This week MEPs vote on the revised EU economic-governance framework. The stakes could not be higher.

Progressives gearing up for the next term have a long list of critical issues to tackle: transforming the European Green Deal into a truly green and social deal, pivoting the European Union from ‘green growth’ to post-growth economics, overhauling the narrow approach to just transition, adapting welfare states to climate risks and refocusing the industrial agenda on quality jobs and environmental standards.

Yet the hard truth is that if we do not stand firm against the new fiscal rules, all these proposals will go out of the window. Our manifestos will be toothless without the ability to invest massively in a just transition to climate neutrality. Unless progressives snap out of their slumber and reject this austerity pact by casting a ‘no’ vote on Tuesday in the European Parliament, we shall be complicit in our own downfall.

Widespread criticism

The ‘old’ fiscal rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) faced widespread criticism for their pursuit of arbitrary numerical targets without any economic justification: the infamous ratios to gross domestic product of budget deficits (3 per cent) and public debt (60 per cent). These rules, which imposed a fiscal straitjacket on national budgets, have been counterproductive—promoting short-term thinking, neglectful of spending quality and unenforceable (due to their reliance on unobservable variables prone to ex post revisions). Since the European Commission initiated its review of the SGP in 2020, numerous reforms have been advocated to safeguard public investment in social welfare and facilitate the ecological transition.

Amid recent social, ecological and geopolitical crises, there was optimism that the EU would finally take decisive action to revamp its economic governance. The pandemic prompted a suspension of the SGP in 2020, allowing for increased deficit spending to safeguard citizens. This was extended until 2024 in response to surging energy prices across the EU. These four years underscored the essential role of government intervention and emphasised the importance of public services, as well as the invaluable contributions of healthcare and education workers.

The release of revised economic-governance guidelines by the commission in 2022 fell short of expectations. While acknowledging some criticisms of the outdated rules, the proposal failed adequately to prioritise public investments. It could, nonetheless, have offered a basis for negotiations.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

Since then, led by the German finance minister, Christian Lindner, and supported by the so-called ‘frugal’ countries, the old guard has fought back and the situation has actually worsened. After two years of debate, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached an agreement on the legislative package, backed in the parliament by the conservative European People’s Party and the liberal Renew groups, with the perplexing complicity of the Socialists and Democrats. The new economic-governance framework would sustain arbitrary and complex rules blindly prioritising debt and deficit reduction over key EU policy objectives, such as the green deal and social cohesion.

Debt fundamentalism

Each member state’s fiscal plan would be based on a single net-expenditure reference trajectory, dictating the required annual reduction in government spending. The commission’s debt sustainability analysis (DSA) would set the variables and assumptions under which any trajectory was deemed plausible, and so the speed of medium-term fiscal consolidation. Debt sustainability is imperative to prevent sovereign default, market panic and reliance on bailouts. But the reform would enforce systematic debt reduction below arbitrary thresholds.

The commission’s methodology is overly focused on debt-to-GDP dynamics and fails adequately to integrate financial-market indicators such as debt affordability (interest rates have steadily decreased since the 1990s) or debt structure (EU debt is primarily held domestically). Crucially, a reliable analysis should take into account the fiscal consequences of climate inaction, which require an increase in green expenditure to finance rapid adaptation.

The DSA methodology is the black box within the governance framework: the outcome depends on the assumptions used in forecasting (potential) growth, inflation, interest rates, unemployment and so on—on which small changes can have massive effects. It is based on contentious macroeconomic and statistical models and lacks consensus among economists, as revealed in the expert hearing of the parliament’s economic-affairs committee last September.

EU leaders are looking at economic reality through the eyes of an ideologically blinkered accountant. Meeting the urgent challenges we face—climate change, economic disparities, war on our doorstep—requires more, not less, public investment. Their debt fundamentalism will lead to the brutal reinstatement of harsh austerity.

Massive budget cuts

The new economic-governance framework will force most member states to implement massive budget cuts. Debts will have to be reduced annually by 1 per cent of GDP for high-debt countries (above 90 per cent debt/GDP) and 0.5 per cent for medium-debt countries (60-90 per cent). The 3 per cent deficit limit in the treaties is supplemented by the deficit-resilience safeguard pushed for by Germany, meaning countries will have to continue reducing their structural deficits until these are below 1.5 per cent of GDP.

