While pessimists pundit that the U.S. economy is in trouble, I will maintain the conclusion I reached in Part I: the U.S. economy is strong and shows no real signs of weakness.

Last week’s article was based on labor-market data. Today, we examine the new numbers on GDP growth that the Bureau of Economic Analysis, BEA, released last week. Those numbers confirm that the U.S. economy is ho-humming along: while the actual growth rates are far from spectacular, they are well in line with what we have gotten used to in the past 20 years.

Rather than showing signs of a recession, the numbers from the BEA suggest that the economy took a brief break earlier this year, and it is now back on its long-term growth path. I predicted just that back in December last year: a light, brief slowdown in economic activity, but no recession.

Before we dig into the numbers, I need to acknowledge that the debate over the economy here in the United States has become increasingly politicized in recent years. This is unfortunate, and all practitioners of economics should contribute toward de-politicizing the issue. That is not to say we cannot debate our analyses of the economy—of course we should. But let us separate that debate from whatever political preferences we have.

At the end of the day, facts are facts.

With that said, I am the first to acknowledge that the American economy is nowhere near in perfect shape. We face major problems, but they are for the most part structural in nature. One exception is inflation, which is a transient but irritating problem. It is currently higher than merited by current monetary policy and level of overall economic activity.

GDP growth: strong but not spectacular

Measured from the third quarter last year to the third quarter this year, U.S. gross domestic product increased by 2.67%. The press likes to cite the quarter-to-quarter number, which is also the number that the BEA put on top of its press release. Since this number was almost 5% for the third quarter, it makes for a spectacular news story (at least as far as economic news is concerned).

It is important to establish what this number really tells us: practically nothing. It is especially silent on where the economy is heading; anyone using this number will be led to believe that the economy is falling into a recession every spring. The reason is that first-quarter GDP numbers are always lower than the numbers for the fourth quarter of the preceding year. This is just how the yearly economic cycle works.

Another problem with using the BEA’s lead number is that it is annualized. They take the sum total of the past four quarters of economic activity in one quarter—this time Q3 of 2023—and compare it to the same four-quarter sum a quarter earlier. In other words, all we get is a comparison between two values of a statistical moving average.

If we want to know what is actually happening in the economy, we have to turn to the less used Table 8.1.6 in Section 8 of the National Income and Product Accounts over at the BEA website. This table only adjusts GDP numbers for inflation; everything else is, so to speak, a raw quarterly picture of the American economy.

As mentioned, we find here that GDP expanded by 2.67% in the third quarter. This is the strongest growth rate in any quarter since the 3.67% recorded in Q1 of 2022. After a period of steadily weaker growth, reaching 0.5% in Q4 last year, the economy has gradually picked up steam again.

