Germany may have the world’s third-largest economy and a hot stock market, but its prospects are not looking good.

In a nutshell

- Germany underperforming amid industrial stagnation, labor shortages and high energy costs

- Subsidies are not helping to rescue the economy

- This trend will continue until Baby Boomers retire, creating an urgent need for difficult reforms

Germany is the biggest economy in the European Union. It accounts for about a quarter of the bloc’s gross domestic product (GDP) and since 2023 it ranks as the third-largest economy in the world, surpassed only by the United States and China. In early spring 2024, its headline stock index, the DAX, was hovering around all-time highs.

And yet, its economic prospects are not looking good.

Reports of Germany’s dire situation are piling up, and members of its federal government are expressing pessimism – sometimes, even self-criticism. That alone should set alarm bells ringing. Whenever the political leadership of a country engages in self-criticism, even if only partial and dishonest, it should be taken as a sign of serious troubles; especially if the given country is the economic engine of an entire continent. There is no more denying that “Germany’s fat years are over,” as Professor Gunther Schnabl has put it in his new book on the German predicament.

In recent years, Germany has underperformed compared to the EU average, even while the bloc has experienced a period of general distress and decline. Rising German stock prices are a sign of expectations for renewed monetary easing and a devaluation of the euro on the international foreign exchange markets. They certainly do not stem from real productivity gains in recent years nor from improved economic conditions in the overall economy. Macroeconomic indicators across the board show negative trends, from GDP and industrial production to competitiveness, migration numbers and the cost of living.

The administration of Chancellor Olaf Scholz faces the most daunting economic challenges since German reunification. These hurdles can only be overcome if the administration adjusts its political direction. In many cases the government would have to completely reverse certain measures to return to a robust economic growth path. Whether the administration has the political will to do that is doubtful, but the hard facts could persuade them to give in, if only out of political self-interest.

Industrial production and real economic growth

Germany’s economic performance has disappointed for a long time. Since the introduction of the euro in January 1999, Germany’s real GDP growth has averaged less than 1.2 percent per year. Across the EU, the average annual growth rate has barely surpassed 1.5 percent.

It is not surprising that Germany’s overall growth rate comes in below the European average. This aligns with a general pattern around the world. When economies of different strengths grow together and integrate, the weaker regions’ overall growth tends to outpace other areas, due to the catch-up effect of economic convergence. Nevertheless, overall growth in Europe has been rather sluggish and is trending downward.

Industry is still considered the heart of the German economy. The gross value added by industry (minus construction) as a percentage of GDP, has averaged 22.6 percent since 2014. It therefore accounts for a fifth of Germany’s economic output. This is well above the EU average of 18.1 percent and far above the figure for the next largest European economy, France, at just 12.4 percent. In the early 1980s, industry still accounted for around a fifth of total economic output in France too. But since then, the French economy has largely de-industrialized. Germany could follow this trend faster than expected. The reason for this is not least the misguided economic policy of recent years.

Read more on the economic challenges of our time

Increases in energy prices have had a particularly negative impact on industry, owing to its high energy requirements. It is often argued that Germany became particularly dependent on gas and oil supplies from Russia as a result of its decision to phase out nuclear power in 2011. However, this does not mean that the rise in energy prices in Germany has been greater than in other European countries. On integrated markets like those in Europe, energy is always sold where it is most expensive, which is why disproportionate price increases in certain regions tend to be prevented.

In other words, if energy prices rise in one country of the EU’s common market, they rise everywhere. In Germany, such prices have risen by 53.2 percent since February 2021, in line with the 53.5 percent average increase across the EU. The German economy has therefore not been hit harder than other European countries in this respect; it just suffers more from it, because of its relatively high share of industrial production in overall GDP.

The situation is even worse if we focus on industrial production specifically, and its relative performance in Germany. Here, the decline is more pronounced compared with the rest of the EU.

