US economic re-acceleration or recession?

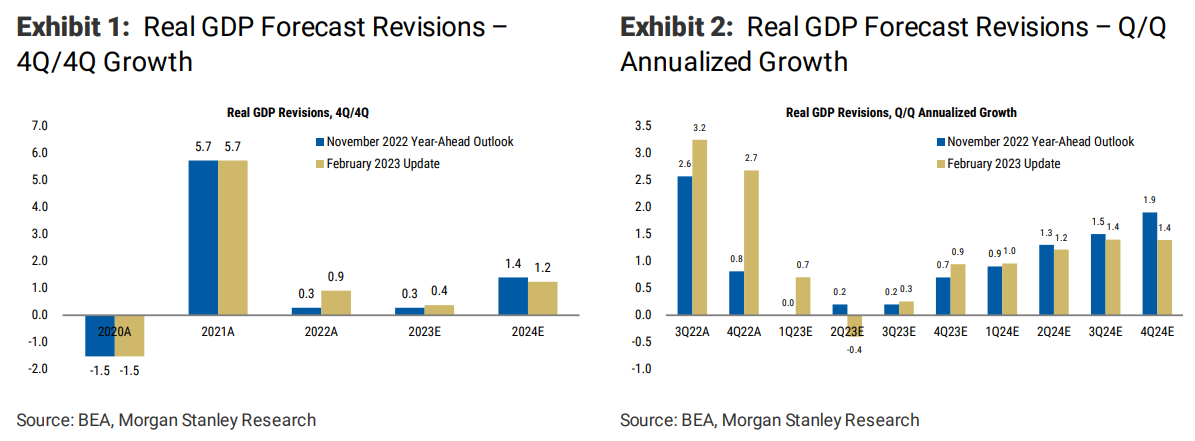

The US economy has been remarkably resilient, even as monetary tightening is working as intended. Labor market catch-up, excess savings, and lower energy prices are boosting the consumer, but a slowdown is still coming. We see the first cut delayed to March 2024, followed by more gradual easing.

Recession fears are turning into fear of re-acceleration: Against the backdrop of the fastest monetary policy tightening in recent history, the US economy has displayed remarkable levels of resilience. Investors have begun to interpret the lack of a clear and persistent slowing in the economic data in recent months as a sign that the economy has been less affected by monetary policy than initially expected.

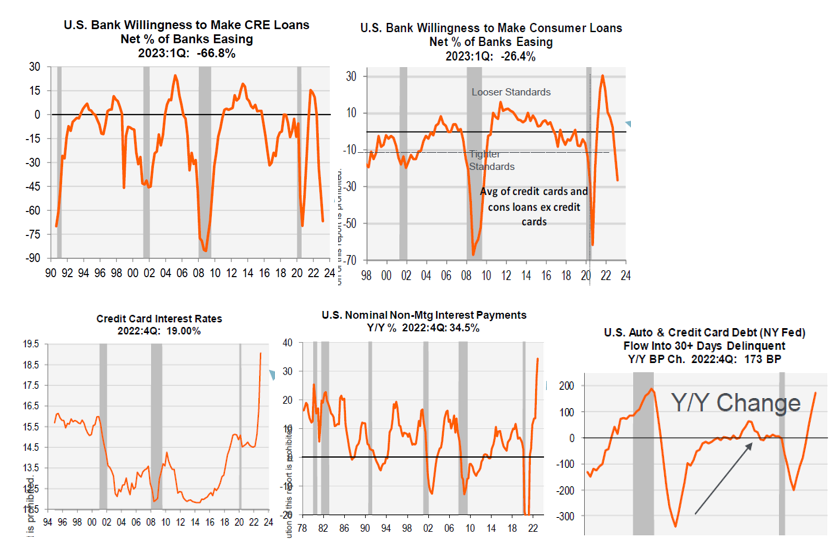

Aggregate activity has held up well, but under the hood, higher interest rates are clearly biting. Interest-sensitive parts of the economy have largely responded as expected. Housing activity responded immediately to higher interest rates, but declined significantly more than in prior cycles and what our models would imply. Consumer spending on durable goods has dampened as expected as well.

Instead, other factors have injected more strength into the economy than expected. Labor markets saw outsized hiring as companies caught up on significant staffing shortfalls faster. Households have spent down excess savings stocks at a rapid clip, supporting spending,and consumers saw their spending power boosted by declining energy prices just as monetary tightening began. Strong corporate earnings and healthy corporate balance sheets have also prevented a larger decline in business investment.

