I apply the assessment framework to the EU Car Regulations of 2009, and 2019, and to the Fit For 55 revision as part of the EGD. The 2014 Regulation will be analyzed to a limited degree due to its nature as an interim regulation specifying the modalities of one the 2009 Regulation’s standards. The EU has merged the Regulations on the CO2 emission standards of cars and light commercial vehicles (vans) from the 2019 Regulation onwards. However, as cars make up the bulk of light road transport and for the sake of comparability over time, I only focus on the provisions on passenger cars within the 2019 and Fit For 55 Regulations.

The Car Regulations establish binding CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars in the EU, usually in five-year intervals (2012, 2020, 2025, 2030, and 2035)32. These standards are set at the level of car manufacturers, rather than at the Member State level, and serve to assist Member States with reaching their nationally binding targets under the Effort Sharing Decision/Regulation (for more on Effort Sharing see ref. 33). Furthermore, the overall target is divided into individual targets for carmakers taking into account the average weight of their cars.

While many more legislative acts directly or indirectly relate to the emissions of cars, I take a focused approach investigating the Car Regulations because improving vehicle efficiency is seen as the main driver for reduced road transport emissions, not surprisingly due to the EU’s prioritization of this approach3. Nevertheless, road transport emissions are not only reduced by improving vehicle efficiency but also by reducing car use through avoiding journeys or shifting to lower-carbon transport modes, and by improving the efficiency of fuels3,29,34. As such, efforts to truly bring the EU car sector in line with the long term should also include spatial planning and behavioral measures to reduce demand. However, this entails a broader debate about what sustainable mobility means and a more thorough investigation of varying pieces of legislation on different policy levels from the local to the EU. As such, it falls outside the scope of this article.

Consistency of the Car Regulations’ objectives with long-term objectives

The 2009 Car Regulation set out two emission standards for new cars: (1) 130 g CO2/km by 2012; and (2) 95 g CO2/km by 202035. The target for 2012 was to be complemented by measures such as the use of biofuels that were projected to result in an additional reduction of 10 g CO2/km.

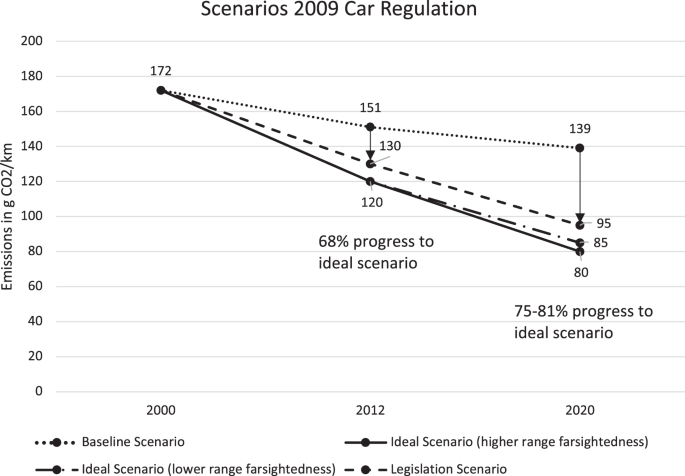

The 2009 emission standards closed the gap between the baseline and the ideal scenario by around 68 to 81% (see Fig. 1). Without any additional measures, average car emissions would be 151 g CO2/km by 2012 and 139 g CO2/km by 202027. Concerning the ideal scenario, few studies on the required car emission standards were published at the time of policy formulation. However, already in the 90 s, the car industry and the European Commission set a standard of 120 g CO2/km first by 2005, and later by 201215. Therefore, to not backslide prior ambition, the EU should ideally maintain the standard of 120 g CO2/km by 2012. If the emission standards continue to follow the linear emission reduction trajectory required to meet that standard, the 2020 standard would be around 85 g CO2/km. Furthermore, these standards align with the standards required to reach the economy-wide target of 20% emission reduction by 2020 compared to 1990 of the 2020 Climate and Energy Package. To be in line with that target, an emission standard correlating to 20% reduction compared to 1990 would have needed to be reached already in 2005. That way, the majority of all passenger cars—not only new ones—would emit 20% less emissions compared to 1990 in 2020. If the emission standards were to continue the linear emission reduction trajectory required to reach 20% by 2005, the standards would be around 120 g CO2/km by 2012 and around 80 g CO2/km by 2020. While it could be argued that these standards could lead to an overachievement of the 20% by 2020 target, stricter standards could compensate for the lack of standards until 2012, and hence the presence of more polluting vehicles in the fleet. Consequently, as Fig. 1 shows, the 130 g CO2/km by 2012 standard closed the gap with the ideal scenario by around 68% and the 95 g CO2/km by 2020 standard closed it by 75–81%.

