In my two-part analysis of how to end the U.S. government’s endless budget deficits, I presented a reform model that would replace the current economically redistributive welfare state with a three-layered welfare system. The point of the reform model is to combine the most efficient functions of government and the private sector, while containing government costs and maximizing the freedom of individuals and families to tailor their financial security to their needs and preferences.

This model is revolutionary in the sense that it ends the welfare state that was built under President Lyndon Johnson and replaces it with a socially conservative model. Its radical departure from the welfare state that has prevailed for over half a century is driven in large part by the fact that the U.S. government is chronically unable to fund this welfare state.

An often-heard point of criticism against my reform model is that it would be a lot easier to raise taxes and preserve, even expand, the American welfare state. This view, which has a standard bearer in Bernie Sanders, a socialist U.S. Senator from Vermont, is based on the idea that America would be better off under a fully implemented Nordic welfare state.

Disregarding the ideological side of this idea, there is a pressing fiscal problem: the Nordic welfare states are also struggling with budget deficits—despite (or, as an astute macroeconomist would point out, because of) having much higher taxes than America has today.

Generally, Europe is having problems paying for its government. In the first three quarters of 2023—Eurostat has still not released fourth-quarter data—two out of three EU member states ran a budget deficit. Eleven of them had a deficit for the third quarter in a row, and 20 of the 27 member states had a deficit in at least two of the first three quarters of 2023.

This is not a new problem for Europe. As I explained back in March, the European economy is standing still and is in a state of long-term stagnation thanks to big governments that require high taxes. The combination of growth-crippling large government spending programs, a regulatory apparatus that comes with said spending, and high and widespread fees and taxes is detrimental to Europe’s economic future.

At the core of the problem is a philosophical approach to government’s role in the economy that Europe shares with America. On both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, government spends the majority—in many cases the vast majority—of its resources on economic redistribution. This means taxing the ‘rich’ at disproportionately high rates in order to give social benefits to the ‘poor’.

As I explained in my two-part article about how to end America’s deficits, the benefits that our welfare states pay out are only to a limited extent designated for those who really are poor. (And I am not even going to discuss the statistical definition of poverty itself.) It is consistent with the current philosophical approach that benefits reach beyond the most vulnerable in our society: if government’s primary goal is to redistribute income, consumption, and wealth, then it is not too concerned with specifically helping the poorest among us.

