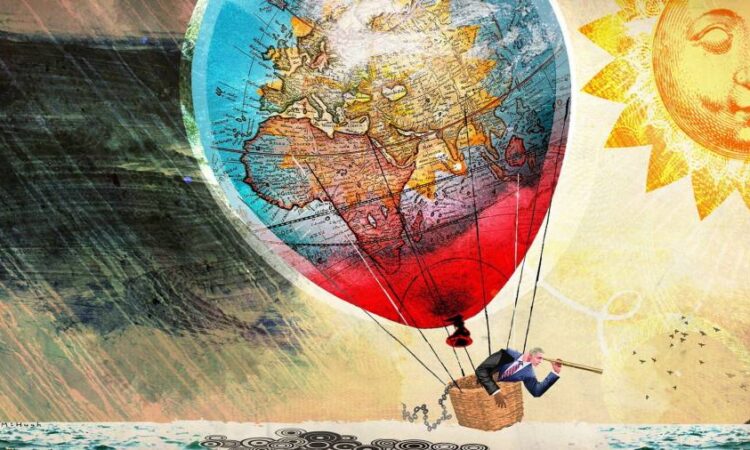

Having listened to many officials and government ministers speaking about the global economy in recent months, I have sensed their visceral fear of sounding complacent. The world is uncertain and fragmenting, they say. There are risks of a hard landing. Great power rivalries undermine prospects. We face a world of frequent adverse supply shocks. And things are so bad, we are living through a “polycrisis”.

The inevitable conclusion, everyone earnestly agrees, is that now is the time for vigilance. I fully understand why we are hearing this chorus of concern, for nobody wants to emulate the IMF’s spring 2006 global financial stability report. Shortly before the global financial crisis, Gerd Häusler, then the fund’s director of international capital markets, said that stability in financial markets was “as good as it gets” with “sharply improved resilience”. It was an honest assessment, but catastrophically wrong.

Nevertheless, I have great sympathy for Häusler’s decision to describe the global economy accurately rather than cover his back. So, in this spirit, it is important to note that the global economy in 2023 has so far gone pretty well and much better than feared. Here are five important reasons to be cheerful.

If you look at the world’s largest economies — China, the US, the EU, India, Japan, the UK and South Korea — none is in recession (contrary to predictions) at a time when the Federal Reserve has raised US interest rates five percentage points. That is unusual and positive, said Adam Posen, head of the Peterson Institute of International Economics. The resilience in almost 70 per cent of the global economy alongside the absence of any financial distress in large emerging economies makes a system-wide financial crisis unlikely, he told me. Why then is there so much gloom around? “We’re all scared of sounding arrogant and overconfident,” Posen said.

The second reason to be happier about the global economy stems from one of the often repeated weaknesses — that the world is suffering from a series of adverse supply shocks. That is true, but shocks wane as well as wax. Global difficulties in moving goods are fast disappearing, with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s supply chain pressure index now well below its historical average. In a separate indicator, a Kiel Institute tracker of the proportion of freight on stationary container ships waiting to get into ports is now also back to normal levels.

Europe, specifically, can welcome a positive shock in lower natural gas prices. The speed and solidarity of its response to Vladimir Putin’s natural gas blackmail over the winter ensured no one froze, the lights stayed on and energy consumption fell significantly. All of this came without a recession. Compared with December’s forecasts from the European Central Bank, the current market price of gas over the next three years is more than 70 per cent lower, and almost 10 per cent lower than the central bank’s March forecasts. Sustainably lower gas prices than feared at the start of this year will allow Europe to have higher incomes, higher consumption and lower inflation, making the ECB’s task easier.

If the data has been broadly resilient, no one should be naive about the economic risks of the increasingly strained political relationship between China and the US. Mutual antagonism has the potential to split the world into trading blocs, forcing nations to take sides and duplicating production with huge inefficiencies. But the latest moves — notably speeches from Janet Yellen, US Treasury secretary, and Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission president — have sought to reassure China that neither is trying to decouple its economy from the world’s largest manufacturer, nor stop China’s path to prosperity. Encouragingly, Yellen’s remarks were echoed by Jake Sullivan, Joe Biden’s national security adviser, on Thursday. This is progress and lowers a big risk.

China’s emergence from its zero-Covid policy provides the fourth reason to look at 2023 with some optimism. Its economy grew at an annual rate of 4.5 per cent in the first quarter, faster than expected, with household consumption and domestic services leading the way. Although IMF officials this month chose to stress negative aspects of this rebalancing, higher Chinese domestic consumption is exactly what the global community has asked of Beijing for decades. It raises living standards, reduces the chances of an over-investment crunch and gives Chinese people more to lose if their government decides on a path of military aggression.

The final reason for cheer is slightly parochial to oil-importing economies. At the start of this month, the Opec+ nations agreed to cut oil production by 1mn barrels a day, sending the Brent crude oil price climbing from about $77 a barrel to $85 immediately. It demonstrated a confident oil cartel, willing to pursue a Saudi-first policy at the expense of its customers around the world. The oil price has now sunk back to $77 a barrel. As a consumer-facing a cartel, there is nothing better than seeing it either unable to enforce its production quotas or unable to control the global price. Weakness in Opec+ is good for oil consumers and the global economy.

There is no doubt that 2023 will provide further economic hiccups. Further banking stress, a US political impasse over its debt ceiling and persistently high core inflation are significant risks. But the year has started well, certainly better than expected. The global economic landscape in 2023 right now is pleasantly surprising. That is something to celebrate.