Therefore, while the standards are close to what is required, they are inconsistent with the overall EU emission reduction objectives. Their inconsistency increased due to the flexibilities included in the legislation35. First, a gradual phase-in of the standards delayed the emission reductions until 2015. Second, the Regulation created a system of super-credits that resulted in an underestimation of manufacturers’ emissions. Super-credits give low- or zero-emission vehicles (ZLEV) a heavier weight when calculating a manufacturer’s average annual emissions and, by doing so, create a discrepancy between real-world and calculated emissions, in which the real-world emissions will be higher than the calculated average36,37. Therefore, the standards will be met on paper but not in reality. Furthermore, while the system of super-credits aimed at incentivizing the uptake of ZLEVs, in the long term it can be counterproductive as fewer ZLEVs are required to meet the standards.

The 2014 Regulation expanded these flexibilities by including a phase-in of the 2020 standard until 2021, and by extending the super-credits system until 202338,39. However, the use of the system is limited to avoid a large gap between real-world emissions and calculated emissions. Transport & Environment (T&E) and the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) have estimated that because of these flexibilities the actual 2020 standard would be closer to 100 or even 108 g CO2/km rather than 95 g CO2/km40,41.

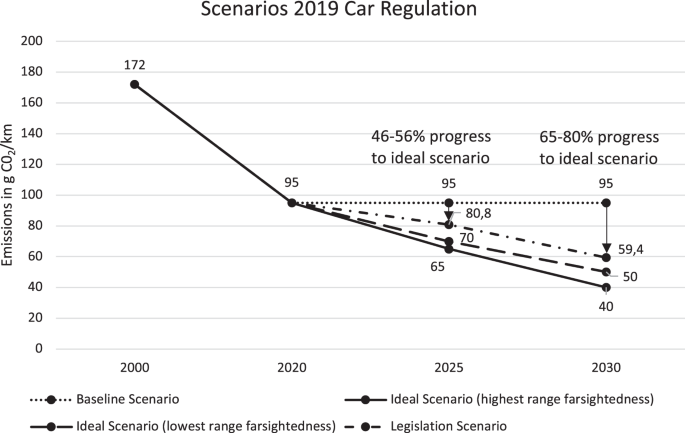

The 2019 Car Regulation established targets of a 15% reduction in g CO2/km by 2025 and a 37.5% reduction by 2030, both compared to a 2021 baseline. It also included benchmarks of a 15% share of ZLEVs of new passenger cars by 2025 and a 35% share by 203042. Until 2024, these efforts will be complemented by measures resulting in an additional reduction of 10 g CO2/km. Noticeably, the standards of the 2019 Regulation are defined as emission reductions in relationship to a reference year (2021), rather than as nominal standards as was the case in the previous Regulations. This is the result of a change in how car emissions are calculated. Owing to large-scale discrepancies between estimated emissions and real-world emissions in the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) test procedure, the EU decided to use a new, more representative Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP)36. As the WLTP equivalent of NEDC emission values will most likely be much higher, emission standards in reference to baseline WLTP emission values are meant to ease the transition for carmakers and to avoid drastic emission reductions for them. Consequently, at the time of policy formulation, the precise 2025 and 2030 standards were unknown. The EEA3 has continued to use the NEDC values to estimate the standards, resulting in 80.8 g CO2/km by 2025 and 59.4 g CO2/km by 20303. Provisional data from the EEA43 suggests that the WLTP equivalent of the NEDC values would be 114.7 g CO2/km. This would significantly increase the nominal emissions allowed under the standards to 97.5 g CO2/km by 2025 and 71.7 g CO2/km by 2030. As the EEA3 has continued to use the 95 g CO2/km in its reports and for the sake of comparability over time, I will use the NEDC values in my analysis, keeping in mind that the standards will most likely be higher.

As such, the 80.8 g CO2/km by 2025 and 59.4 g CO2/km by 2030 standards close the gap between the baseline and ideal scenarios by around half to three quarters (see Fig. 2). To be in line with the economy-wide emission reduction target of 40% by 2030 of the 2030 Framework, the ICCT44 estimated that the EU needed to set emission standards of 65 g CO2/km by 2025 and 40 g CO2/km by 2030. Furthermore, using the same approach as for the 2009 Car Regulation to derive the ideal standards from the economy-wide emission reduction pathway, the standards would need to be around 70 g CO2/km by 2025 and between 50 g CO2/km by 2030. Consequently, as the baseline remained at 95 g CO2/km, the 2025 standard closed the gap with the ideal scenario by around 46–56%, and the 2030 standard closed it by around 65–90%.