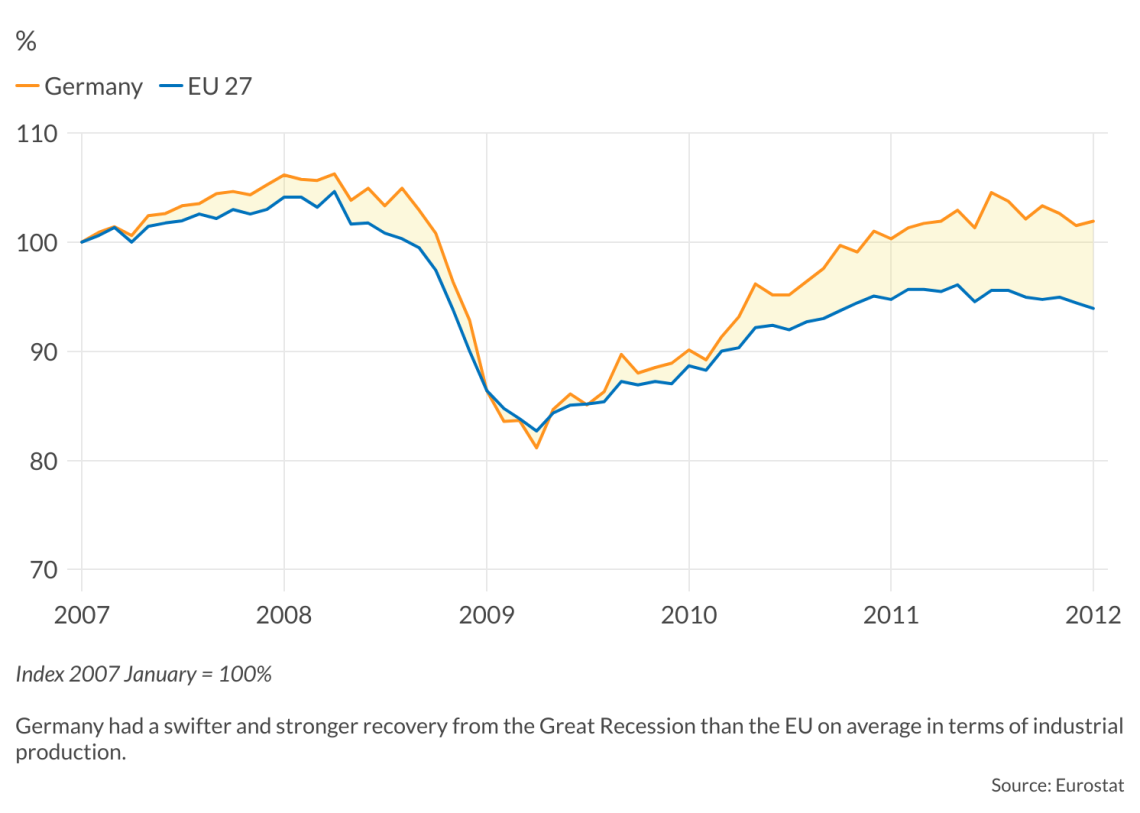

This was not the case just over a decade ago. During the disruption caused by the financial crisis of 2008, for example, industrial production in Germany and the EU fell by around 25 percent. However, it recovered much faster in Germany than in other EU countries. From its low point in April 2009, it rose until, in January 2012, it was well above the level of January 2007, with an average annual growth rate of 8.6 percent. The EU average annual growth rate over the same recovery period was only 4.7 percent and industrial production did not return to pre-crisis levels. German industry therefore came out of the Great Recession surprisingly well, while the rest of Europe lagged behind.