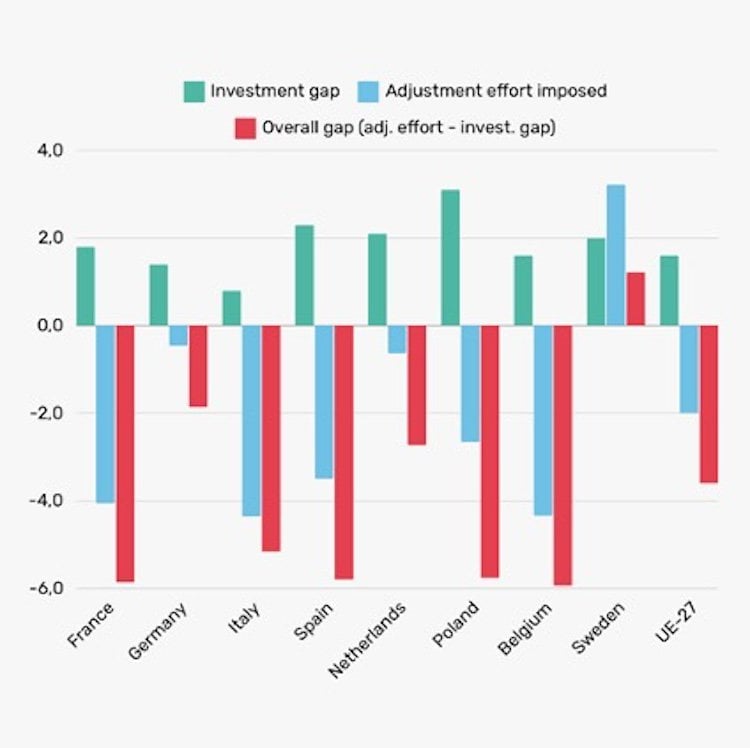

The stringent budget cuts foreseen are estimated to total about €100 billion in the first year of application alone. In the coming four years, countries such as France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands are anticipated to undertake the biggest cuts, ranging from €6 to €26 billion annually. Last week the independent fiscal institution in France strongly criticised the government’s trajectory to come within a 3 per cent deficit, claiming it lacked credibility.

The new framework will impose a significant constraint on governments in the coming decades, precisely when the EU must confront exceptionally high investment requirements. A study commissioned by the Greens/EFA group in the parliament from the Institut Rousseau calculates the concrete investment needs for the green transition, sector-by-sector, at 2.5 per cent of EU GDP annually to reach the union’s net-zero objective by 2050.

This requires a combination of private and public investment, public funds playing a crucial multiplier role. While the demand for increased public investment may vary across countries, a conservative estimate suggests an average annual requirement of approximately 1.6 per cent of EU GDP. In other words, public expenditure needs roughly to double from €250 to €510 billion per year. Remarkably, this substantial investment is still less than what the EU has spent on Covid-19 recovery or fossil-fuel subsidies, underscoring its feasibility.

Yet implementation of the new fiscal rules would leave governments unable to meet this objective. Adding the required adjustment efforts to the shortfall in green investment would leave a gap amounting to nearly 4 per cent of EU27 GDP (Figure 1).

Figure 1: investment gap, adjustment effort and overall gap (percentage points GDP)