While the standards are still inconsistent with the economy-wide target, the 2019 Regulation also limited flexibilities, improving the legislation slightly on that front42. There are no phase-ins of the targets, and the super-credit system is replaced by the introduction of benchmark shares of ZLEV to encourage their uptake. These benchmarks could strengthen the emission reductions rather than weaken them. However, if a carmaker exceeds the benchmark of a 15% share by 2025, their emission reduction target will be weakened.

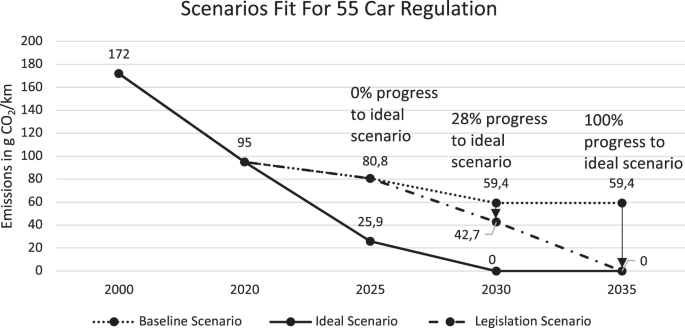

Lastly, as part of the EGD and the Fit For 55 Package, the EU revised the 2019 Regulation to align it with the objectives of net-zero by 2050 and 55% emission reduction by 2030. The provisional agreement on the revised Regulation between the Council and the Parliament—before formal adoption—included the standards of 55% emission reduction by 2030 compared to 2021, and 100% emission reduction by 203545. Both the baseline and ideal scenario have shifted. The baseline followed the 2019 Car Regulation targets, and the ideal scenario is derived from the updated 55% economy-wide emission reduction target. This resulted in ideal standards of around 25 g CO2/km by 2025 and 0 g CO2/km by 2030, an earlier phase-out date than required for the Regulation to be in line with the net-zero by 2050 objective (see Fig. 3). Therefore, because the 2025 target was not revised, its shortsightedness greatly increased considering the more ambitious economy-wide target. Additionally, the revised 2030 target only made limited additional efforts to close the gap to the updated economy-wide 2030 target. Some Member States, including France, Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands, have announced an earlier phase-out date of 2030, that would increase the car sector’s contribution to the economy-wide 2030 target46. Assessing the 2035 standard, the zero-emission standard is in line with the economy-wide net-zero by 2050 objective. As such, while the 2035 standard can be considered farsighted, a case could be made for a faster decarbonization of the car sector.

Concerning flexibilities, the Regulation maintained the benchmark system of the 2019 Regulation that gives carmakers lower targets if they reach a certain share of ZLEV between 2025 and 202945. However, the 2025 benchmark is raised to a 25% share of ZLEV.

Overall, it seems that the inconsistency and hence shortsightedness of the standards has increased over time, considering the most likely more inconsistent standards of the 2019 and Fit For 55 Regulations due to their use of a higher baseline scenario than the one used in the analysis. This suggests that the car sector has not been able to keep up with the increased economy-wide ambition of the EU. Interestingly, in each instance, the medium-term standards of the Regulations—respectively, for 2020, 2030, and 2035—were more consistent with the economy-wide targets than the nearer-term ones for 2012, 2025, and 2030. This could be another indication of shortsightedness in which near-term costs are transferred to the future. Furthermore, each Regulation contained flexibilities for carmakers to delay or weaken their emission reductions. Even though the later Regulations attempted to limit the flexibilities somewhat, they still impacted the realized emission reductions, and increased the standards’ inconsistency.

Stringency

Most of the stringency provisions seem to have remained stable over time. All Regulations are enshrined in law, and manufacturers have to pay a fine if they exceed their targets35,38,42,45. In the 2009 Regulation, the amount of the fine depended on the size of the exceedance until 2018, afterwards the fine was set at €95 g CO2/km for each new car35. Additionally, the Regulations contain substantive and procedural obligations without any significant changes between them. The standards remain legally binding, and the reporting and monitoring obligations remain largely the same.

Nevertheless, the 2019 Regulation made two important changes: one that could weaken and one that could strengthen the stringency of the legislation42. First, while the 2012 and 2020 emission standards of the 2009 Regulation are well defined, the 2025 and 2030 standards of the 2019 Regulation are less precise due to the uncertainty surrounding the reference year values. The imprecision of the standards could offer room for carmakers to weaken them47. It could give them an incentive to have high test emission values in 2021 as this will result in higher, and thus weaker, 2025 and 2030 emission standards.