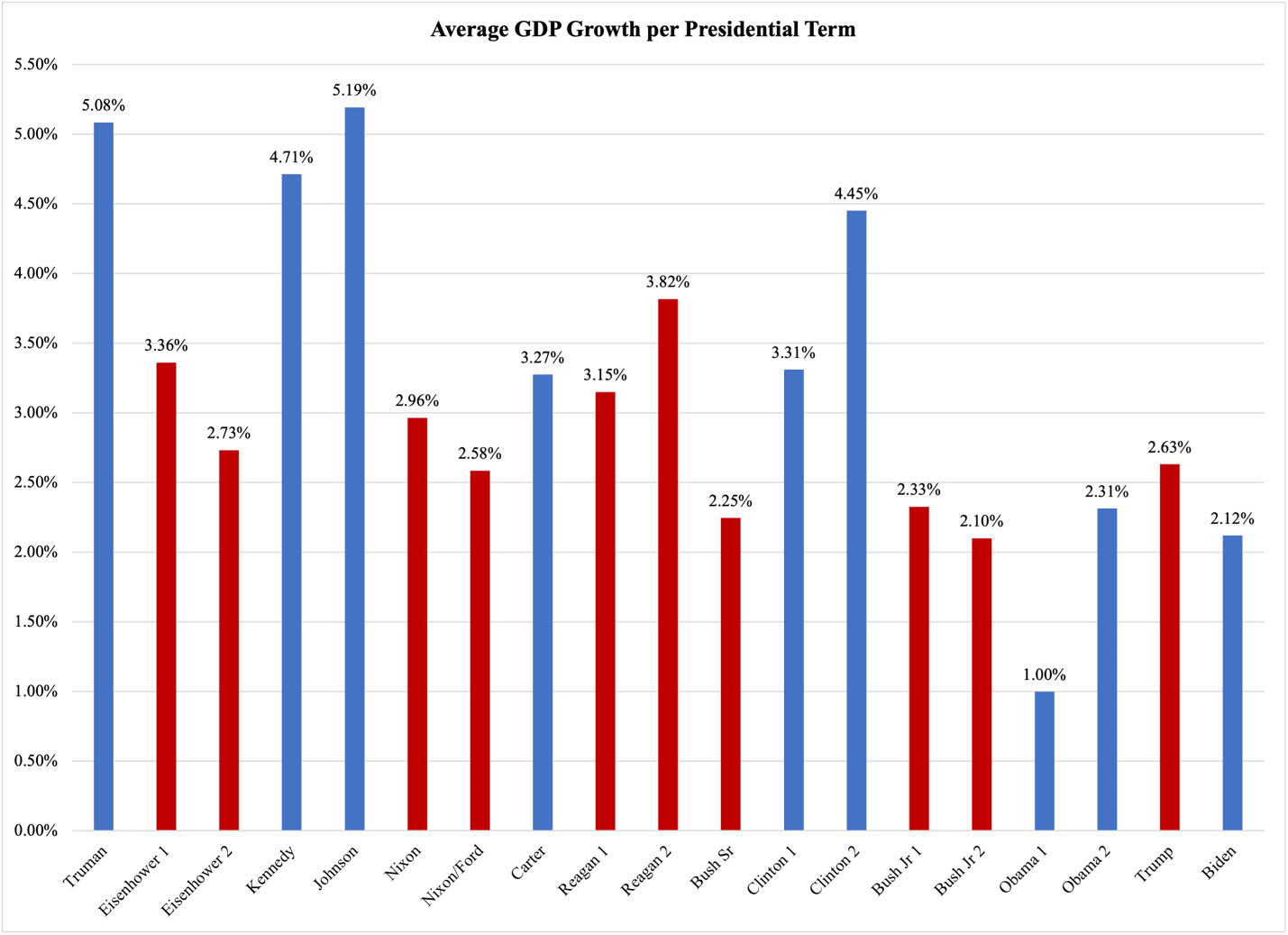

The 2.67% figure is by no means a spectacular growth rate: although no president since the turn of the century has averaged 3% GDP growth during any of his terms, that was common in the last century. Back then, growth rates in the 2-3% bracket were consistent with recessions, as when George Bush Sr. was president.

Figure 1 compares the presidential terms since Truman. In order to adjust for the distortions from the 2020-2021 artificial economic shutdown, I have removed 2020 from Trump’s term and 2021 from Biden’s term. The lockdown happened during Trump; the opening-up took place after Biden had been sworn in.

It is questionable from a strict analytical viewpoint to remove years like this from a time-series analysis; frankly, I can never remember seeing anyone do this in a context similar to this one. However, if we leave those two years in the analysis, President Trump’s average would be one percentage point lower than it is now. By the same token, Biden’s about 1.5 percentage points higher than he currently is. Since the cause of this is entirely man-made—government edicts to businesses to stop doing business—there is no period in recent history that compares to this one.

Since we are talking about de facto totalitarian policies governing the economy, thus prohibiting the market forces to operate properly, it is only fair to neutralize the effects of 2020 and 2021 on the current analysis.

With that in mind, we see a clear downshift in economic growth after the turn of the millennium:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Clear signs of business optimism

Looking at the components of GDP, we find more evidence of an economy that is doing no worse than it did in the 2010s. Private consumption grew at 2.5% in Q3, again the highest rate since Q1 of 2022. Purchases of durable goods, including but not limited to motor vehicles, were up 4.6%, a welcome increase compared to earlier this year when the growth rate was just a hair over 1%, and 2022, when it increased 2.3% in Q1 and fell for the rest of the year.

Gross fixed capital formation, a.k.a., business investments, is the best gauge of where the economy is heading. After a strong peak in 2021, with 14.4% increase in Q2 and 7.3% in Q3, spending under this category weakened steadily through 2022 and the first half of 2023. After three quarters with negative growth and an 8.5% decline from the peak point in Q2, 2022, business investments started turning around in Q2 this year. That quarter was not enough to increase capital formation on a year-to-year basis, but in Q3, the volume of business investments was 0.6% higher than a year earlier.

