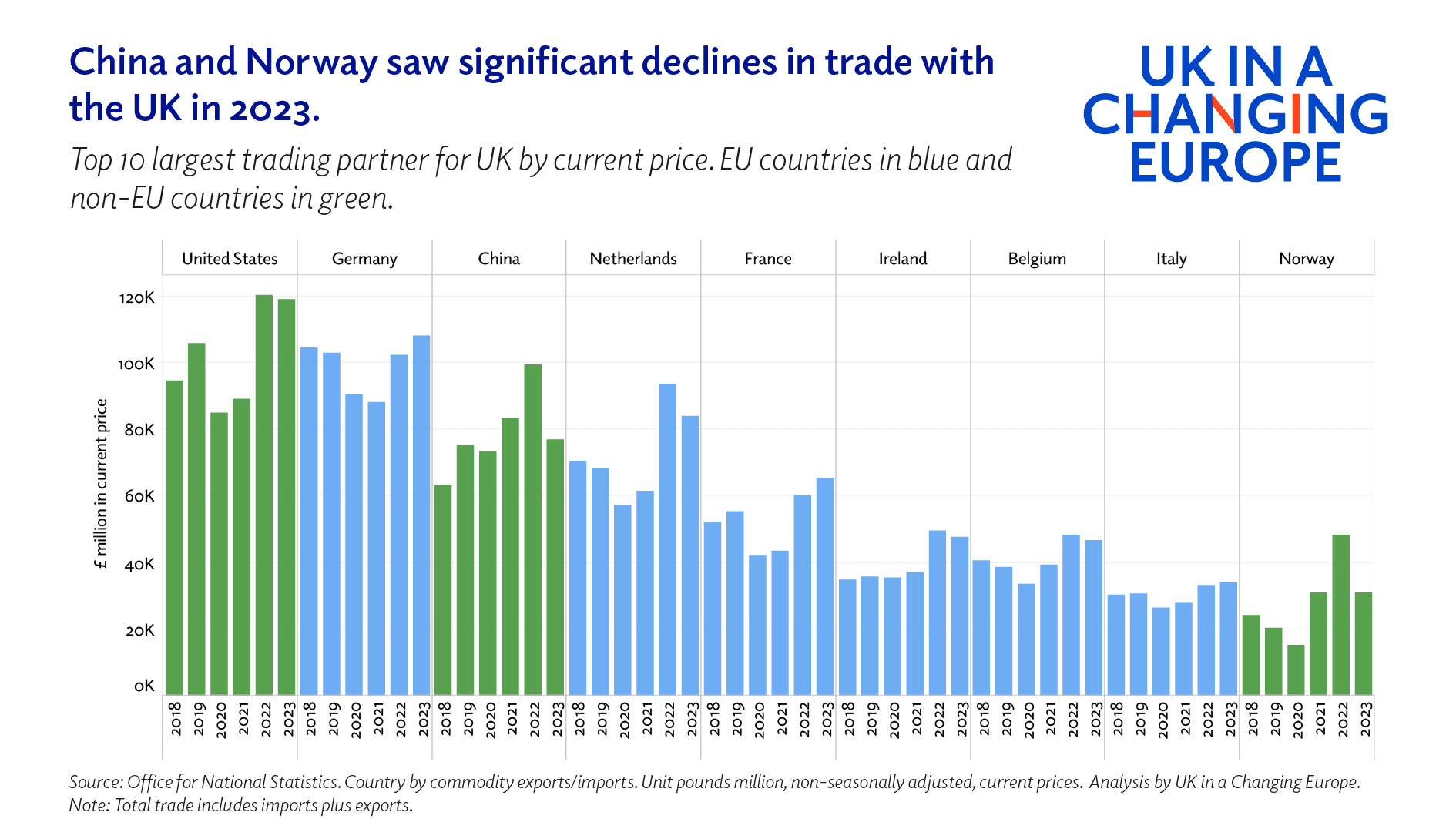

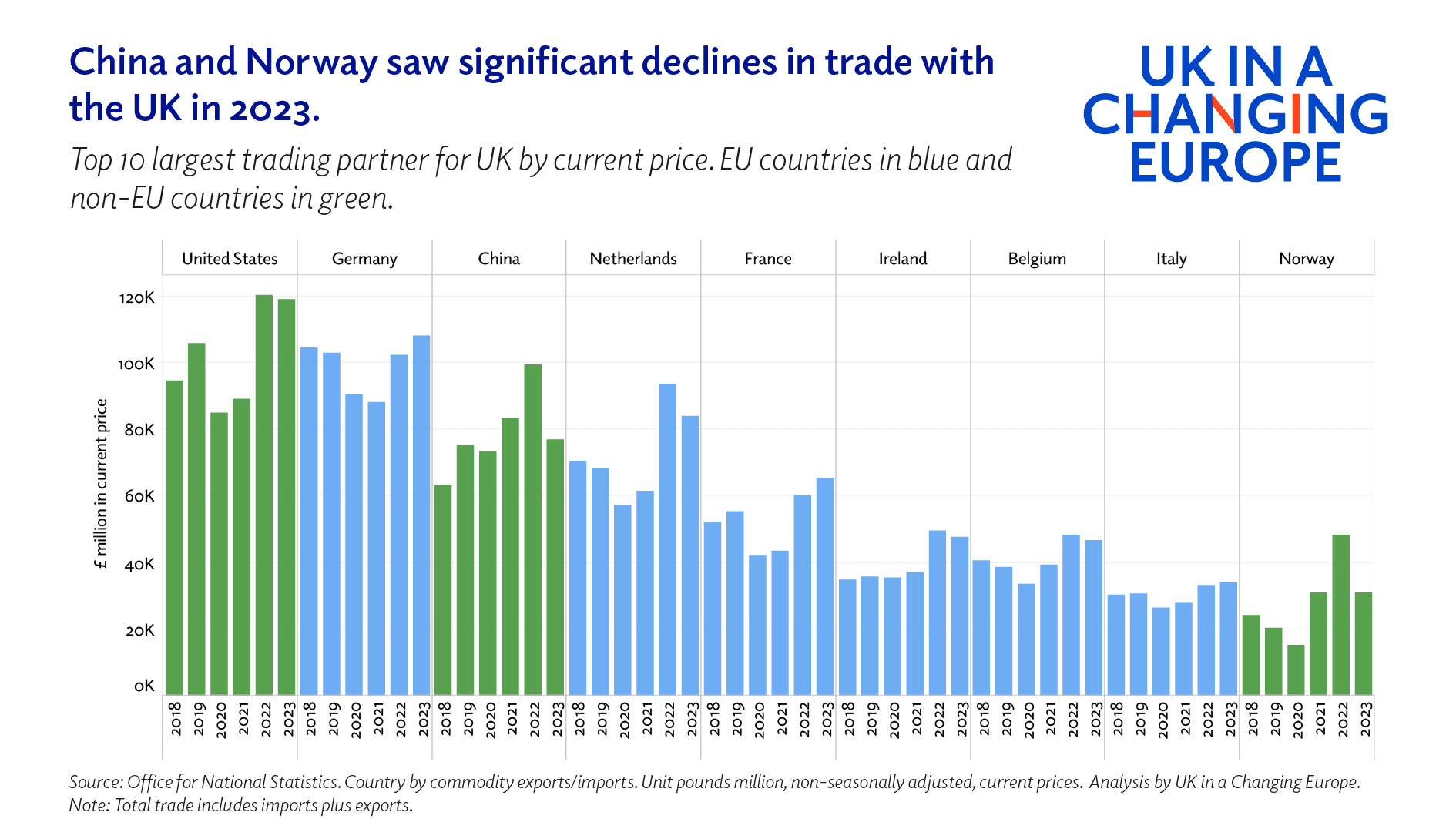

What caused this decline? There appear to be two main factors: China and Norway. In the case of China, geopolitical tensions are the main factor. After the referendum, the Conservative party aimed to increase trade with China, viewing it as a crucial trade partner in a post-Brexit ‘Global Britain.’ However, the war in Ukraine and pressure from allies to derisk supply chains pushed the UK to distance itself, resulting in trade with China falling by 7% and 15% year-over-year, in 2022-2023.

In the case of Norway, this is a story of inflation. Trade with Norway skyrocketed in 2021, not due to increased trade volumes with the UK but soaring gas prices, spurred on by the war in the Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis. The UK paid significantly more for its gas while receiving the same amount in return.

Adding Norway to the chart significantly distorted it, requiring its exclusion to even see the changes for the other top 9 countries. The UK saw trade with Norway increase by nearly 86% in 2021 from the previous year, followed by a 22% increase from 2021 to 2022. In 2023, as inflation began to cool globally, gas prices fell back to normal levels, leading to a 30% decline in UK-Norway trade.

Looking at the rest of the UK’s top ten trading partners, of which eight are in the EU, EU countries all saw trade with the UK jump in 2022 but then stabilise in 2023.

This is why we can say that the surprising increase in the EU trade share in 2023 was in fact not due to strong growth of EU trade, but instead to a significant fall in non-EU trade.

