What explains the establishment’s obsession with Brexit as the cause of all the UK’s economic ills? Whether it is the BBC or the Financial Times, the Economist, CNN, the Guardian, The Times or Bloomberg, all of them are absolutely certain not only that Brexit has damaged the UK economy, but that everything was fine and dandy until 2016 and the vote to leave the European Union.

Whilst I have always agreed that leaving the EU single market and customs union comes at a financial cost — about 1-2 per cent of GDP — I have also written extensively on where these publications either misrepresent data to imply a non-existent Brexit economic effect, or ignore data which does not support their argument, or fail to report data which overturns their previous arguments entirely.

It would be mildly amusing if it wasn’t for the fact that this “blame Brexit” obsession has a very serious side effect. It is diverting people from looking at the actual and very real economic issues the UK does face.

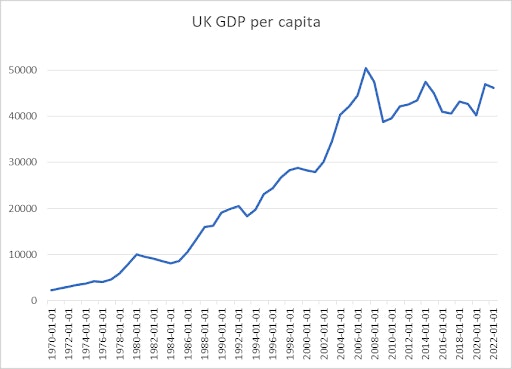

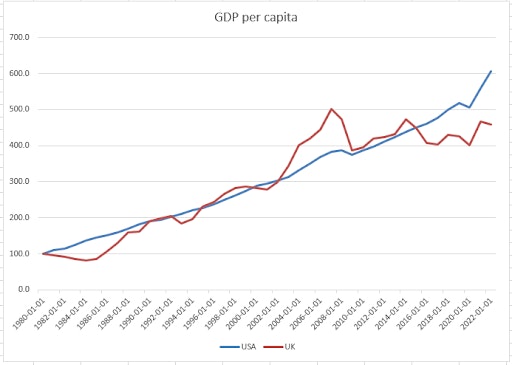

Take this chart of UK GDP per capita in current US dollars:

It is clear from this chart that UK GDP per capita has stalled since the Great Financial Crash of 2008 (I would actually argue it began earlier but was hidden by the pre 2008 bubble — but that is for another time).

Surely people should be concerned about what has caused UK per capita GDP to stall for 15+ year’s right? Wrong. Instead they spend their time talking only about how GDP per capita growth compares to the USA since — you guessed it — Brexit.

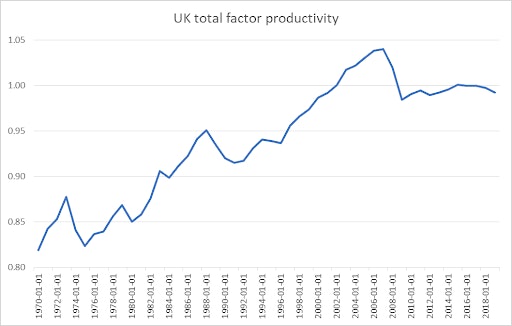

Or what about this chart of UK productivity.

As with GDP per capita, it clearly shows productivity first crashing in 2008 and flat lining ever since (again I would argue this began earlier but was masked by the pre 2008 bubble).

The experts must be talking about this? Nope. Once again the establishment analysis is all about Brexit. In the case of the FT, about “the productivity headwinds from the entry into force of the UK’s post-Brexit trading rules”.

