When people hear the term “American exceptionalism,” they tend to think of a jingoistic expression dished out by crass pundits who see the United States’ culture, morals, or broader position in the world as superior to other nations. But ever since the end of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), this divisive term has slowly taken on a new meaning in financial circles.

For economists, analysts, investors, and the like, American exceptionalism refers to the relative outperformance of the U.S. economy and stock market compared to its developed peers in recent decades, particularly in the wake of the pandemic. It’s the idea that there’s a confluence of factors—a special sauce, if you will—that has made the American economy and markets structurally more robust and resilient in the 21st century.

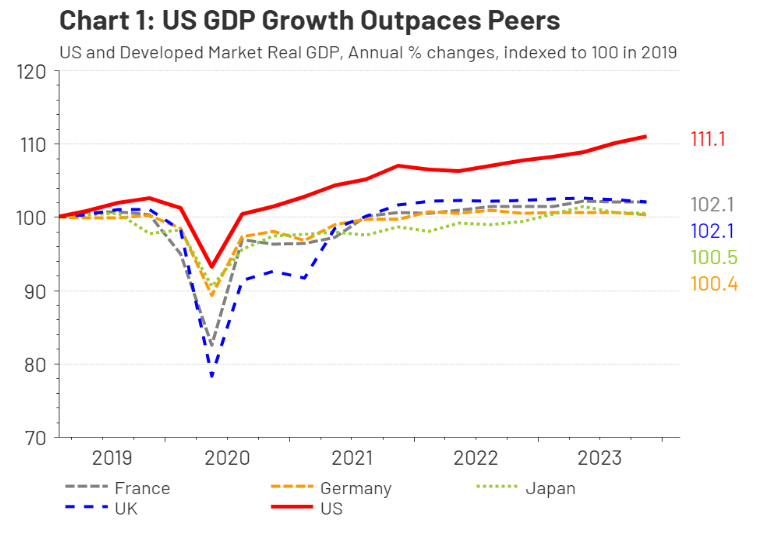

There’s certainly some evidence to back up this thesis. U.S. GDP per capita has surged compared to its developed peers’ over the past decade.

In fact, while the U.S. and eurozone had roughly the same overall GDP in 2008, the U.S. economy is now about double the eurozone’s.

And a decade ago, the Chinese economy’s rise to overtake America’s as the world’s largest was seen as inevitable. But amid a real estate crisis that’s battered China’s middle class, soaring youth unemployment, a crackdown on businesses, an expanding trade war with the U.S., and the end of debt-driven growth, that trajectory is now in question. Warnings of a “lost decade” have gotten louder, especially as President Xi Jinping adopts more ideological policies that weigh on growth.

In financial markets, U.S. outperformance is apparent too. Since the beginning of 2009, U.S. stocks have trounced the competition, with the S&P 500 soaring more than 500%, while Japan’s Nikkei 225 jumped 336%, and Europe’s STOXX EURO 600 rose just 130%.

The list of reasons behind this run of American outperformance is long and varied. Experts point to several long-term strengths, like the U.S.’ labor market flexibility and robust capital markets, as well as more recent or short-lived dynamics, including growing energy independence and an aggressive monetary and fiscal response to COVID-19.

“I’m very much a believer that American exceptionalism isn’t a temporary phenomenon, but will continue for the rest of the decade and maybe beyond,” Ed Yardeni, the veteran Wall Street strategist and economist who runs Yardeni research, told Fortune.

In fact, since the beginning of the decade, he’s been predicting a “Roaring 2020s scenario” that features a productivity and AI-induced U.S. economic boom. While some deride claims of American exceptionalism, Yardeni—and a number of other veteran investors like him—are willing to put money on it.

“I’ve been recommending overweighting the U.S. for a long time in a global portfolio, since 2010,” Yardeni said. “I think that that’s worked really well and should continue to work.”

Of course, there’s always a counterpoint worth mentioning. MUFG’s head of U.S. macro strategy George Goncalves questioned whether the U.S. economy and markets are truly exceptional, or whether they’re only the “cleanest shirt” in a dirty closet of struggling developed economies. He also noted that the U.S. economy continues to be full of haves and have-nots amid sky-high income and wealth inequality.