But why has trade with the EU remained so stable? The TCA led to initial trepidation among EU trading partners, but businesses quickly adapted and continued as usual. However, there are two caveats. Large businesses adapted quickly, but small businesses have been disproportionally affected by the non-tariff barriers in the TCA. Yet, due to small businesses being just that, small, these impacts do not show up in administrative trade data.

Additionally, while businesses have maintained trade between the UK and EU, there has been no significant growth, businesses look focused on maintaining current trade flows but are not looking to grow them.

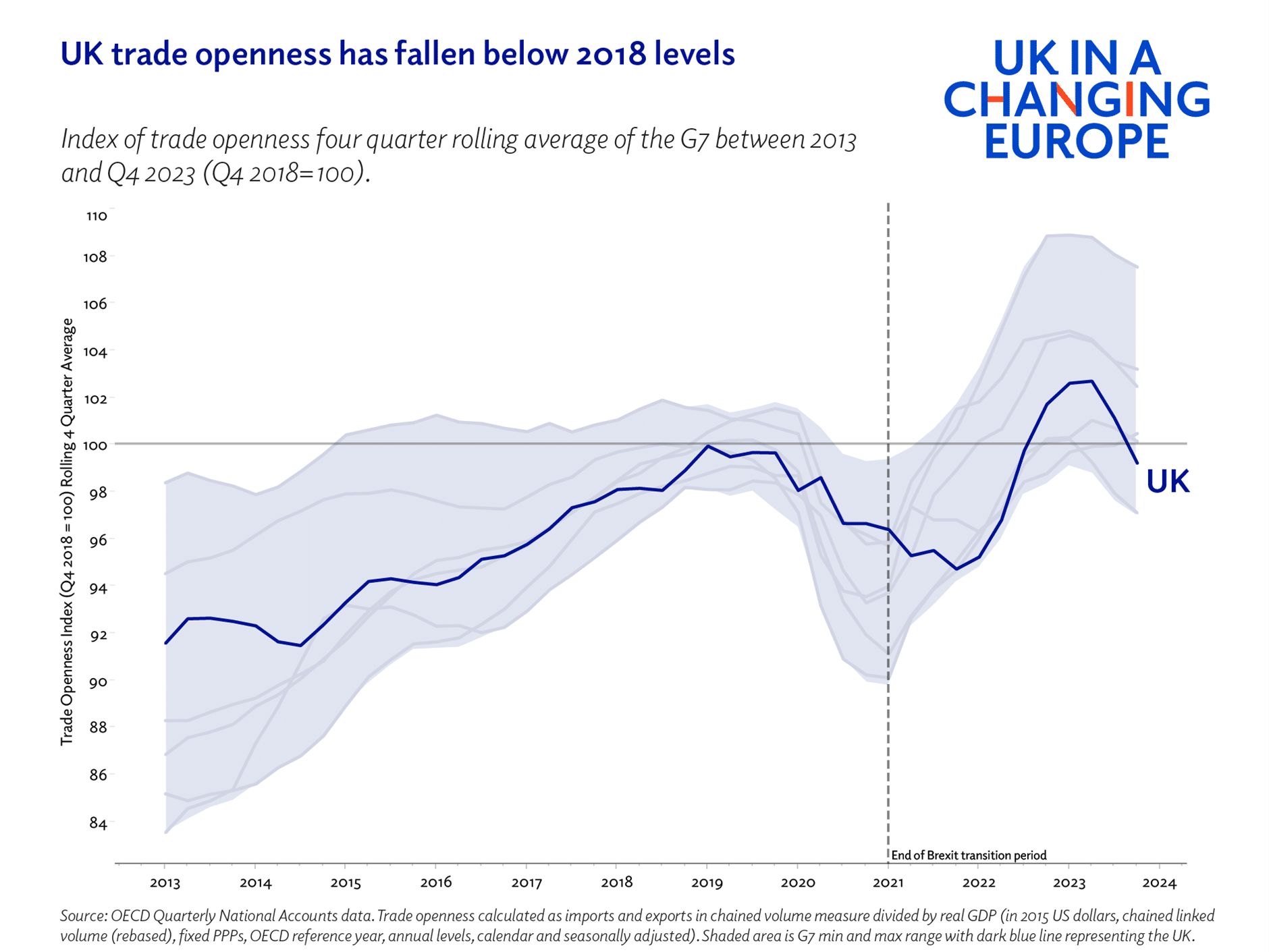

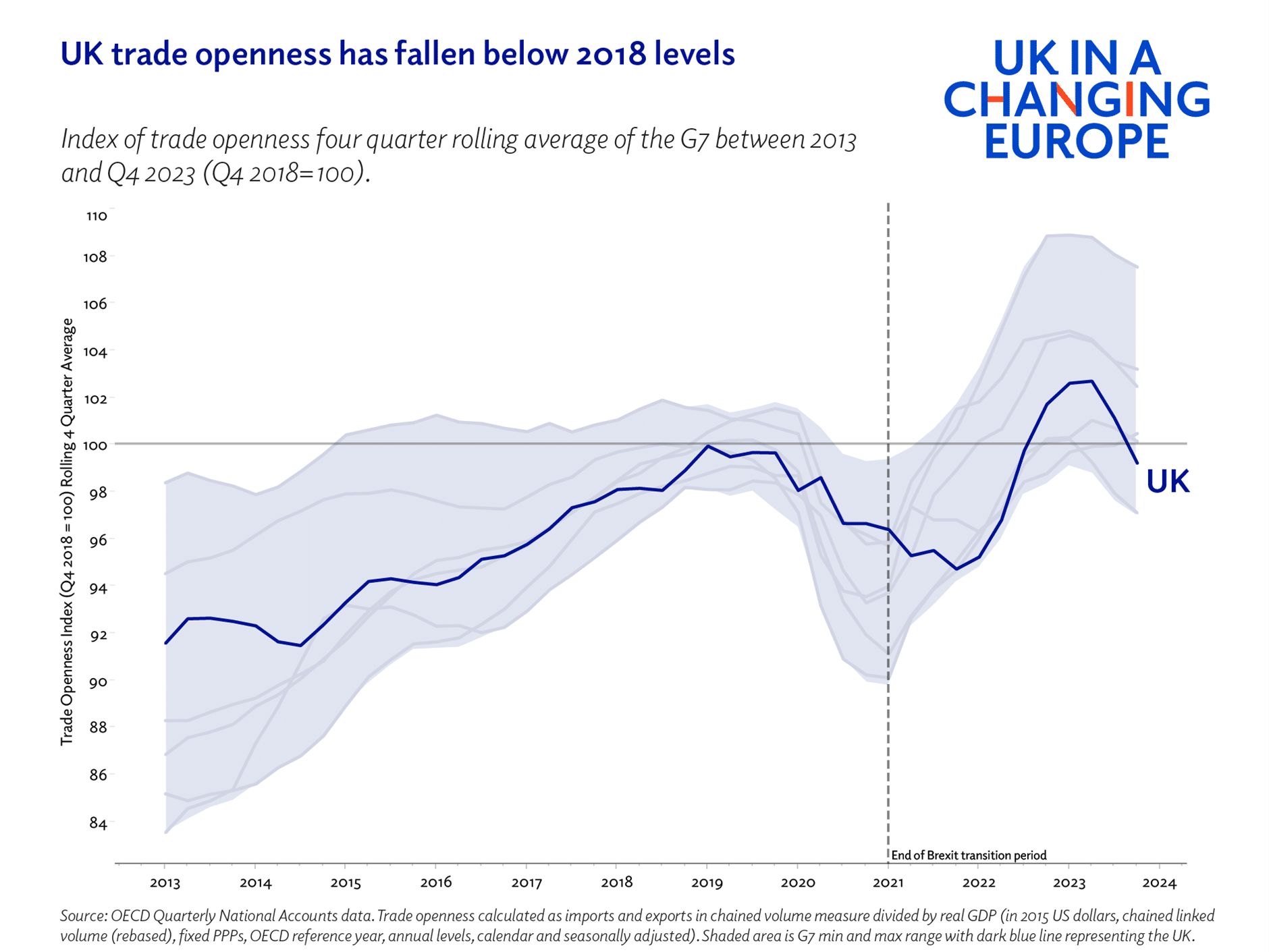

This maintenance of the status quo is what trade economists have termed the ‘slow puncture’. UK trade has not fallen off a cliff, but slowly declined or stagnated. This is a dangerous outcome, as it may allow politicians to believe that trade is normal due to the absence of massive fallouts. However, when UK trade is compared to its counterparts, it becomes clear that the UK is lagging behind.

In 2023, the UK’s post-Brexit trade landscape became clearer, and with that came many subverted expectations. However, what does seem to still ring true is the OBR’s prediction of trade in the long term being down 15% compared to if the UK had stayed in the EU. This ‘slow puncture’ effect hides deeper issues and must be acknowledged in any future trade strategies.

By Stephen Hunsaker, researcher, UK in a Changing Europe.