While Greece is known as the birthplace of democracy, more recently, it has also come to be known as a kind of policy laboratory for the European Union. No other country has suffered so directly from the austerity measures prescribed by Brussels. At the same time, it is the country – within the Nato group – that has allocated the highest percentage of its GDP to military spending, reaching 3.5 per cent this year – even more than the United States. In line with the programme of the formations that won the European elections at the beginning of June, this very approach – greater austerity and high military spending – will mark the budgets for the coming years. This veritable squaring of the circle can only mean significant cuts in social spending.

Increased military spending by European countries is a long-standing request of the White House, and one that Donald Trump raised to the level of a demand. Washington wants to see the defence budgets of all Nato members reach at least 2 per cent of their GDP. It was not, however, until Vladimir Putin decided to launch the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that the idea gained traction in virtually all European capitals, including Brussels. Most EU governments have committed to reaching this threshold over the next few years, which will involve an additional outlay of around €150 billion a year, and the Commission and the European Central Bank are even considering the possibility of issuing Eurobonds to finance the purchase or manufacture of weaponry, an idea considered off-limits until a couple of years ago.

The increase in military spending, especially to pay for arms for Ukraine, is already a reality, and the European Commission itself has spent more than €5 billion on subsidising the joint procurement of weaponry.

“In 2023, there was a very significant increase in military spending worldwide, but especially in Europe. In Spain, for example, it grew by 24 per cent and in Finland by 36 per cent. If we compare it with 2013, the European countries in Nato are spending 30 per cent more,” says Pere Ortega, a researcher at the Barcelona-based Centre Delàs for Peace Studies, which is critical of measures adopted by the European Commission to promote military spending, such as the VAT exemption for the purchase of armaments or the change in the regulations of the European Investment Bank (EIB) to allow it to finance industrial projects in the military sphere.

Rafael Loss, a security expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) think tank, believes that EU countries need to spend more on defence: “Vladimir Putin’s intent to revise the European security order is pretty clear […]. This is not to say that Russia will send its troops across Nato borders with all certainty, but the risk that its leadership might decide to do so one day is rising.” He also reminds us that the international context is changing: “The strategic outlook of Europe’s main security partner, the United States, is shifting towards the Indo-Pacific.”

Ortega, however, considers the fears whipped up by European leaders about a possible Russian attack to be exaggerated. “Putin would not be so foolish as to invade a Nato country, because he knows it would lead to nuclear war. […] If you want peace, prepare for peace. History shows that the contrary leads to an arms race, which increases the chances of war,” he argues. What Loss and Ortega do agree on is that it does not stand to reason that the armies of European countries have different or even incompatible weaponry, and an effort to unify only makes sense.

The impact of the new fiscal measures

While the specific volume of military spending and the role that Brussels should play in European rearmament are still up in the air, the new budgetary rules that member states will have to abide by as of 2025, and which imply a return to austerity, have already been approved. This means a return to the annual limits of 3 per cent of GDP for public deficits and 60 per cent for public debt, which were only suspended in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some new conditions have nonetheless been introduced to give member states greater flexibility in their pursuit of these deficit targets. Member states that exceed the 3 per cent threshold will, for example, be given more time to consolidate their finances, with the timeframes being extended to four years and, for those with a more serious public debt problem, seven years. “This reform constitutes a fresh start and a return to fiscal responsibility at the same time […]. When you have control of your budget, you do not need austerity,” said Markus Ferber of Germany’s conservative CDU, one of the MEPs most directly involved in negotiating the new budget rules, in a debate on the subject in the European Parliament. The European Commission already started to apply the new rules last week, opening an “excessive deficit” procedure for seven countries: Belgium, France, Italy, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovakia.

“Having sound finances is important because it helps attract investment from the markets. But it is important to strike a balance. An excess of zeal reduces investments in education, infrastructure or health, and this brings another set of problems for the economy,” explains Nick Malkoutzis, head of the Athens-based think tank MacroPolis. Malkoutzis welcomes the introduction of greater flexibility in meeting the criteria but argues that these rules must be accompanied by an EU-wide effort to ensure major investments in key sectors – such as green transition or infrastructure – similar to the Recovery and Resilience Fund, which was approved in the wake of the pandemic and is soon to expire.

For Ludovic Voet, confederal secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), the new fiscal pact is completely misguided. “We made four demands and none of them were respected. They included not imposing a blind formula for debt-consolidation and excluding social and green investments. But the only exception will be military expenditure,” says Voet, who warns of huge cuts in social spending to balance the budgets.

The trade union leader points out that cuts of around €100 billion are forecast to be made in the EU as a whole by 2027, a figure included in a study commissioned by the ETUC on the impact of the new fiscal measures. According to this research, only three countries – Denmark, Sweden and Ireland – will be able to meet both their own commitments on green transition investments and the public spending limit. This is all the more worrying given that, according to the Commission’s own statistics, there is already a €192 billion shortfall in investment in social infrastructure in the EU.

Speaking to Equal Times, Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s former finance minister before resigning in opposition to the structural adjustment programme imposed by Brussels and the IMF, is vehement in his criticism: “This ‘austerity-light’ is a recipe for economic stagnation, which will lead to the rise of the far right. While Europe acts like that, the US and China do have deficits to finance their industrial policy, and the new technological companies and green jobs are theirs. Europe is a technologically underdeveloped continent.”

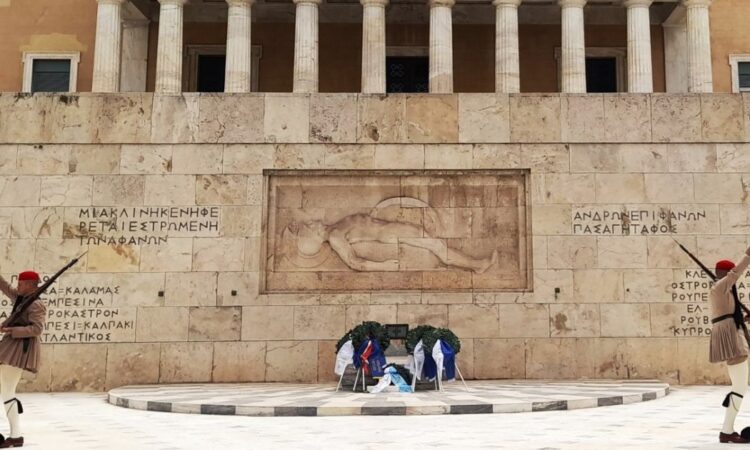

While we wait to see how the new European Commission – which is in the midst of renewal following the European elections of 6 to 9 June – will apply the new financial rules and address the challenges facing the continent, the example provided by the Greek laboratory offers very little hope. After a decade of fiscal adjustment, purchasing power in Greece has plummeted, falling to the bottom of the ladder in the EU, ahead only of Bulgaria, while some of its public services, such as healthcare, have seriously deteriorated, creating a deep sense of disquiet and discontent among the population.

This article has been translated from Spanish.