The U.S. economy remained resilient early this year, with a strong job market fueling robust consumer spending. The trouble is that inflation was resilient, too.

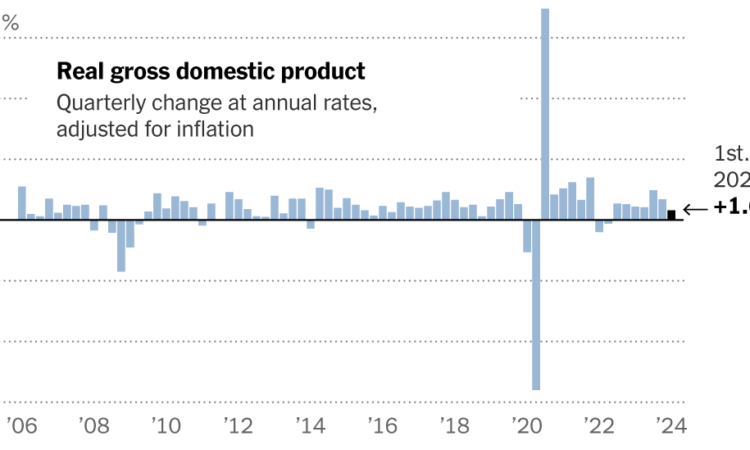

Gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation, increased at a 1.6 percent annual rate in the first three months of the year, the Commerce Department said on Thursday. That was down sharply from the 3.4 percent growth rate at the end of 2023 and fell well short of forecasters’ expectations.

Economists were largely unconcerned by the slowdown, which stemmed mostly from big shifts in business inventories and international trade, components that often swing wildly from one quarter to the next. Measures of underlying demand were significantly stronger, offering no hint of the recession that forecasters spent much of last year warning was on the way.

“It would suggest some moderation in growth but still a solid economy,” said Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Bank of America. He said the report contained “few signs of weakness overall.”

But the solid growth figures were accompanied by an unexpectedly rapid acceleration in inflation. Consumer prices rose at a 3.4 percent annual rate in the first quarter, up from 1.8 percent in the final quarter of last year. Excluding the volatile food and energy categories, prices rose at a 3.7 percent annual rate.

Taken together, the first-quarter data was the latest evidence that the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame inflation have stalled — and that the celebration in financial markets over an apparent “soft landing” or gentle slowdown for the economy had been premature.

“It increases the chances of a harder landing,” said Constance L. Hunter, an economist at MacroPolicy Perspectives, a forecasting firm. “The inflation data was the surprise.”

At a minimum, stubborn inflation is likely to mean that the Fed will wait at least until fall to begin cutting interest rates. Some forecasters think it is possible that policymakers won’t just keep rates “higher for longer,” as investors have been anticipating for several weeks now, but might actually raise them further.

“It is a huge shift because all of a sudden ‘higher for longer’ could mean another hike,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at KPMG. For now, she said, the Fed is stuck in “monetary policy purgatory.”

Financial markets fell on the news. The S&P 500 index ended the day down about half a percentage point, and yields on government bonds rose as investors anticipated that borrowing costs will remain high.

Investors aren’t the only ones who could suffer if interest rates remain high. There are mounting signs that high borrowing costs are weighing on Americans’ financial well-being. Consumers saved just 3.6 percent of their after-tax income in the first quarter, down from 4 percent at the end of last year and more than 5 percent before the pandemic.

The signs of strain are particularly acute for lower-income households. They have increasingly turned to credit cards to afford their spending, and with interest rates high, more of them are falling behind on their payments.

“There is a sense that lower-end households are increasingly stretched right now,” said Andrew Husby, senior U.S. economist at BNP Paribas.

Yet despite those strains, consumer spending, in the aggregate, shows little sign of cooling down. Spending rose at a 2.5 percent annual rate in the first quarter, only modestly slower than in late 2023, and spending on services like travel and entertainment actually accelerated.

Spending has been driven particularly by wealthier consumers, whose low debt and fixed-rate mortgages have insulated them from the effects of higher interest rates, and who have benefited from a stock market that was until recently setting records.

“Higher income households feel very flush,” said Brian Rose, senior economist at UBS. “They’ve seen such a huge run-up in the value of their house and the value of their portfolios that they feel like they can keep spending.”

That presents a conundrum for the policymakers at the Fed: Their main tool for fighting inflation, high rates, is doing little to tamp down spending by the wealthy while hurting poorer households. And yet if they cut those rates, inflation could accelerate again.

Even so, forecasters said the overall economic picture remains surprisingly rosy, especially when compared with the glum predictions of a year ago. Unemployment has remained low, job growth has stayed strong and wages have continued to rise, all of which helped after-tax income to outpace inflation in the first quarter.

Businesses stepped up their investment in equipment and software in the first quarter, a vote of confidence in the economy. The housing market also rebounded, although that was due partly to a dip in mortgage rates that has since reversed.

Even one of the drags on growth in the first quarter — a swelling trade deficit — mostly reflected demand from the United States. Imports rose as Americans bought more goods from overseas, while exports rose more modestly.