The turnaround in capital formation is a seal of approval for the U.S. economy. It is particularly encouraging to see that businesses have accelerated investments in structures. From Q4 2021 through Q3 2022, businesses reduced structural investments on a year-to-year basis. In Q4 2022, they increased spending in this category by 0.8%. Since then, the yearly growth rate has continued to increase, reaching 13.1% in Q3 this year.

In inflation-adjusted numbers, businesses are now building offices, warehouses, manufacturing plants, garages, and other structures for the same amount of money as they did in the economically very good 2019.

As expected, they have scaled back investments in equipment while expanding their facilities. These two variables are often one another’s opposite: when businesses have built new structures, they need to fill them with equipment, whereupon spending in this category increases. By the same token, given that the economy remains strong, when their buildings are filled to the brim, they scale back on equipment purchases and go back to building more structures.

However, equipment purchases are not down by much: -1.8% in Q3 over the same quarter last year. This is the first decline in this category of business spending since early 2020, in itself a seal of approval of the economy over the last two years.

Only one category of capital formation still needs improvement: residential home construction. Spending on the building of new homes has been shrinking since Q1 2022; in Q3 this year, total inflation-adjusted residential construction amounted to $195 billion. This is not even $5 billion more than the same number from 2019 (all in 2017 prices). Inbetween, there was a peak from late 2020 through early 2022 when residential construction topped $220 billion per quarter, again adjusted for inflation.

The good news about home construction is that the actual figures are going up: from $163 billion in Q1 this year to $195 billion in Q3.

The challenges ahead

All in all, the private sector of the U.S. economy is doing well, despite higher interest rates and an inflation rate that should be at least one percentage point lower than it is today. The good news, though, is that it looks like the monetary inflation has been whipped out of the economy by the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes; money supply has tightened sufficiently to largely eliminate the monetary inflation gap in the economy.

Remaining inflation is attributable in part to the relatively strong economy—unemployment remains below 4%—and in part to workers seeking and obtaining compensation for the high inflation we have just experienced. The United Auto Workers, UAW, have reached tentative contracts with Ford, GM, and Stellantis (Chrysler), which makes for a good case in point. Although real wages on average have not fallen during the inflationary episode, they also did not rise by much, and there are of course significant differences between industries in terms of how well employee compensation kept up with the price hikes.

With all this relatively good news in mind, the U.S. economy faces three challenges, each of which is strong enough to derail the economy:

- Government spending and debt.

According to the BEA’s latest national-accounts update, government spending increased by a total of 4.3% from Q3 last year to Q3 this year. To make matters worse, the increase is accelerating: it was 0.9% in Q4 last year, 2.9% in Q1 this year, and 3.65% in Q2. At the same time, the national debt stands at $33.6 trillion, up by $150 billion in October alone. This completely unsustainable debt trend will cause a fiscal crisis in America, and sooner rather than later. When it does, it will have serious, lasting consequences for the U.S. economy. - A wage-inflation spiral.

I am always cautious about bringing this up, because modern macroeconomic research—especially out of Scandinavia—is so narrowly focused on the interaction between wages and prices as an explanation of inflation that they cannot fathom any other reason for prices to rise. Their focus on wages as a cause of inflation is downright unscientific, but that does not mean wage increases do not contribute to price hikes. They do, and in a situation like ours, when workers want to compensate for real or perceived real wage losses, that link is particularly relevant. Hopefully, the U.S. economy will be dynamic enough to absorb the wage shock that is likely to follow in the footsteps of the new UAW contract. - Continued de-dollarization of global trade.

This is a process that has only just begun and probably will not be consequential for the U.S. economy for yet another couple of years. However, that ‘probably’ is crucial: depending in part on the outcome of the war in Ukraine, the move of global trade off the dollar could accelerate with a Russian victory or decelerate with a Ukrainian surge. Since the former is the more likely path for the conflict, the dollar could be in for a jolt of de-dollarization instability in the early part of 2024.

Barring any external shock, the American economy is going to do well through the fourth quarter and into the start of next year. The only real cloud on the horizon is that which emanates from Congress: despite his conservative ambitions, newly elected Speaker of the House Mike Johnson is unlikely to make any progress on restoring fiscal responsibility on Capitol Hill. What that means for the risk of a fiscal crisis in America is an issue we will most certainly return to in the near future.