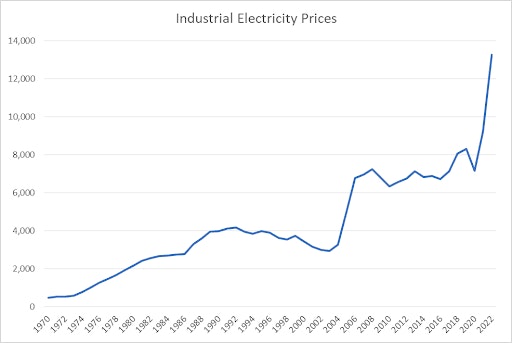

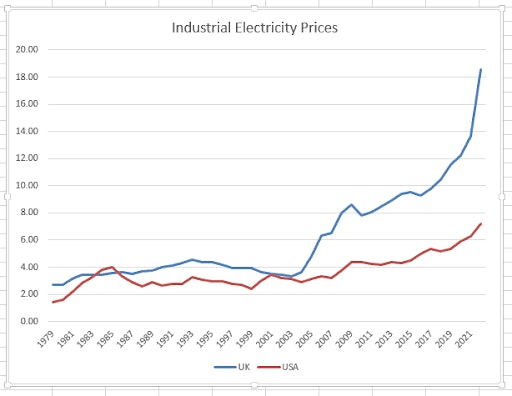

How about this chart of UK industrial energy prices. It is quite clear that prices started to rise in 2003, doubled in three years and nearly tripled before the vote to leave the European Union. Surely that gets some attention? Surely someone out there is asking whether there may be some connection between rapidly rising energy prices, productivity and GDP growth?

Wrong again. As with everything else, the only thing that matters when it comes to energy costs is Brexit and pretending the dash to net zero is not the cause of the rise.

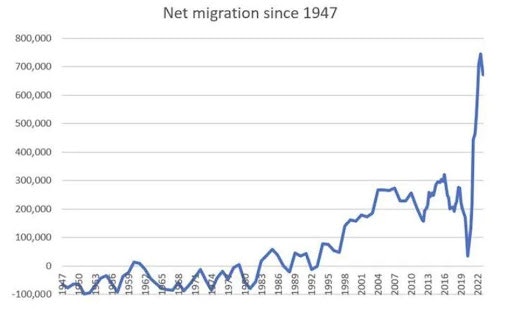

Immigration? Surely someone out there is looking at the historically unprecedented explosion in net migration into the UK and asking if it might have had an effect on productivity and per capita GDP?

By now, I am guessing you know the answer to that. After the vote to leave the EU, all immigration analysis concentrated, at first, on how Brexit would destroy the UK economy by reducing immigration and then later — when immigration exploded — on how Brexit had failed as a project because immigration had not been reduced.

We are told that Brexit has reduced the UK economy by 5 per cent, justified by various doppelganger models which show the UK economy performing much closer to the rest of Europe since the referendum than to the USA. In short, the proof of a Brexit effect is how UK GDP has underperformed versus history compared to America.

But why do the modellers not ask why that might be? When it started? And what else might be the cause? For example, perhaps the fact that UK GDP per capita has flatlined since 2008 whilst the US has powered on might be an important factor?

Or perhaps the fact that UK industrial electricity prices decoupled from the USA in 2003, and especially and radically so since 2016, might explain a little of the economic divergence?

And what about post-Covid fiscal stimulus?

In March 2021 the USA began implementing an unprecedented $1.9 trillion stimulus package — equivalent to two thirds of UK’s annual GDP — heralded as adding as much as 3 per cent to US (and 1 per cent to global) GDP. As the FT reported at the time, in comparison to the almost non-existent fiscal intervention in Europe the “US stimulus package leaves Europe standing in the dust”.

So, surely someone must be asking if this US fiscal stimulus might explain even a modicum of the very different GDP outcomes between the US and the UK since Covid (and the end of the transition period). Anyone?

The establishment response to all things economic remains that everything was fine and dandy until 2016 and the vote to leave the EU — or, for some, fine and dandy until January 2021 and the end of the transition period. You see, Brexit is the problem and re-joining the EU (or at least the single market and customs union) is the solution.

It doesn’t matter that even a cursory look or understanding of the data shows our economic problems long predate even the rise of UKIP let alone the referendum to leave the EU. It doesn’t matter that the data shows that high energy prices and unlimited, historically unprecedented mass immigration seem to have “coincided” with the collapse in productivity and GDP per capita.

Nope, the only “mistake” was leaving the EU. A decade or more after these problems became noticeable.

And the establishment solution? Well, apart from re-joining the EU single market and customs union naturally, that’s easy. More and more mass immigration. More and more intermittent renewables — and hence energy prices — and more passing of decision making to unelected international institutions.

Some people claim that the establishment has run out of ideas. But that’s not it at all. The issue isn’t a lack of ideas. It’s that the ideas they have — the same ideas and policies they have been pursuing for decades — are what got us into this mess in the first place. And it doesn’t matter who you vote for — as I explained here, all party’s “solutions” are broadly the same.

There is no doubt that the UK has serious and significant economic problems. It is also abundantly clear that these very real issues significantly predate Brexit. Continuing to blame Brexit for all economic ills is not just fallacious but — far more importantly — removes attention and analysis from the real causes. Without understanding those, we have no hope of finding the real solutions.