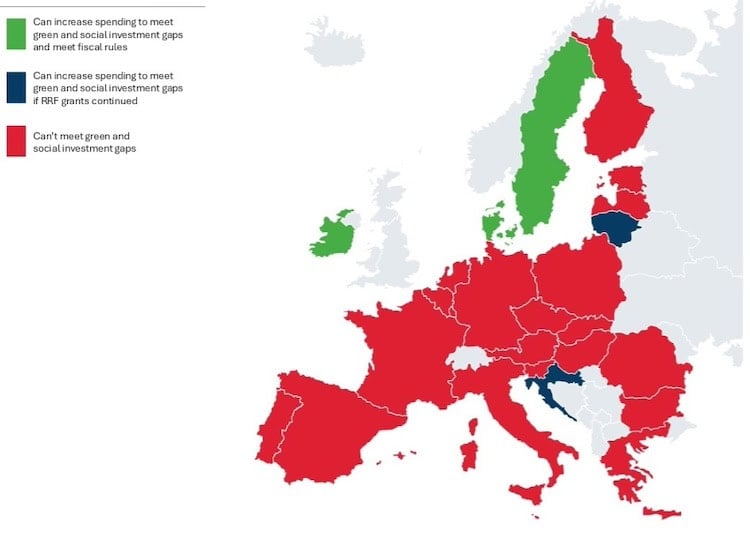

Furthermore, a study commissioned by the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) reveals that the envisaged rules will hinder most EU states from achieving their investment targets for social infrastructure. The commission estimates that the EU needs to invest €192 billion annually in health and long-term care, affordable housing and education. But under the proposed fiscal rules, 18 member states, including Germany and France, will fall short.

When examining both social and green investment needs, the study indicates that only three member states would retain the fiscal capacity to meet the EU’s investment targets. Even were there to be an extension of the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF), only five member states could achieve both social and ecological investment targets while operating within the constraints of these rules (Figure 2).

Figure 2: map of social and green investment gaps if fiscal rules applied and RRF grants continued

The exclusion of national co-financing of EU-funded programmes from net-expenditure calculations is touted by the S&Ds as a victory for investment-friendly policies. Yet all 27 member states will only be able collectively to exclude around €29 billion per year, equivalent to the co-financing for the cohesion and agricultural funds. Furthermore, the design of this exception can lead to unintended consequences in the medium term. Co-financing is not excluded from debts and deficit calculations. Heavy spending on co-financing could thus inflate a member state’s debt/GDP ratio, potentially leading to more cuts in other areas of expenditure.

Undermining trust

If the economic-governance reform package is approved, member states will have to forgo investments: any trade-off between cuts in current expenditure and investment usually means investment is cancelled or postponed, as seen throughout Europe after the financial crisis. Member states committed to the required investment in the ecological transition will have to make cuts elsewhere, typically in major social and health expenditures. But forcing governments to choose between social and green expenditure risks sparking social unrest and undermining trust in institutions once more—potentially bolstering support for far-right ideologies.

Dsregarding the rules to make the investments will meanwhile carry higher political costs than with the old framework. Widespread violations could provide arguments for austerity advocates to obstruct the introduction of EU funding schemes.

New taxes—on wealth, inheritance and pollution—could help bridge the investment gap in the fairest way. A wealth tax, for instance, could yield up to €273 billion annually if accompanied by measures to combat avoidance. But while a significant portion of public expenditure can be financed through increased and more progressive taxes, that may not be sufficient. Nor can we be confident to have the political majority in the next EU mandate to back tax increases on the super-rich to fund the indispensable and urgent investments. Relying, at least partially, on debt financing to meet our objectives is unavoidable.

Another major avenue would be to establish a European investment capacity, empowered to borrow jointly at EU level to fund shared policy priorities. This would alleviate pressure on national budgets, offer cheaper borrowing rates and allow for EU oversight to ensure funds were allocated to EU priorities. A common European central capacity of at least 1 per cent of EU GDP would be key to address the investment gap. Yet much of the bulk of green and social investment effort will remain in national hands.

Painted into a corner

In short, with these short-sighted, ideological rules, EU leaders have painted themselves into a corner. Failing to finance the transition will lead to Europe falling behind the United States and China on net-zero technologies and manufacturing, putting our workers in precarious conditions, making our societies poorer and at the same time putting at risk our ability to keep our existing public debt sustainable.

Rules are necessary, undoubtedly. We need a revamped economic-governance framework to provide the means to address existential threats and reach common EU objectives. This should focus on the quality of public spending and protect public investments. It would contribute both to debt sustainability and to the ability of the EU to tackle current and future challenges.

To establish effective rules, however, renegotiation is imperative. And for that, the only sensible course of action is an unequivocal rejection of austerity. It is crucial that all progressive MEPs cast a resounding ‘no’ vote to austerity in Strasbourg. A victory would empower our collective efforts to push for our social-ecological agenda for the next term.