The repeal of fiscally conservative banking legislation and the trading of complex financial instruments since the ‘Big Bang’ has led to astronomical profits in the banking sector. Many years on and several financial crises later, the economic conditions in communities across the country have seldom been so dire. The underlying neoliberal economic model is clearly broken. Could encouraging a return to a ‘first-principles’ model of localised economic growth in the real economy herald the promise of a revolution in the way we stimulate growth?

Aside from wrecking the macroeconomic frameworks that form the basis of a stable and equitable society, the government’s understanding of how organisations work (microeconomics) and the ability to generate sound monetary and fiscal policies that create a sound platform for productivity is minimal. Consequently, we are living in a high-stress society that is on trajectory to enter the same basket-case territory as Zimbabwe or Venezuela.

Reimagining banking policy from the ground up

Despite the glum prognosis, crossing this threshold presents an opportunity to rebuild our society, community by community, municipality by municipality and city by city. The first step is to stabilise our local economies, and this should begin by daring to rethink the role of banking.

It seems clear perhaps to everyone except some politicians and bankers that the big banks have ceased to work in the best interests of communities and that their business models have become increasingly unstable.

Northern Rock

The rot had begun in the UK in 2007 a little-known bank in the North East, Northern Rock, became the first major banking failure when it overextended, and the Bank of England was unable to help as it was hamstrung by chancellor Brown’s inflation target. Other banks followed in 2008, culminating in the collapse of the giant US investment bank, Lehman Brothers, overnight, and seven major UK banks trembling on the brink. Tales of ineptitude, greed and arrogance exposed the failure of leadership of the national banks.

The government stepped in and spent £137bn pounds to save the British banks – note, not to save the shareholders or the customers, but the banks. So, the culprits were rescued because they were deemed ‘too big to fail’, and the victims punished. In the USA in 2008 alone, 3.1 million Americans filed for foreclosure, which meant losing their homes.

Such are the vagaries of politicians when it comes to monetary policies.

Demutualisation

The real tragedy was that Northern Rock had been for some time once of the most admired building societies in the UK, an icon in the North East. Its name adorned the shirts of both the Newcastle football and rugby clubs. It had been a building society – that is, a mutually owned savings and mortgage entity, and had successfully amalgamated 53 other building societies and mutuals in the previous 40 years, with up to a million savers and 270,000 borrowers, almost exclusively in the North East.

However, the board decided it should become a retail bank, go public and trade on the stock market. It seemed, financially, to be a good decision. In 1997 it demutualised and scaled the heights of the FTSE 100, the elite club of Britain’s biggest quoted companies, and in the process became the fourth biggest bank in the UK by share of lending.

In the nine years from June 1998 (the first year after demutualisation) to June 2007 Northern Rock’s total assets grew from £17.4bn to £113.5bn. But a few months later, out of the blue, it collapsed, with the loss of 2500 jobs. The sub-prime mortgage contagion in the securitisation market had caused the first run on a UK bank in 140 years; a terrible loss for the staff, lenders and savers, and the region.

People or profit

“But I have this against you: You have abandoned your first love. Therefore, keep in mind how far you have fallen.” These words from the book of Revelation sum up the entire banking crisis of 2008. What was Northern Rock’s first love? Mutuality. Northern Rock arose from a 1965 merger of Rock (1865) and Northern Counties Permanent (1860) building societies. Both were originally established to provide mortgages to an industrial workforce that remained for the most part underpaid and close to poverty.

These mutual societies also acted as a cooperative endeavour that fitted well with the beginnings of union movements and the call for democracy in British government. The building society offered a measure of protection to its members as well, particularly during the massive economic fluctuations that marked the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. These were the values that had made the company such a success as a building society.

If the aim of becoming a retail bank creates such a distortion away from the customer/community focus that characterised the mutuals what does that say about banks in general? Are they, in this mould, an asset to society? Are they really contributing to the nation’s wealth, or as John Ruskin would have it, to the nations ‘illth’? Already, today investors and customers are in a flutter about the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank in the US and, in Europe, the shakiness of Credit Suisse. According to economist, Anne Pettifor, there is more to come.

A better banking model

It is long past the time to review the role of banks in society. Is the financialisation of the British economy adding to the real wealth of society? First-principle questions beg to be asked. Here is an illustrative historic example: in 1903, Henry Ford’s lawyer was advised not to buy stock in Ford. “The horse is here to stay,” he was told by the bank president. The lawyer disregarded the bank’s advice and bought $5,000 worth of stock – he sold it in 15 years later for $12.5mn. Banks and the community will only flourish if they return to their ‘first love’ – investing to serve society and not Mammon.

Today, if we want – according to first principles – healthy communities and towns, we need to substitute the church for a local bank. Our major issue today is the problem of debt and the lack of productive capital. What we do not need is a political life that is ruled by a ruinous financial system and avaricious national banks.

A solution from ‘the land of Mammon’?