“American exceptionalism creates this perception that everyone’s benefited,” he said. “And I don’t think that’s true.”

Finally, Goncalves wondered if the U.S.’ recent run of outperformance compared to its developed peers can continue, given that so much of it has been driven by record fiscal spending, and the national debt is now over $34.7 trillion.

“Is that sustainable? Interest costs matter and consumers have run out of excess savings,” he told Fortune. “It’s almost like a sugar high has created this perception of American exceptionalism when the reality is it was mostly just a big spending spree.”

Still, others point to several key advantages, both long- and short-term.

U.S. ‘special sauce’: Long-term keys to American exceptionalism

Chris Konstantinos, chief investment strategist of RiverFront Investment Group, a Richmond-based investment management firm, is an American exceptionalism believer who has been dissecting the factors behind the phenomena for quite a while. In an interview with Fortune, he explained that several years ago his team was looking at profit margins in the industrial sector around the world when they noticed that U.S. businesses tended to be “structurally” more profitable. “It begged the question of ‘why?,’” Konstantinos said.

After parsing through lots of data and speaking with experts, the veteran strategist discovered numerous reasons for the American economy’s unique strength, including flexible labor markets, robust capital markets, a culture for nurturing tech and innovation, vast natural resources, younger demographics than developed peers, the dollar’s status as the dominant reserve currency, and many more. But there were a few key long-term advantages that he singled out as being the most important because of their ability to drive productivity growth.

“Many countries have these various advantages, but none have the combination—or the entire package—quite like the U.S. does,” Konstantinos said. “I think of it as America’s ‘special sauce.’”

Labor market flexibility

First, the U.S. labor market is “less encumbered by regulation” than developed peers, enabling companies to more readily increase or lower the size of the workforce to meet changing industry conditions.

That might not always be great for workers, but it is good for the economy, according to Konstantinos. Flexible labor markets help U.S. corporations protect profits, increase productivity, and more readily respond to unexpected events like a pandemic or economic crash.

Demographics

Second, although headlines about America’s aging population are now common, the reality is that compared to other developed peers, the U.S. is doing well demographically. The median age of U.S. citizens is 38.5 years old, compared to 46.7 in Germany, 48.1 in Italy, and 40.7 in the U.K., and 49.5 in Japan. The U.S. also has higher immigration rates from countries with lower median ages on average.

“It’s true that regions like India, Brazil and Africa have much younger demographics, but compared to most of our current economic peers, we are doing pretty well,” Konstantinos said, noting that “a young, relatively upwardly mobile society tends to produce strong consumption, which helps fuel our economy.”

A culture of innovation and robust capital markets

Third, as JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said in 2016, Americans have “innovation from the core of our bones,” and are willing to take on risks to start new businesses, enter new industries, and invest in themselves.

While many have questioned whether the American Dream is still alive, immigrants worldwide also continue to flock to the U.S. for a better life and can have immense success when they get here. Look no further than the Taiwanese-American Nvidia co-founder Jensen Huang, or the South African-American Tesla CEO Elon Musk for evidence of this reality.

Ignoring the slightly nationalistic rhetoric of Dimon, there are some structural factors that facilitate U.S. innovation, including the ease of starting new businesses in the U.S. compared to other developed nations; the quality of U.S. intellectual property protection; as well as significant government spending on research and development that benefits private enterprises.

The U.S. is often considered a better place to do business when taking into account the more onerous regulations in Europe. In fact, it’s the sixth most business-friendly nation worldwide, according to the World Bank, while the U.K. is eighth on that list, Germany is 22nd, Canada is 23rd, Japan is 30th, and France is 33rd. A lack of patent protection in China has also led many companies to fear entering the country. China steals between $225 billion and $500 billion worth of IP annually, according to estimates from the cyber intelligence company CyFirma.

With big tech companies’ profits soaring, the U.S. is only increasing its research and development spending overall as well. “And that’s paying off in more innovations and so on,” according to Yardeni.

“I think another point you might want to make is that the U.S. has the most developed and sophisticated capital markets in the world,” Yardeni added. “So the U.S. has the ability to provide a great deal of financing for all sorts of innovation and startups.”

