The intensification of Russia’s war in Ukraine, with its large-scale invasion in February 2022, has up-ended the security order in Europe. The range of actions taken in support of Ukraine has encompassed sanctions, military equipment and training, and broader financial and humanitarian aid; taken both unilaterally by Ukrainian allies, and through international organisations notably, the G7 and NATO.

This explainer looks at the UK and EU responses to the war in Ukraine, setting out the means by which both have been providing assistance to Ukraine, and how Russia’s war in Ukraine has led to a shared foreign policy approach pursued by the EU and the UK.

What sanctions has the UK imposed on Russia?

Following Russian threats of a full-scale invasion, military build up and the decree by President Putin recognising the occupied regions of eastern Ukraine as ‘independent’, the first tranche of sanctions was released on 22 February 2022, freezing the assets of three Russian oligarchs and five banks.

Two days later, on the first day of the invasion, the second tranche was released imposing restrictions on trade, such as a ban on exports of critical electronic components that could be used in communications and aerospace, as well as designation of more Russian oligarchs and entities.

On the same day Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the strategy would evolve into “a rolling programme of intensifying sanctions”, progressively involving broader circles of Duma members, the Russian elite, Russian military leaders responsible for targeting civilians, and their families; subjecting them to travel bans, freeze of non-monetary resources such as properties, alongside trade bans on money market instruments, assets freeze, embargo on products, tariffs, etc.

How does this differ from the EU?

The EU strategy for sanctioning Russia resembles the British one. While the UK implements a “rolling programme of intensifying sanctions”, the EU releases sanctions in ‘packages’ further restricting economic relations. Essentially, this is the same method with a different name.

The way in which the sanctions are implemented also overlaps – each ‘package’ includes broadening criteria for the designation of individuals, embargoes on products and so on. The range of individuals, entities, and products sanctioned by the UK and EU is broadly aligned.

Since the intensification of the war in 2022, the EU has implemented ten such packages. The decision-making process is in many ways similar to the British system: the sanctions are decided by the legislative branch, with a formal review system, and changes implemented as amendments and revocations.

How has Brexit affected UK sanctions policy?

