For more than a quarter century, the fortunes of the United States and China were fused in a uniquely monumental joint venture.

Americans treated China like the mother of all outlet stores, purchasing staggering quantities of low-priced factory goods. Major brands exploited China as the ultimate means of cutting costs, manufacturing their products in a land where wages are low and unions are banned.

As Chinese industry filled American homes with electronics and furniture, factory jobs lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese from poverty. China’s leaders used the proceeds of the export juggernaut to buy trillions of dollars of U.S. government bonds, keeping America’s borrowing costs low and allowing its spending bonanza to continue.

Here were two countries separated by the Pacific Ocean, one shaped by freewheeling capitalism, the other ruled by an authoritarian Communist Party, yet conjoined in an enterprise so consequential that the economic historian Niall Ferguson coined a term: Chimerica, shorthand for their “symbiotic economic relationship.”

No one uses words like symbiotic today. In Washington, two political parties that agree on almost nothing are united in their depictions of China as a geopolitical rival and a mortal threat to middle-class security. In Beijing, leaders accuse the United States of plotting to deny China’s rightful place as a superpower. As each country seeks to diminish its dependence on the other, businesses worldwide are adapting their supply chains.

Chimerica has yielded to a trade war, with both sides extending steep tariffs and curbs on critical exports — from advanced technology to minerals used to make electric vehicles.

American companies are shifting factory production away from China to less politically risky venues. Chinese businesses are focused on trade with allies and neighbors, while seeking domestic suppliers for technology they are barred from buying from American companies.

Decades of American rhetoric that celebrated commerce as a wellspring of democratization in China have given way to resignation that the country’s current leadership — under President Xi Jinping — is intent on crushing dissent at home and projecting military might abroad.

For Chinese leaders, the once-prevailing faith that economic integration would undergird peaceful relations has been relinquished to a muscular form of nationalism that is challenging a global order still dominated by the United States.

“In a perfect political world, these are two countries that are made in heaven, exactly because they are complementary,” said Yasheng Huang, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management. “Essentially, these two countries kind of got married without knowing one another’s religions.”

But divorce is not a practical option. The United States and China — the world’s two largest economies — are intertwined. Chinese manufacturing has evolved from basic areas like footwear and apparel into advanced industries, including those central to efforts to limit the ravages of climate change. The United States remains the paramount consumer marketplace. Even as geopolitical tensions fray their ties, these two countries still depend on each other, their respective roles not easily replaced.

Apple makes most of its iPhones in China, even as it has been shifting some production to India. A Chinese brand, CATL, is the world’s largest maker of electric car batteries, and Chinese companies dominate the refining of critical minerals like nickel used in such products. Chinese businesses make up more than three-fourths of the global supply chain for solar energy panels.

China is a leading source of sales for major global brands, from Hollywood studios and multinational automakers to manufacturers of construction equipment like Caterpillar and John Deere. Computer chip-makers like Intel, Micron and Qualcomm derive roughly two-thirds of their revenues from sales and licensing deals in China.

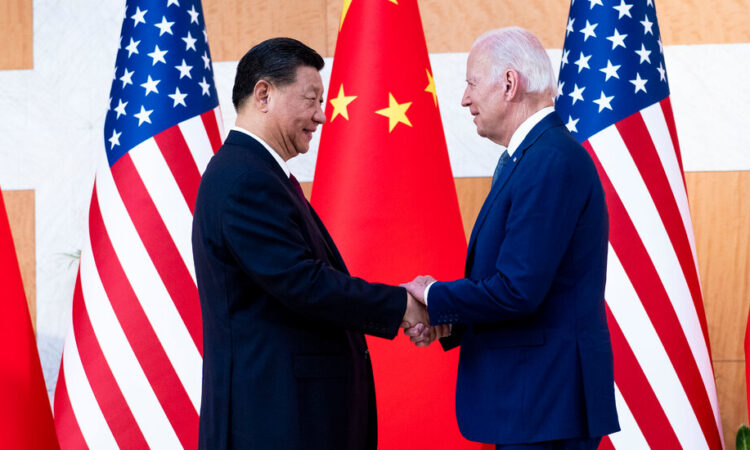

The powerful tug of those commercial entanglements will be in the background of planned discussions on Wednesday between Mr. Xi and President Biden. The meeting, at a global conference in San Francisco, would be their first in a year.

It was never going to last.

Still, the prospect that their political schism will endure is altering global supply chains. In place of relying on China as the factory floor to the world, businesses are increasingly exploring ways to diversify. Mexico and Central America are gaining investment as companies that sell to North America set up factories there.

Some trade and national security experts celebrate these shifts as an overdue adjustment to decades of growth propelled by a perilous codependency between the United States and China.

Beijing’s purchases of American debt — though steadily declining since 2012 — kept borrowing costs low, but also encouraged investors to seek out greater returns. That led financial speculators to gorge on low-grade mortgages, delivering the global financial crisis of 2008, said Brad Setser, a former U.S. Treasury Department official and now an economist at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It was certainly a form of interdependence,” Mr. Setser said. “But the notion that China saves and the U.S. spends, China lends and the U.S. borrows, and all is good because we are two sides of the same coin, we’re complementary, that was never sustainable.”

The pandemic brought home the risks of American reliance on Chinese factories to produce vital goods like masks and medical gowns, to say nothing of exercise bikes and smartphones, all of which became scarce. Chaos at ports and increases in shipping prices exposed the pitfalls of leaning on a single country on the other side of an ocean.

The Biden administration took the disruption and growing rivalry with China as impetus for an industrial policy aimed at encouraging American manufacturing and greater trade with allies — especially in strategically vital industries like computer chips.

Yet economists caution that even a marginal shifting of factory production from China will entail higher costs for consumers while slowing global economic growth.