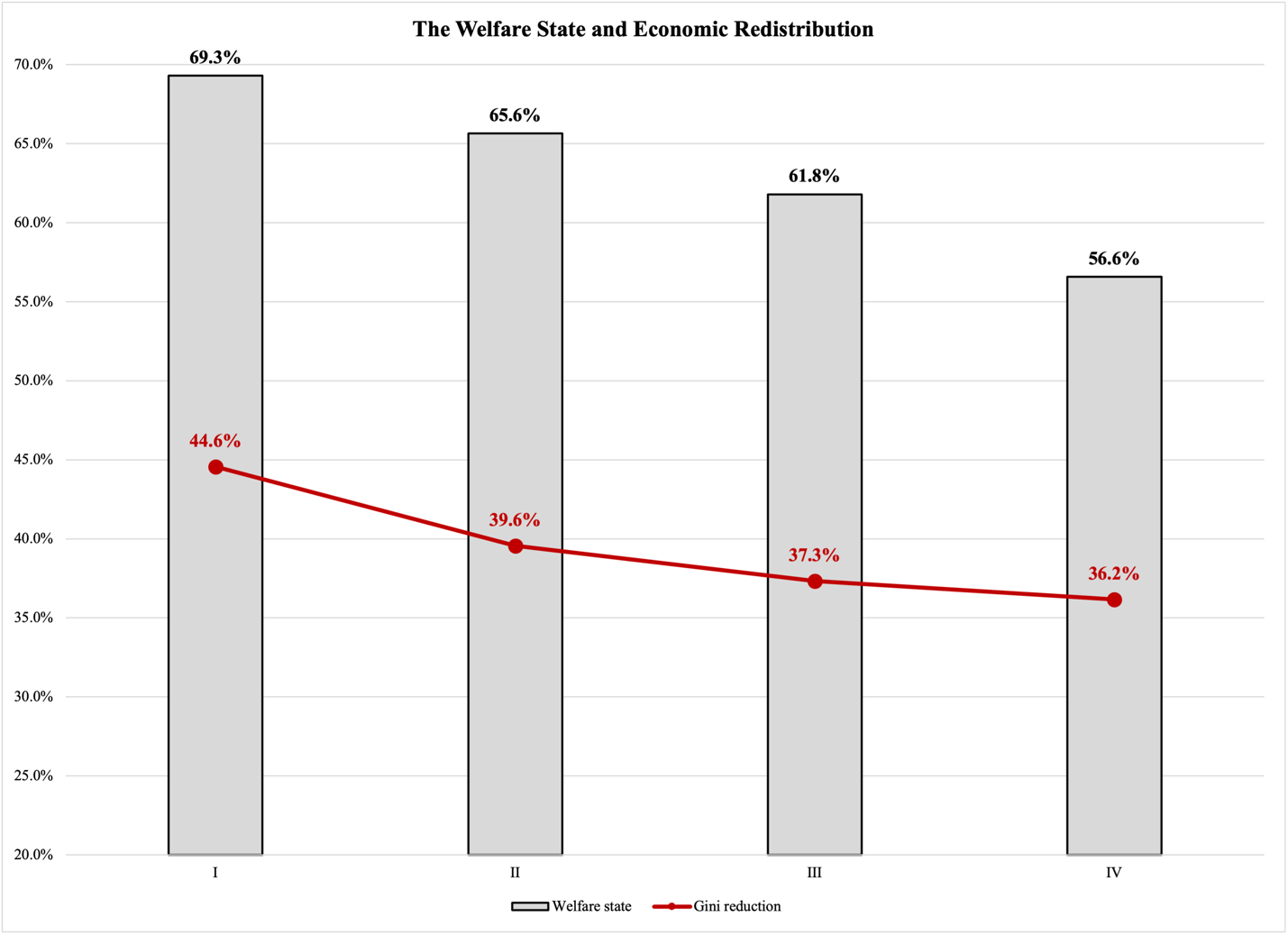

There is no doubt that Europe’s welfare states are designed for the purposes of economic redistribution. We can see this purpose at work in the statistics over economic redistribution: as shown in Figure 1 below, the more of a government’s money that is spent on taking from Pete the Rich and giving to Paul the Poor, the more government alters the market-based distribution of income in the economy.

This may seem trivial, but it is not. There are many government programs that are designed to achieve a certain goal but fail to do so. As Figure 1 shows, the welfare state programs do not fail. It reports observations of the welfare-state share of government spending (gray columns) and the reduction in income differences, measured by the Gini coefficient (red line), for all 27 EU member states from 2010 to 2021. (A high Gini coefficient means big income differences; a low coefficient means small differences.) For each country, each year, we have a pair of observations of these two variables; in Sweden in 2010, e.g., the welfare state consumed 67.3% of all government spending, while the Gini coefficient was reduced by 54.5%.

This means that by using two out of three kronas that the Swedish government had at its disposal, it was able to significantly reduce the income differences—in other words reduce the Gini coefficient—between Swedish households. The Gini coefficient fell by just over half.

We add up these pairs of observations from the 27 EU member states in the years 2010-2021 and get 324 pairs of observations. These are then divided into four groups, with 81 in each. In the first group, the welfare state on average consumed 69.3% of government spending; this money reduces the Gini coefficient by 44.3% on average:

Figure 1

The smaller the welfare state becomes as a share of total government outlays, the less of an impact does government have on income distribution. That does not mean those governments fail on the redistributive front; it is simply a matter of political leaders in those countries not prioritizing economic redistribution as a policy goal.

There are two interesting, contrasting examples: Sweden and Hungary. The Swedish welfare state, which for the period observed here on average accounted for 68% of government spending, reduced the country’s income differences by 53%. The latter number means that the Gini coefficient fell from 56.9 to 26.8, thanks to government policies.

In Hungary, by contrast, the Gini coefficient was reduced from 50.1 to 27.7, a reduction by less than 45%—and the trend over time is toward a gradually smaller reduction. Only 52.7% of the Hungarian government’s spending was designated for economic redistribution. Again, this is deliberate: with a focus on families—not their incomes—the Fidesz-led government has transformed the Hungarian welfare state from a democratic-socialist machine to a socially conservative institution.

Larger welfare states tend to have higher taxes than smaller welfare states. Since higher taxes depress economic growth more than lower taxes do, it is essential for Europe’s economic future that its governments reform their welfare states. They need not look farther than Hungary to find a good example; those who want to go even bolder can look at the model I just proposed for reforming the American welfare state.