The veteran investor noted that the U.S.’s giant investment banks, venture capital firms, and private credit lenders all boost innovation by providing equity and debt financing for new businesses, business expansions, and more.

The productivity edge

The factors listed above are critical to American exceptionalism in various ways, but Konstantinos said their main benefit could be their contribution to the U.S.’ productivity advantage and higher rate of corporate earnings growth.

To his point, U.S. productivity, as measured by real GDP per hour worked, has surged compared to its developed peers for decades now, and that’s only accelerated since the pandemic.

RiverFront Investment Group

Short and medium-term drivers of American exceptionalism post-pandemic

Beyond the long-running trends in American business and culture that may help create a form of American exceptionalism, there are numerous factors that have helped the U.S. economy outperform in just the past few years.

Fiscal, monetary stimulus—enabled by dollar dominance

Record fiscal spending and loose monetary policy were key drivers of U.S. outperformance during and after the COVID era. While developed nations worldwide implemented spending programs meant to prevent job losses and boost the economy, the U.S. federal government was by far the most aggressive, dishing out $4.6 trillion, or roughly 10% of U.S. GDP in both 2020 and 2021, through six COVID-19 relief packages.

After the big spending packages of the COVID era, a string of legislation from President Joe Biden—including the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act, and even parts of the Inflation Reduction Act—also helped to kickstart the U.S. economy.

Jay Hatfield, CEO of Infrastructure Capital Advisors, explained that this spending drove investment into manufacturing and construction at a critical weak point for the U.S. when the Fed was rapidly raising interest rates, helping to prevent a recession.

Although Hatfield criticized some of the fiscal policies of the pandemic era, labeling them a form of “helicopter money” that only served to exacerbate inflation, he argued that Biden’s “infrastructure spending that offset construction weakness…was the appropriate counter cyclical investment.”

Konstantinos noted that the benefits of this extreme level of fiscal spending are only available to the U.S. because of the dominant position of the dollar. By contrast, a country that borrows heavily in another country’s currency risks sparking a crisis in its own currency if debts look less sustainable.

“You can see this in the availability and relatively low cost of capital in the U.S. relative to other areas, even with the U.S.’ high government debt burden,” he said.

Energy independence

The U.S. is also far less reliant on energy imports than other developed nations. That wasn’t always true, but both U.S. natural gas and oil production hit record highs in 2023. The United States now produces more oil than any country in history, an average of nearly 13 million barrels per day in 2023, up from just 4.5 million in 2009.

This relative energy independence helped to insulate Americans against at least some of the pain that came when oil and natural gas prices spiked after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, while Europe wasn’t so lucky. Natural gas prices in Europe, which was highly reliant on Russian imports, peaked at over over $70 per million British Thermal Units (BTU) in August 2022 after the Ukraine war began, compared to a peak of just $10 per million BTU in the U.S.

Reduced impact of rising rates

Rising interest rates have held back developed economies worldwide over the past few years, but U.S. consumers and businesses were more prepared than most.

As BlackRock’s global CIO of fixed income, Rick Rieder, explained in a late April interview with Fortune, many large U.S. corporations and wealthy retiring boomers have effectively become net lenders, rather than borrowers over the past few years due to low debt and high cash levels. With rates rising, that’s led to a significant economy- and inflation-boosting income stream for some key businesses and consumers, rather than the typical spending slowdown caused by rising borrowing costs.

Something similar happened in the mortgage market as well. Many Americans were able to lock in low interest rates during the pandemic, insulating themselves from rising borrowing costs over the past few years. This was only possible because, unlike many other developed nations, the most common mortgage in the U.S. is a 30-year fixed rate mortgage.

In the U.S., 79% of all mortgages had fixed rates of 30 or 15 years in 2023, according to Bankrate. However, in the U.K., for example, 74% of mortgages currently have interest rates that are fixed for just two to five years before they need to be refinanced, according to data from the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority.

As a result, while a majority of U.K. mortgage holders have now had to refinance at higher rates, nearly 90% of U.S. homeowners still have mortgage rates under 6%, even as average 30-year mortgage rates spiked to 8% last year before falling to nearly 7% today, Redfin data shows.

With all this in mind, even Fed officials are beginning to consider “the possibility that high interest rates may be having smaller effects than in the past,” the minutes of the May 1 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting revealed.