The share of American imports from China has dropped 5 percent since 2017. The goods imported from other countries are more expensive — 10 percent more in the case of Vietnam, and 3 percent higher from Mexico, according to research by Laura Alfaro at Harvard Business School and Davin Chor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business.

Though wages have risen in China, no other country possesses the depth and breadth of manufacturing capacity.

That did not happen by accident.

How China came to bet on trade.

Beginning in the late 1970s under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese government sought to rescue the country from its state of poverty and isolation by unleashing a series of market reforms. National wealth would be amassed by making products and selling them to the world. Officials courted foreign investment while building out infrastructure — highways, ports, power plants.

The culmination came in 2001 when China joined the World Trade Organization, winning global access for its exports in exchange for promising to open its own markets to foreign competitors.

American leaders championed China’s inclusion in the global trading system as far more than an effort to sell Big Macs and bulldozers to the world’s most populous nation.

“By joining the W.T.O., China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products,” President Bill Clinton declared on the eve of a key congressional vote in 2000. “It is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom.”

Yet beneath such high-minded rhetoric, American brands pushed for greater access to China for the simple reason that its factories could turn out goods more cheaply than anywhere else.

“China makes products that working families can afford,” said Clark A. Johnson, chief executive of the then-prominent chain Pier 1 Imports, as he represented the National Retail Federation during congressional testimony in 1998.

That formulation carried the day.

In the two decades after China became part of the W.T.O., American imports from China multiplied fivefold to $504 billion a year, according to census data.

Walmart, a company ruled by a zeal for low prices, opened a procurement center in the boomtown of Shenzhen. The company would gather hundreds of representatives from surrounding factories. They would sit in wooden chairs, sipping tea out of flimsy plastic cups, as they waited for hours to meet Walmart’s buyers. The company could demand rock-bottom prices, aided by the implicit threat that if one factory balked, another could be summoned from inside the same waiting room.

Two years after China entered the W.T.O., Walmart was spending $15 billion on Chinese-made products, a sum that encompassed almost one-eighth of all of China’s exports to the United States. A decade later, Walmart was importing $49 billion of Chinese goods into the United States, according to one analysis.

Gaining from this trade was virtually anyone walking into a store. Chinese imports effectively boosted the spending power of the average American household about 2 percent, or $1,500, a year from 2000 and 2007, according to one study. Chinese goods pressed down American prices 0.19 percent a year from 2004 to 2015, another study found.

The people left behind.

Those hurt by Chinese imports were concentrated and conspicuous. Once-thriving American factory towns sank into joblessness and despair, swapping restaurants and hardware stores for food banks and pawnshops.

From 1999 to 2011, a surge of low-priced Chinese imports eliminated nearly one million American manufacturing jobs and two million positions throughout the broader economy, according to a paper by the economists David H. Autor, David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson.

The resulting anger helped deliver Donald J. Trump to the White House. During his 2016 campaign, he vowed to unleash a trade war.

“We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country,” Mr. Trump said at a rally. “It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world.”

Such inflammatory characterizations collided with the reality that low-priced goods from China were an antidote to the rising cost of living. Still, Mr. Trump’s accusations resonated in many working-class communities.

There was truth to the notion that Chinese industry was breaching the rules of international trade. The government lavished credit on the largest companies via loans from state-owned banks. Chinese industrial ventures could evade environmental and labor laws by sharing a cut of the profits with local officials. The Chinese market remained full of barriers to competition from foreign companies. Those that invested in China suffered brazen theft of intellectual property and rampant counterfeiting of their products.

Yet in many ways, the United States benefited from trade with China. Cheaper goods helped households cope with stagnating incomes while padding corporate coffers. The trouble was that most of the gains flowed to the shareholders of companies making products in China, while Washington failed to cushion those left behind.

A federal program called Trade Adjustment Assistance was supposed to compensate those rendered jobless by cheap imports, offering cash and training for other work. But Congress vastly underfunded the program. Fewer than one-third of those eligible for benefits in 2019 received help, according to an analysis of Department of Labor data.

In a triumph of simple political messaging over the complex accounting of trade, the public increasingly came to believe that Chinese industry was solely a predatory force — that Americans “were just taken advantage of,” said Jessica Chen Weiss, a China expert at Cornell University and a former State Department official in the Biden administration. “We didn’t do a good job of distributing the benefits, but they were nonetheless real.”

Part of the change in American sentiment appeared to reflect bitterness over how engagement with China failed to deliver the promised political transformation.

The Chinese government used its trade winnings to expand its military capabilities, while menacing neighbors like the Philippines. It constructed an Orwellian surveillance apparatus, wielding it against the Uyghurs, an ethnic minority in the western region of Xinjiang.

American trade with China also failed to promote Beijing’s promised market reforms. Instead, Mr. Xi’s government has amplified the power of state-owned companies, while cracking down on the private sector.

For decades, foreign automakers were forced to team up with state-owned car companies as a way to get a crack at the Chinese market. Now, a fresh crop of Chinese companies is harnessing the know-how gleaned from those ventures to take markets from foreign automakers.

In the end, the engagement policy led to the moment at hand: a messy and bewildering process of disengagement.

The Biden administration argues that, by reducing dependence on Chinese industry, the American economy will become more resilient and less vulnerable to disruption in the face of shocks and conflict.

But many factory goods made in countries like Vietnam contain large volumes of parts and materials produced in China, according to research by Caroline Freund, an international trade expert at the University of California, San Diego.

As Chimerica dissolves, the world could end up with greater complexity in its supply chains — more factories in more countries — yet still reliant on critical components made largely in just one.

“You still depend on China, it’s just that it takes more steps along the way,” said Mr. Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations. “There’s more places where things could go wrong.”