Facts & figures

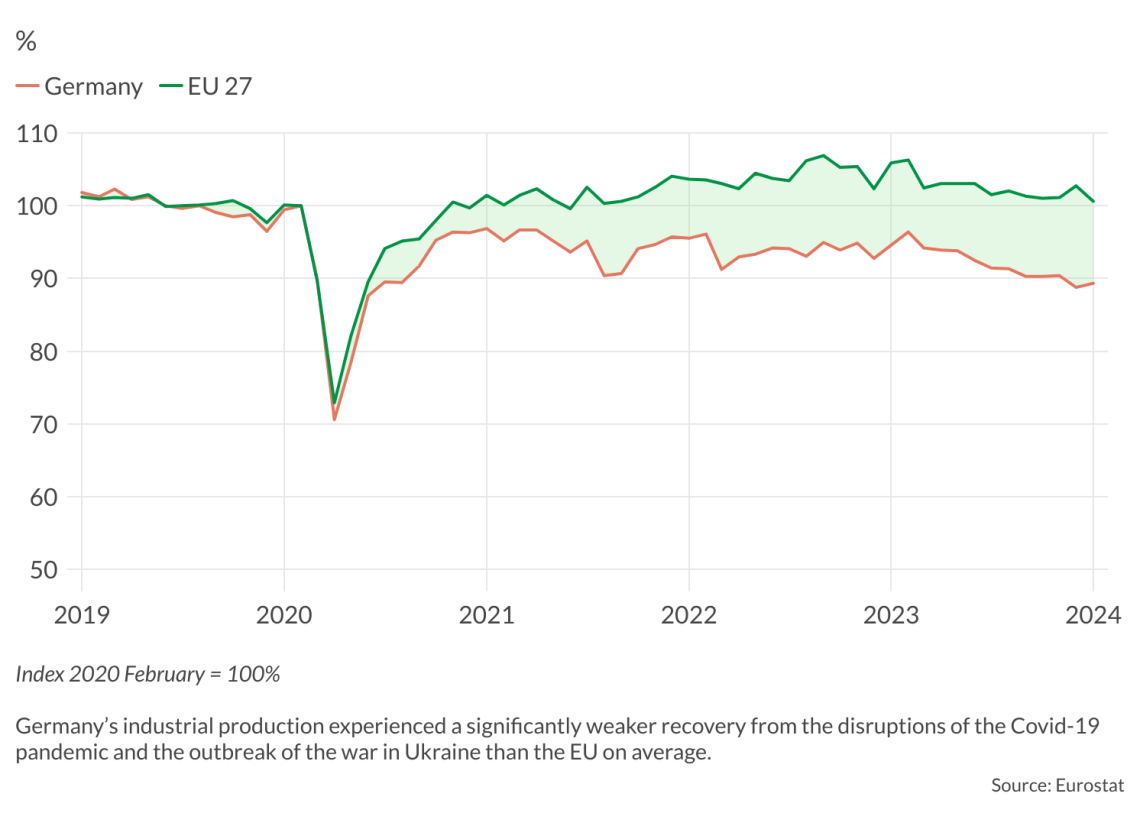

The tides have since turned. The slump that occurred after the Covid-19 pandemic was even more drastic overall than the 2008 financial crisis. In 2020, industrial production collapsed by around 30 percent in both Germany and the EU as a whole. Since that time, whereas Europe on average has been able to return to above pre-crisis levels, Germany has not.

Facts & figures

Germany is continuing a negative trend in industrial production that had already begun before the disruption of Covid-19. The German government’s climate measures in particular, such as the gradual phasing out of the combustion engine and the switch to electromobility, are having an impact. The German automotive industry has not yet been able to compensate for these losses.

Record levels of subsidies do not seem to be solving the problem. Compared to the average value between 1999 and 2019, annual subsidies for the German economy have more than doubled. In the peak year of 2021, they more than tripled. German industry is thus becoming a pawn in a large-scale project of central planning. It loses competitiveness as businesses are guided by subsidies into ventures where they otherwise lack a comparative advantage over international competitors.

Labor markets and productivity

At the end of the 1990s when the Schroeder government took office, Germany suffered from high unemployment. The implemented labor market reforms were a huge success from which the subsequent Merkel administration greatly benefited. Today, the main problem when it comes to labor markets is a shortage of skilled workers.

There are two primary reasons for this shortfall. The first is a severe distortion in the way Germany’s demographics are developing. The Baby Boomer generation has started retiring, and fewer younger people are entering the labor market, especially those with professional experience.

Only when inevitable demographic problems strike with full force through the retirement of the entire Baby Boomer generation will there be sufficient political incentives for meaningful reforms.

The second is that, despite Germany having a significant and growing migrant population, the OECD already noted in 2013, prior to the refugee crisis, that the “gap in learning outcomes between immigrant and non-immigrant students remains higher in Germany than in many other OECD countries.” This is an indicator that Germany has had more low-skill immigrants than other countries.