As these pillars of resilience fade over the coming months, economic slowdown should become more apparent. Staffing levels are closing in on levels more consistent with the level of economic output. Excess savings now look roughly normal for large parts of the population,and energy prices are unlikely to be a major boost for household spending in the months ahead. Residential investment activity and consumption growth should bottom mid-2023, while business investment deteriorates throughout our forecast horizon. Growth will remain below potential until the end of 2024 as rates move back toward neutral.

Even with more deceleration ahead, more resilience so far shifts out the policy path. We continue to expect the Fed to deliver a 25bp hike at both its March and May meetings, bringing the peak policy rate to 5.00% to 5.25%. However, with less and later of a slowdown in the labor market, the conditions for a first rate cut become less supportive,and with a more moderate increase in the unemployment rate, the pace of easing from there is likely also to be slower. Our read is that a longer hold period is preferred to a higher peak, since it carries less risk of overtightening.

We now see the Fed delivering the first rate cut in March 2024 (vs. December 2023 previously) and cutting rates at a slower pace of one 25bp cut each quarter. This brings the federal funds rate to 4.25% by the end of 2024. With rates well above neutral throughout the forecast horizon, growth remains below potential as well.

BofA’s credit card data presaged the January spending surge and now it is indicating the opposite.

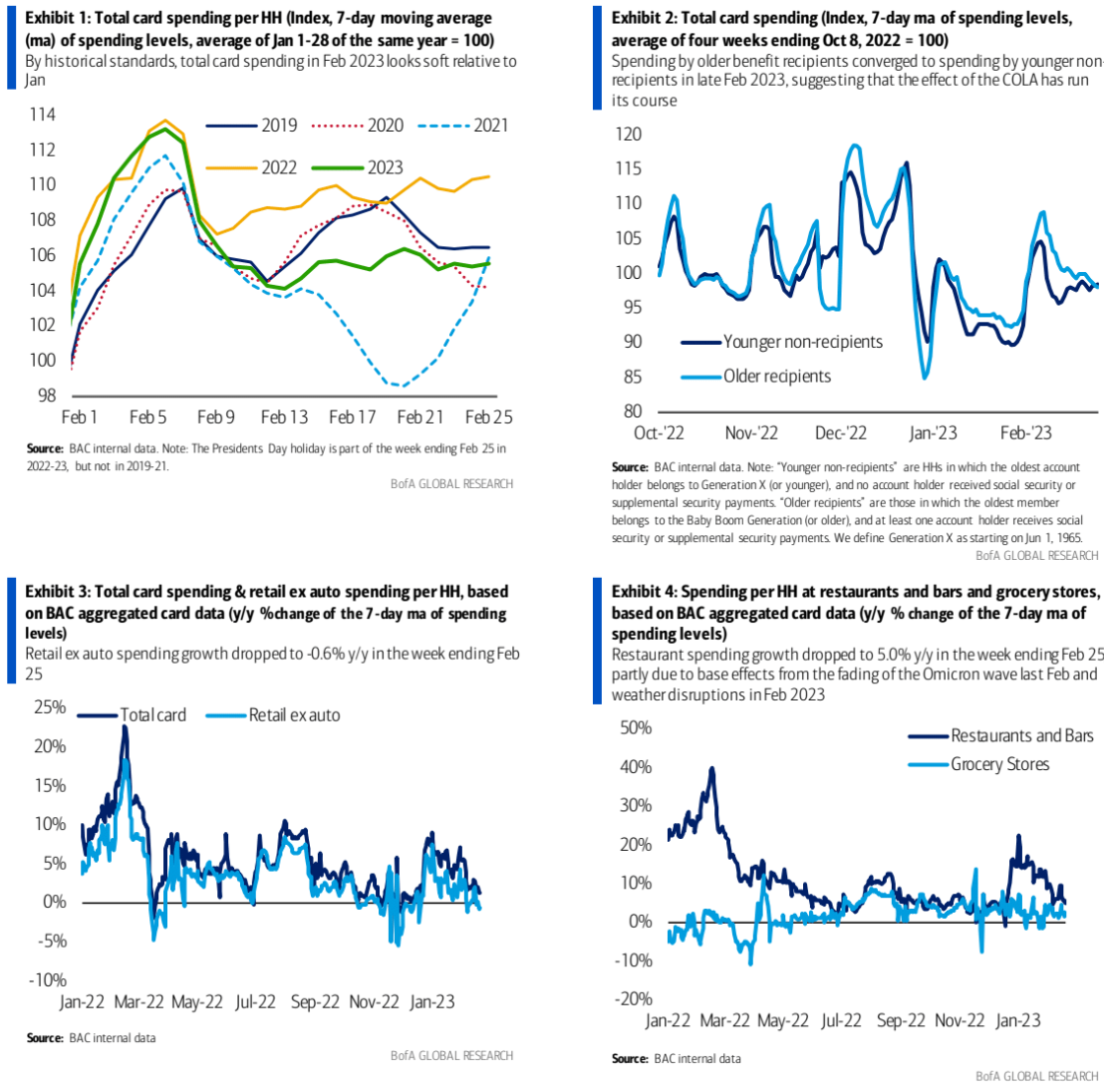

A critical issue in terms of the US economic outlook is how long the acceleration in activity that started in January will continue. Here we use BAC aggregated credit and debit card data through February 25 to attempt to answer this question.

January spending: overshoot or undershoot?

In our discussion of the strong January data, we noted that consumer spending might not have fully adjusted to the spike in disposable income, which was driven by robust job market gains, the 8.7% cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) to social security benefits and a few other factors (see BofA on USA: White-hot January). Consistent with this notion, solid spending