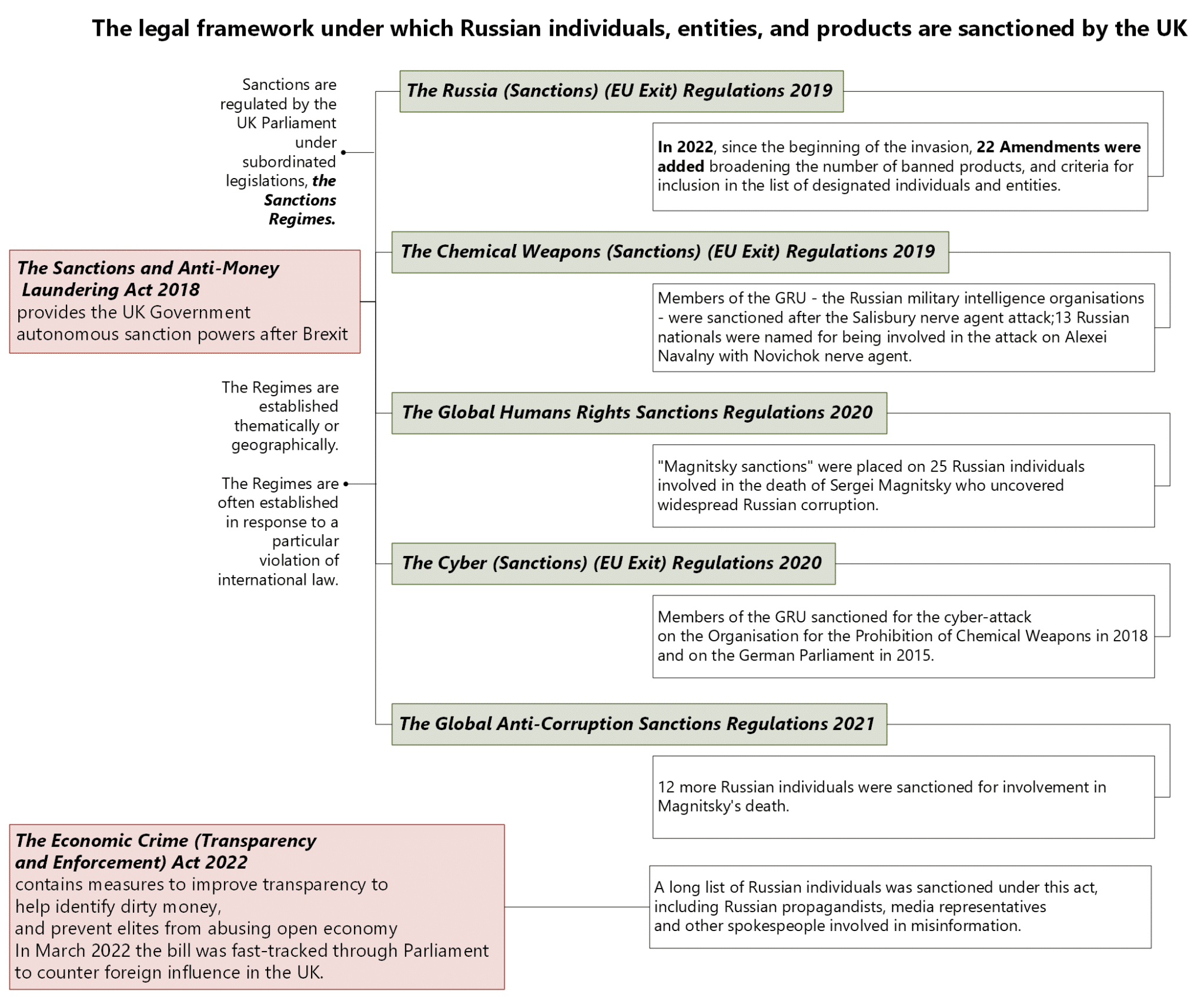

Until Brexit, on 31 January 2020, the UK coordinated with its fellow member states to reach a political agreement by the European Council to apply most sanctions. The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 was passed to provide autonomous powers to the UK government after Brexit and was enforced fully only in December 2020.

Under this act, Parliament can implement sanction ‘Regimes’, which are usually created as a response to a particular violation of international law. The main Regime under which Russian products, entities, and persons are designated is the Russia (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019. This domestic UK legislation negotiated after Brexit aimed to ensure that Britain would continue with the regime originally implemented within the EU to deter and counteract Russian aggression in Ukraine. It was enforced in January 2020, and by the end of 2022, nineteen amendments were added.

Each ‘tranche’ of sanctions includes an Amendment (or a few of them) to the Russia Regulations 2019 further restricting trading relations, and broadening criteria for designations of individuals and entities. The fact that new Regimes are standalone Regulations and have to be changed through amendments was the reason why initially, in the first month of the invasion, the UK was slower in sanctioning Russian individuals compared to the EU in terms of overall numbers.

An additional piece of legislation was fast-tracked through the Parliament on 14 March 2022, the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022, which provided a more efficient framework for designation of individuals. Thanks to this legal adjustment, the UK has designated a higher number of individuals than the EU.

However, as the timelines and the graph on designations illustrate, there is no clear leader between the EU and the UK in the sanctions implementation. The EU designated more entities, but the UK designated more individuals. The EU was first to implement embargoes on a number of key products, but the UK has done far more in terms of sanctions on energy fuels.

Has the UK coordinated its sanctions policy with other states?

In the early days of the war, the G7 became a setting for ad hoc sanctions coordination, where the allies could meet and discuss a common strategy. Other international organisations that had previously served as a platform for sanctions coordination such as the UN and the OSCE became obsolete, with Russia holding decision-making powers.

Over the course of 2022, the G7 has proved itself to be efficient and, on the anniversary of the invasion, its intention was to form an ‘Enforcement Coordination Mechanism’ to improve information sharing, which is crucial for efficiency of sanctions policies.

