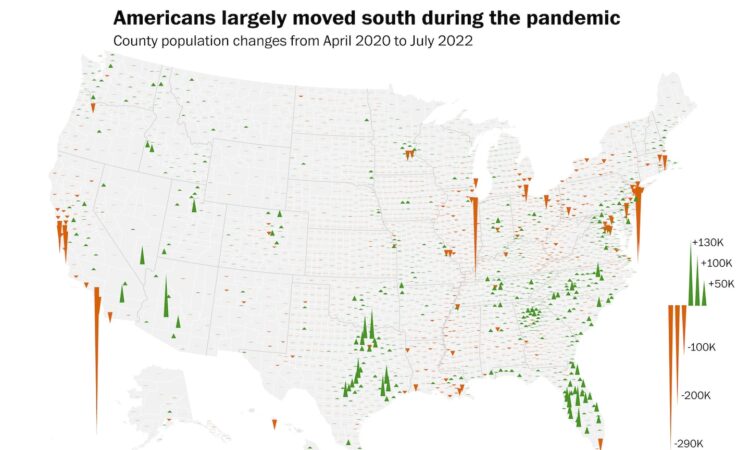

But the pandemic forced a major rethink of this “bigger is better” concept. Suddenly, living so close together had downsides, and many people could do their jobs remotely. Now, megacities aren’t dead, but they’ve lost some of their luster.

Americans largely moved south

during the pandemic

County population changes

from April 2020 to July 2022

Los Angeles County lost the most population;

Maricopa County in Arizona, where Phoenix is

located, gained the most.

Americans largely moved south

during the pandemic

County population changes from

April 2020 to July 2022

Los Angeles County lost the most population;

Maricopa County in Arizona, where Phoenix is

located, gained the most.

Americans largely moved south during the pandemic

County population changes from April 2020 to July 2022

Cook County,

Illinois (Chicago)

Kings and

Queens County,

New York

Los Angeles County lost the most population;

Maricopa County in Arizona, where Phoenix is

located, gained the most.

Americans largely moved south during the pandemic

County population changes from April 2020 to July 2022

Cook County,

Illinois (Chicago)

Kings County

and Queens County,

New York

Los Angeles County lost the most population;

Maricopa County in Arizona, where Phoenix

is located, gained the most.

Millions of Americans moved over the past few years. The relocators have been overwhelmingly people with college degrees, especially millennials with young kids, many of whom wanted more space for less money. There was a mass relocation from expensive coastal cities — especially New York and San Francisco — to lower-cost places such as Phoenix, San Antonio, Jacksonville and Charlotte.

Conventional wisdom would say this big relocation should have been terrible for America. So much talent — and money — left “superstar cities” for what the real estate world calls “second tier” cities, or small vacation towns at the beach or in the mountains. According to traditional economic thinking, this should bring years of lower growth and productivity, because highly educated workers and capital are spread too thin. But there’s reason to believe the conventional view is wrong.

First, remote workers are still connected to New York, San Francisco and other big cities. Video technology is now good enough — and accepted enough — to enable virtual brainstorming and networking. People don’t need to live in the same Zip code to trade ideas and benefit from being near each other.

Second, America’s largest cities don’t have enough housing. This is a crisis. And it’s why, even before the pandemic, people were migrating to lower-cost locales, especially in the South. Millennials’ moves during the pandemic helped alleviate some of the urban housing crunch. The moves also freed up a lot of money. People who relocated can now use some of the money they were spending on high rent and costly mortgages to start businesses, invest or consume more.

Third, many people relocated to what I would call rising-star cities. Phoenix (population 1.6 million) and San Antonio (1.5 million) were already among America’s 10 biggest cities. Jacksonville and Charlotte are both close to having 1 million residents. These places have much the same creative and energetic vibes that megacities have. There is no exact threshold of people or money that a city reaches and then magically starts providing that extra productivity boost. But it’s getting hard to argue that someone living in Brooklyn is more productive and valuable to the U.S. economy than someone living in Charlotte.

What’s more, rising government and private investment in semiconductors and green energy is injecting more capital to places such as Phoenix and Austin. It’s a mistake to ask, “What city will replace Silicon Valley?” The ideal is to spark niche innovation across the country.

“We’re seeing an entrepreneurship boom in the South and Sun Belt,” said economist Benjamin Glasner of the Economic Innovation Group. “People are moving to new places and noticing opportunities.”

Americans are also generally happier with their jobs than they’ve been in decades. Many used the Great Reassessment to change careers and find higher-paying jobs that better suit their skills and interests. Those who moved or work remotely at least some of the time generally report better work-life balance, because they spend less time commuting. All of this can help boost productivity.

The pandemic changed society in ways we are only beginning to recognize and understand. It caused many people to take risks in pursuit of more fulfilling lives. Americans are opening businesses at rates not seen in decades. Growth has been surprisingly strong despite high interest rates. And there are early signs of a productivity boom similar to that of the 1990s. Productivity could be getting a boost from artificial intelligence, but don’t discount the impact of happier workers and, possibly, the big relocation.

This is not to say everything is rosy. Some people now regret their cross-country moves. And the housing crunches and hefty rent hikes that used to be a problem mainly in New York City and San Francisco have become commonplace across the nation, especially in Florida.

But the U.S. economy’s secret power has long been adaptability. This nation has emerged from crises stronger than many other places because American workers and companies shift faster. Now it turns out that remote work and the big relocation are extending megacity benefits around the country. Imagine an era of rising productivity — and better lifestyles — in many more locales.