Second, a different test procedure that is less easily manipulable will be used to calculate car models’ emissions from 2021 onwards42. Already in 2009, first indications emerged that the previous test procedure (NECD) might underestimate real-world emissions due to the manipulation of loopholes by manufacturers48. Further studies showed a growing gap between the test emission values of the NEDC procedure and real-world emissions of up to 30–40%23,39. The discrepancy between test and real-world emissions led to a significant overestimation of emission reductions. As such, it greatly reduced the stringency of the 2009 and 2014 Regulations and made elements such as the fines symbolic. To close the emission gap, a new, less manipulable, test procedure (WLTP) will be used from 2021 onwards as mandated by the 2019 Regulation42. Nevertheless, despite its higher accuracy, a gap between test emission values and real-world emission values will most likely persist—albeit it will be a smaller one40. The 2019 Regulation also opened the door for the use of portable emission measurement systems (PEMS) that test emissions while driving on the road rather than in a laboratory. This could further close the emissions gap. However, if PEMS were to be used, it would only be after 2030.

The Fit For 55 Regulation maintained these changes. Its standards were imprecise because of the 2021 baseline, and the reported emissions would be more accurate due to the WLTP approach45. Additionally, the Regulation included provisions for a close monitoring of the gap between real-world and test emission values with the objective of closing the gap from 2030 onwards.

Overall, the stringency provisions of the 2009 and 2014 Regulations can be considered mostly symbolic due to an unrepresentative test procedure that overestimated cars’ emission reductions. While the transition to the WLTP in the 2019 and Fit For 55 Regulations alleviated this issue, the targets themselves were less precise and the gap between test and real-world emissions persisted. It hence remains to be seen whether the changes will be sufficient to create more stringent legislation.

Adaptability

The adaptability of the Regulations seems to have increased incrementally over time, mainly due to the expansion of the elements included in the scheduled reviews and revisions35,38,42,45.

The scheduled reviews did not contain a revision of the standards included in the legislation until the 2019 Regulation42,45. Previously, the review focused either on non-essential elements and the way to reach the standards (2009 Regulation), or on how future standards and legislation can be improved (2014 Regulation). In the absence of a revision of the set standards, the direction of the review was not specified beyond vague declarations on “realistic and achievable” standards38. Once the Regulations’ standards were included in the review, the direction also became clearer, as demonstrated by references to the Paris Agreement and net-zero emissions in the 2019 and Fit For 55 Regulations. Nevertheless, the Regulations did not specify the scientific insights the reviews should be based on, suggesting a gap in the legislations’ adaptability. Additionally, the reviews and revisions seemed to be planned ad hoc rather than following a structured review cycle. The Fit For 55 Regulation mitigated this as it included two-year progress reports and reviews.

Long-term thinking

The long-term thinking of the legislation can be considered insufficient and has only incrementally improved over time35,38,42,45. The 2009 Regulation included neither a long-term objective for the emission reductions of cars, nor a reduction pathway35. In 2011, the EU formulated its first strategy for the decarbonization of the transport sector49. However, the strategy did not have a specific target for car emissions, and its objective of a 60% transport emission reduction by 2050 compared to 1990 was significantly lower than the economy-wide emission reduction objective of 80–95% reduction by 2050. Because of the strategy’s lack of a long-term objective for cars, the long-term thinking of the 2014 Regulation that referred to it can still be considered insufficient38. The 2019 Regulation contained slightly more long-term thinking, as it mentioned the Paris Agreement’s objective, the IPCC, and the EU’s own economy-wide long-term objective for 205042. However, despite clarifying the importance of further reducing CO2 emissions from cars beyond 2030, the Regulation did not include a precise long-term objective for cars nor a mitigation pathway. Lastly, the long term was somewhat more present in the Fit For 55 Regulation as it also mentioned the more farsighted objective of 90% reduction of transport emissions by 2050, and the necessity of economy-wide negative emissions after 205045.

A close reading of the positions of the Commission, Parliament, and Council showed that there was no clear push from the institutions towards more long-term thinking in their positions on the 2009 and 2014 Regulations50,51,52,53,54,55. The Commission and the Parliament did not mention the long term in their positions on the 2009 Regulation, and only did so in relation to the 2014 Regulation. Discussion of the long term was completely absent from the Council’s positions during this time. Concerning the 2019 Regulation, the institutions referred more strongly to the EU’s long-term transport objective of 60% emission reduction by 205056,57,58. Additionally, long-term thinking featured more heavily in the Parliament’s position on the Fit For 55 Regulation59,60,61. The mentions of negative emissions after 2050 and of the objective of 90% reduction for the transport sector by 2050 seem to originate from its position.

As such, even though long-term thinking has incrementally become more present in the legislation and in the institutions’ positions, the analyzed documents provide no evidence for adequate long-term thinking. Most importantly, a clear long-term car emission reduction objective and a mitigation pathway toward it, remained absent throughout the different legislative processes. Only the Parliament suggested a more concrete net-zero objective in the 2019 process. This suggests that the standards may have an ad hoc quality, rather than being part of a structured pathway to reduce the car sector’s emissions.