Where is the best example of a bank that serves society? Of all places, in the USA, the Bank of North Dakota (BND), which, in 2014, while our politicians were debating the role of banking, had one branch, no automated teller machines and not a single investment banker.

North Dakota, with a population of 680,000 has 77 banks and 427 branches. Sheffield, which has a slightly lower population has 17 banks and 53 branches – and shrinking. Thus, North Dakota has four times as many banks and eight times as many branches per 100,000 people as Sheffield! Guess who gets the better service?

The reason is that North Dakota is the only state in the USA that has established a publicly owned bank, i.e., by the State government. Founded in 1919, the Bank of North Dakota’s mission is to “promote agriculture, commerce, and industry and be helpful to and assist in the development of… financial institutions… within the State”.

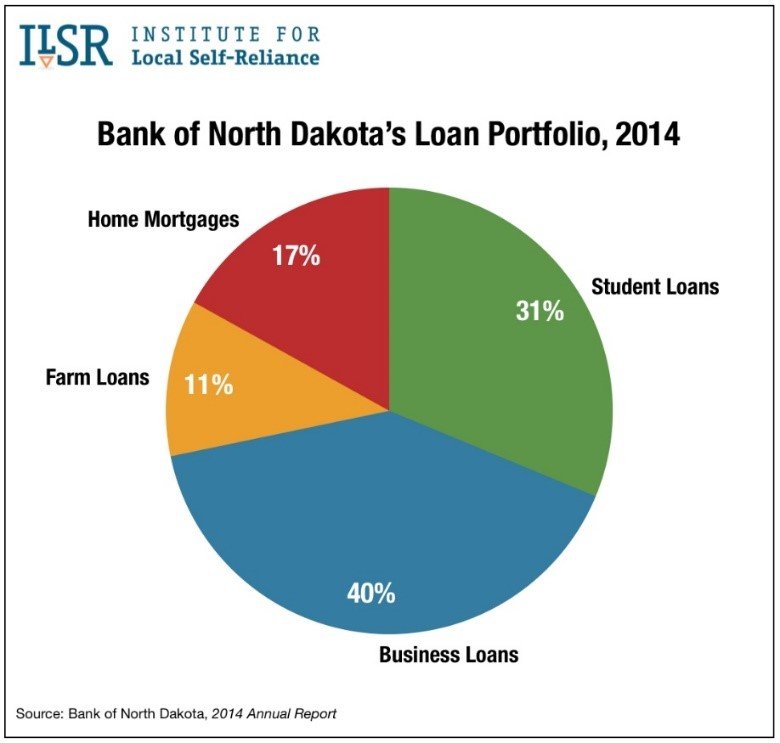

BND functions mainly as a ‘banker’s bank’ – meaning that most of its lending is done in partnership with local banks and credit unions. About half of the bank’s loan portfolio consists of business and agricultural loans that are originated by a local financial institution and funded in part by BND. By participating in these loans, BND expands the lending capacity of North Dakota’s community banks, giving them added strength in competing against big out-of-state banks.

At a time when many students leave college burdened by high-interest rate loans, BND offers some of the lowest student loan rates in the country.

Serving the community.

Thanks in large part to BND, community banks are much more numerous and robust in North Dakota than in other states. While locally owned small and mid-sized banks and credit unions (those under $10bn in assets) account for only 29% of deposits nationally, in North Dakota they have a remarkable 80% of the market.

The bank’s mission is promoting economic development, not competing with private banks. “We’re a state agency and profit maximization isn’t what drives us,” says bank president Eric Hardmeyer.

By their fruits shall they be known

By helping to sustain a large number of local banks and credit unions, BND has strengthened North Dakota’s economy, enabled small businesses and farms grow, and spurred job creation in the state, not least by financing major infrastructure projects.

But is it profitable?

According to the Wall Street Journal it was more profitable than the Goldman Sachs Group, has a better credit rating than JP Morgan Chase & Co and hasn’t seen profit growth drop since 2003. In its 2019 annual report, the BND reported its sixteenth consecutive year of record profits, with $169mn in income, just over $7bn in assets, and a hefty return on investment of 18.6%.

Finally, going back to the Northern Rock collapse, while all the other US state treasuries were submerged in red ink after the 2008 financial crash, one state’s bank outperformed all others and actually launched an economy-shifting new industry – the BND.

There is a central conclusion to be drawn, a public banking model, if set up correctly – and ethically – can be more efficient and more profitable than the private model. Profits are invested into the local community rather than secreted away in tax havens and used to pay exorbitant bonuses.

Imagine what economic life might be like if Yorkshire set up a publicly owned bank along the lines of the Bank of North Dakota, with the same values.

John Carlisle will be making the case for ‘Where Real Economics beats Neoliberalism’ at the Festival of Debate, Sheffield on Tuesday 9 May, 2023.

Sheffield: Where Real Economics Beats Neoliberalism | Festival of Debate