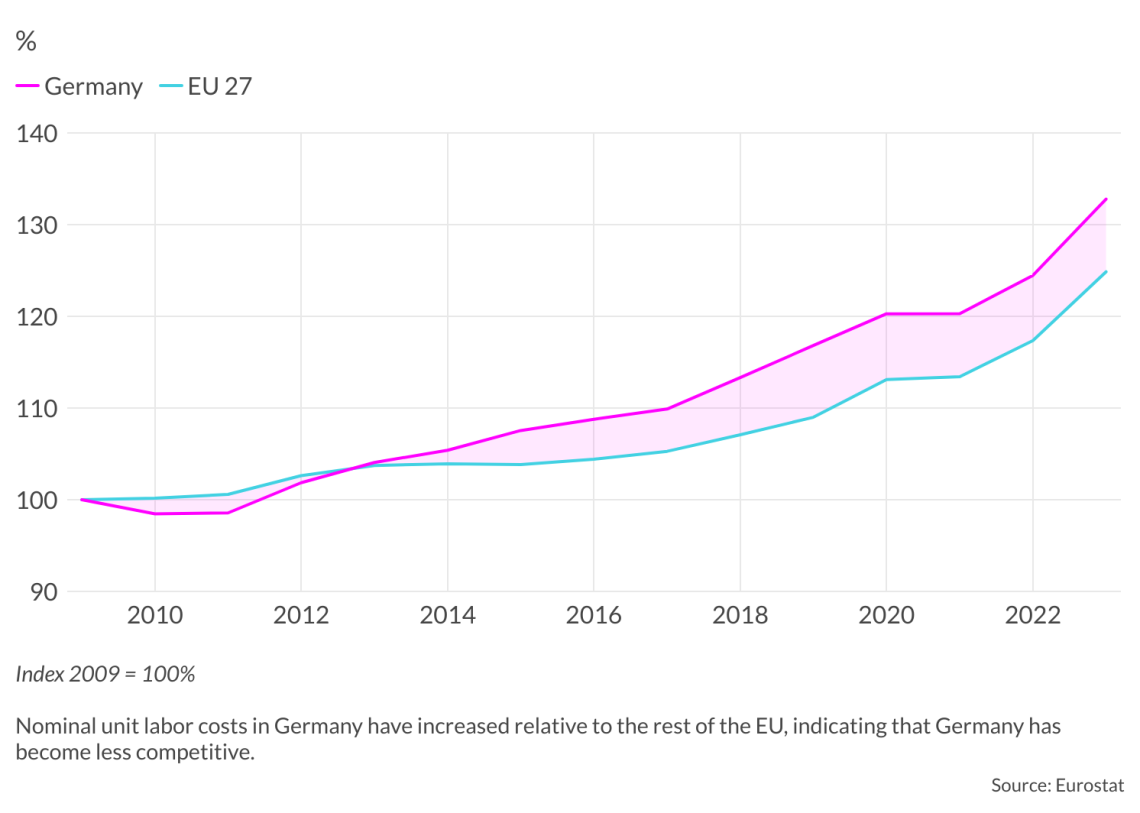

Both demographic pressure and low-skill immigration are causing the shortage of skilled workers. This leads to declining productivity overall, as indicated by rising unit labor costs.

In Germany, nominal unit labor costs have increased on average by half a percentage point since the Great Recession compared to the EU average. These developments gradually make Germany a less attractive country for corporate investment.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

There are three possible scenarios, with the most likely outcome being a continuation of current trends with the potential for some improvement in coming years – if politicians can find the will for change.

Least likely: Complete abandonment of the market economy in favor of outright central planning

Advocacy for more fiscal redistribution, government regulation, radical environmental protection and far-reaching social and cultural change are on the rise, especially among younger generations. All these forces push toward increased political control over investments in the economy and ultimately outright central planning of production. This scenario is scary for everyone who appreciates classical liberal arguments against government control of the economy.

This scenario, though, is not very likely. It is true that short-term social problems can be solved through more redistribution, but the already declining overall standard of living will fall even more in the medium term. And nothing is stronger in changing political positions than a declining living standard.

Quite unlikely: A new Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle

The most optimistic though still unlikely scenario in the near future involves economic policy reforms for long-term growth and productivity gains. This requires the reduction of bureaucratic red tape, as well as the reduction of taxes, subsidies and market regulations to unleash the full potential of an unhampered price system and the signals it provides for the efficient allocation of labor and resources.

In this scenario, Germany will need to attract more highly skilled workers by providing better conditions for them in terms of their overall living standard. This can be accomplished through a generally lower tax burden and a higher net remuneration. Germany will also have to prevent ongoing migration into the welfare state, which is becoming an ever-greater burden. It is doubtful whether there is the necessary political will for these far-reaching reforms.

The country’s first spectacular economic recovery, the Miracle on the Rhine after World War II, came when Germany was in ruins. Fortunately, we are still a long way from that. Even if many citizens are clearly feeling the effects of the recent downturn, it could be that the problems have not yet been sufficiently recognized by political leaders. Some steps in the above direction might be undertaken, but the whole package for a new Wirtschaftswunder seems unlikely, at least in the near future.

Most likely: Continued decline under the guise of progress

It seems very likely that Germany will continue on the current trajectory for at least a few more years. The ideological and political commitment to environmental regulations and social reform, including more economic equality, is relatively strong and often fueled by opportunism on the part of lobby groups and big corporations.

Only when inevitable demographic problems strike with full force through the retirement of the entire Baby Boomer generation will there be sufficient political incentives for meaningful reforms.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.