growth from January carried over into early Feb. (Exhibit 6 and Exhibit 7). The concern, however, was that there might have been a lot of “one-off” spending in January. Some consumers might have made big-ticket purchases or dined out to “celebrate” the increase in their income. Post-holiday clearance sales and unseasonably warm weather in January would have further incentivized such activity. Indeed, spending on durable goods, clothing, and restaurants & bars was particularly strong in January.

Mid-February slowdown

The latest BAC card spending data suggest that the acceleration in consumer spending might have been more short-lived than we were expecting. Card spending per household (HH) slowed to 1.3% y/y in the week ending Feb 25 (Exhibit 5). Exhibit 1 compares spending in Feb to spending in the first four weeks of January in the same year, from 2019 to 2023. We view this as a proxy for sequential spending growth in Feb. According to this metric, 2023 looks considerably weaker than 2019 and 2022 from mid-Feb onwards.

COLA loses its fizz

Last week’s winter storms across the country probably disrupted spending. But we also find evidence that the boost from the Social Security Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) might have run its course. We have previously argued that the COLA likely drove the outperformance in card spending by older HHs relative to younger HHs from Nov to January (again, see BofA on USA: White-hot January). Here we refine our analysis to focus on older benefit recipients vs. younger non-recipients. We find that the gap between the two groups has closed in recent days (Exhibit 2).

While it is possible that older HHs were disproportionately impacted by the inclement weather, the latest trends in the BAC card data suggest that consumer spending could be returning to its tepid pace from 2H 2022. Continued weather disruptions mean it could take a few more weeks to get a clean read on the data. Stay tuned.

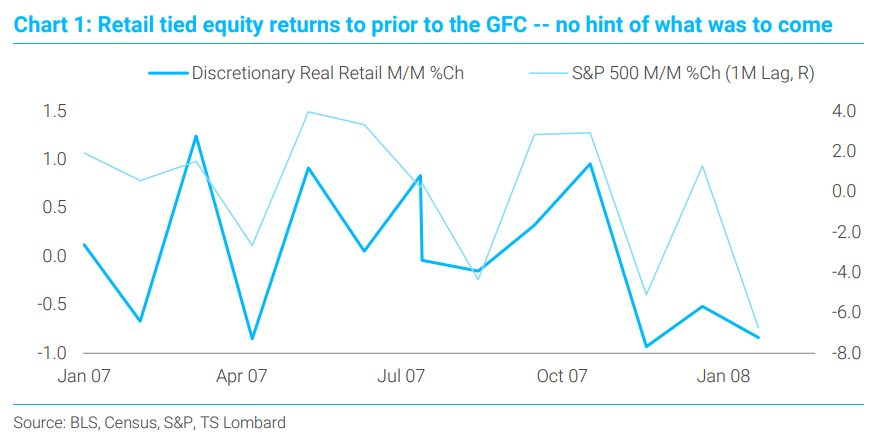

These late-cycle rallies and economic pops are pretty typical:

I still think a recession is unavoidable in the US:

He is also a former gold trader and economic commentator at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, the ABC and Business Spectator. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review.