“The collective sanctions regime has not yet resulted in a shift in Russian policy.”

The G7 is now the main platform for setting objectives. It has also set up the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (REPO) task force, which also includes Australia, as an additional information sharing and collaboration platform. Adding Australia to collaboration aims to broaden geographical scope and increase the allies’ share of global GDP. The G7 discusses issues behind closed doors, and the Joint Communications give a picture of smooth cooperation but in rather vague terms such as ‘wide array of sectoral and individual targets’ or a continuous commitment ‘to impose further severe sanctions.’

Despite the shared political objectives, the timing of sanctions implementation varies in each jurisdiction. There seems to be no clear leader in the enforcement of sanctions policies. However, the UK and EU strategies are more closely aligned than those implemented by the US.

What impact have the sanctions had on Russia?

The collective sanctions regime has not yet resulted in a shift in Russian policy. The economic impacts of sanctions on Russia appear mixed. Research suggests that, on one hand, after a year of extensive sanctions Russia has fallen into recession, but on the other hand economic instability or a full economic collapse are unlikely.

For example, the coordination of sanctions is not as effective in cases when the state is capable of establishing alternative economic connections, and Russia’s trade with China and India has significantly grown in 2022.

It is also anticipated that continuing sanctions over an extended period may have an increasing effectiveness. After the first wave of sanctions, the Russian economy received some indirect benefits insofar as there were higher revenues from a rise in the price of energy, expansion of local tourism, rise in domestic production and de-dollarisation process. However, the longer sanctions are in place, the bigger the deficit in the Russian federal budget, and these initial positive gains will likely not be able to compensate in the long term.

What military support has the UK provided?

The UK has consistently supported Ukraine with military means since before the 2022 invasion. Defence and security cooperation through bilateral agreements can be dated back to 2001, and the current relationship was reinforced by signing the multi-layered Political, Free Trade and Strategic Partnership Agreement in November 2020.

Since the Crimea Crisis in 2014, the British government has been providing lethal and non-lethal aid, investment schemes, and training programmes, mostly on a bilateral basis but partially to deliver on NATO commitments. The provision of equipment was coordinated specifically with the NATO-Ukraine Commission and through initiatives such as the US/Canada/UK/Ukraine Joint Commission for Defence Reform and Security Cooperation established in July 2014.

The most notable initiative between 2014 and 2022 was Operation Orbital – a mission set up and led by the UK which aimed to train Ukrainian troops up to NATO standards. More than 22,000 members of the Armed Forces of Ukraine were trained over the course of the programme.

Op Orbital was followed up by Operation Interflex, which was established in June 2022 and began a month later. In 2022, the UK trained 15,000 Ukrainian soldiers and aims to train another 30,000 in 2023. In February 2023, the UK also led cyber warfare exercises in live-fire cyber battle with 11 other countries (including Ukraine), organised by specialists from Defence Cyber Marvel.

Aside from providing training, after the 2022 invasion the UK was the first to send lethal weapons to Ukraine. Throughout the year, the UK provided a range of equipment ranging from tanks, ammunition and guns to defence systems, as well as non-lethal aid, such as armour, helmets, emergency vehicles, medical aid, and more.

“The military support provided by the UK and the EU has been broadly similar in scope, but there are some points of difference over the pace of delivery.”

More recently, there was a discussion in Parliament on whether the UK should also provide fighter jets, but it has not been decided at this stage. However, Prime Minister Sunak has promised to commence a training programme for Ukrainian pilots, and the UK delivered the long-range air-launched cruise missiles Storm Shadow.

The UK also made a substantial related investment in the defence industry: in May 2022, £25m was provided in support of Ukraine’s Armed Forces to harness niche UK-based technologies to bolster Ukrainian artillery, coastal defence and aerial systems.

What military support has the EU provided?

Between February 2022 and March 2023, the UK has committed £4.6 billion in military assistance. On a per capita basis, this is significantly more than EU member states.