The wealth effect from baby boomers

American baby boomers are collectively worth over $78 trillion, making them the wealthiest generation of retirees in history. For reference, total European wealth—across the entire continent for every generation—was $104 trillion in 2022, according to UBS’ Global Wealth Report 2023.

This immense wealth has helped the U.S. economy thrive over the past few years by supporting consumer spending, which makes up roughly 70% of GDP.

“The baby boomers have had a very important impact on the economy. They’re retiring and that’s one of the reasons that consumer spending has held up, because they’re spending their retirement assets,” Yardeni explained. “I think that’s been an important source of strength.”

More AI-linked stocks, tech-focused universities amid the AI boom

Tech dominance has also been key to the success of U.S. stocks in recent years. That’s largely because the AI boom has mostly benefited tech stocks, particularly big tech stocks, and eight out of 10 of the world’s largest tech companies being U.S.-based. The semiconductor giant Nvidia alone has accounted for roughly 34% of the rise in the S&P 500 this year.

“There’s no other country that has anything like the Magnificent Seven,” Yardeni noted. “And these technology companies are extraordinarily successful, generating lots of profits and cash, so that they can continue to spend money on research and development.”

The U.S. certainly has more tech companies that can take advantage of the AI boom than its developed peers, and one key strength that makes this possible is the U.S. university system and its research and development.

“Tech and universities are another big factor—and those go together,” Infrastructure Capital’s Hatfield said. “It’s not an accident that the tech industry is in the Bay Area, it’s because Stanford, and to a lesser degree, Berkeley, are there.”

An era of corporate tax competitiveness

Former President Donald Trump’s corporate tax cuts are another major factor that has helped the U.S. outperform its developed peers in recent years, according to Infrastructure Capital’s Hatfield. Trump cut the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21% in 2017, putting the U.S. more in line with developed peers.

“We now have a competitive corporate tax rate, where we didn’t prior to 2017,” Hatfield said, arguing that this has made U.S. corporations more resilient, more likely to invest in growth or R&D, and helped prevent key U.S. companies from domiciling in more tax-friendly regions, thereby improving economic growth.

To be sure, not all that money went to innovation and investment. Trump’s tax cuts also spurred a stock buyback surge. In just the first 45 days after Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act became effective, there was a record $145 billion in stock buybacks by U.S. companies, according to data from Birinyi Associates, per CNBC.

Still, Hatfield argued that the corporate tax cuts have been the most important factor in the U.S.’s recent string of economic exceptionalism. “Partly because people don’t appreciate it, and politicians want to be in denial about it….but it’s critical to global competitiveness,” he said.

A word of caution

When it comes to what American exceptionalism means for investors, experts are mostly optimistic.

The bulls—Konstantinos, Yardeni, and Hatfield—all believe American exceptionalism is here to stay, and that investors should keep that in mind moving forward. Yardeni said that he’s expecting U.S. stocks to continue their “melt-up” this year and beyond as AI boosts productivity, inflation fades, and the Fed (eventually) cuts rates.

Infrastructure Capital’s Hatfield noted that he’s been bullish for years now, even when others were predicting a U.S. recession, due to many of the structural advantages the U.S. economy has over its peers. The Wall Street veteran currently has a 6,000 price target for the S&P 500 this year, and he said one of the main reasons why is quite simple: “the AI boom is broader than people thought.”

Riverfront’s Konstantinos also said he currently favors the U.S. over international markets, and has for some time, even if international valuations are often more appealing. “American ‘economic exceptionalism’ does mean higher and more stable cash flows from U.S. public companies in our view, which we believe has led to superior returns,” he argued.

However, over the longer-term, Konstantinos argued that a “reflationary global economic backdrop” could benefit the earnings of some of the more cyclically-oriented businesses in developed markets abroad. “Stay tuned,” he said.

And, as a reminder, MUFG’s Goncalves warns that what may seem like American exceptionalism on the surface, could actually be just a matter of chance. “I look at it like this was the way the stars aligned. You had a lot of savings, and you had a lot of money thrown into the system, all these these fiscal measures, and then that can be conflated as ‘Oh, it’s exceptionalism. But in reality, it’s just a lot of spending,’” he said.