An enlargeable version of the timeline of UK spending on arming Ukraine can be found here.

Between February 2022 and May 2023, the EU committed around €13 billion on military equipment and training including around €5.6 billion under the European Peace Facility (an off-budget EU instrument), and the rest by the member states directly. The EU Military Assistance Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM Ukraine) is the main framework for training and provision of lethal and non-lethal aid to the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

The impact of Russia’s February 2022 invasion has been a trigger for a major transformation in the EU’s capacity to respond to crises. Individual member states, notably Finland and Sweden’s applications for NATO membership and Germany with its Zeitenwende, have gone through a rapid reflection on their security posture, and there have been commitments by most European states to raise the level of their defence expenditure.

The military support provided by the UK and the EU has been broadly similar in scope, but there are some points of difference over the pace of delivery. For example, Germany initially prevented Finland and Poland from supplying Leopard 2 tanks (which it held the licenses for) to Ukraine, which was a significant event highlighting the interdependencies between EU states which can slow down the provision of military equipment and training.

In contrast, the UK’s decision to supply Challenger 2 tanks to Ukraine was politically uncontroversial in Britain. The vanguard of European states seeking to act at greater pace and scale in weapons deliveries to Ukraine has encompassed some EU and non-EU states, as illustrated in the country signatories of the Tallin Pledge.

What other assistance has been provided?

EU assistance to Ukraine is significantly more focused on financial, economic, and humanitarian aid. Since the start of Russia’s war in 2022, the member states and the financial institutions have committed €37.8 billion in ‘macro-financial assistance and budget support’, which includes pledges from an international fundraising campaign, compared to the €13 billion committed to military equipment and training. The €37.8 billion is spent between humanitarian assistance, loans, budgets, and other types of support. The EU provides emergency logistical hubs to deliver shelters, decontaminants, power generators, and medical provisions for urgent treatments of Ukrainian patients. There are also solidarity lines – corridors allowing for agricultural goods and infrastructure developments to support them.

“The case for increased spending on defence will be need to made against a backdrop of intensive competition for other priorities for public expenditure”

In 2022, the UK committed approximately £1.9 billion in economic and humanitarian support, compared to £4.6 billion in military aid. Out of the £1.9 billion, £220 million was spent on humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, making the UK a leading bilateral humanitarian donor. The money is mostly spent on the provision of life-saving supplies, such as medical and food aid, as well as power generators, warm winter clothing and insulating shelters to help with harsh winter conditions. Other elements include budget support for public sector salaries and government services and support for the Ukrainian economy including the energy sector.

Is the level or type of support likely to change over time?

For both the UK and the EU, Russia’s war has instigated a debate on the responses to the new circumstances of European security. The EU member states have had to adjust to the new reality and the EU had experienced some form of a paradigmatic shift – where collective security and defence strategy has become at least equally important to economic and political union – providing military equipment to a third country for the first time. Closer political and economic relations look set to be a key element of EU support for Ukraine in future years. For example, the EU has already shown flexibility over its own notoriously stringent accession criteria for membership by, in June 2022, granting Ukraine, along with Moldova, candidate status as potential future member states. A key challenge will be whether substantive progress can be made on the progress of the candidacy in the coming years.

For the UK there is the key challenge of delivering on the commitments to increase defence spending that have been made in response to Russia’s actions. Voices have already been raised on the impacts of supplying weapons to Ukraine having the effect of depleting the UK’s own military capabilities and also demonstrating the need for increased funding and modernisation of the British Army. More broadly the case for increased spending on defence will be need to made against a backdrop of intensive competition for other priorities for public expenditure, notably health and mitigating the cost of living crisis.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has also provided the basis for a rapprochement in combined EU and UK foreign and security policy in support of a shared objective. As Russia will present a major diplomatic and security challenge for the foreseeable future, the EU and the UK will find it necessary to continue to coordinate their respective measures of support for Ukraine.

By Professor Richard Whitman, UK in a Changing Europe, and Kamila Kwapińska, Research Assistant, University of Kent.