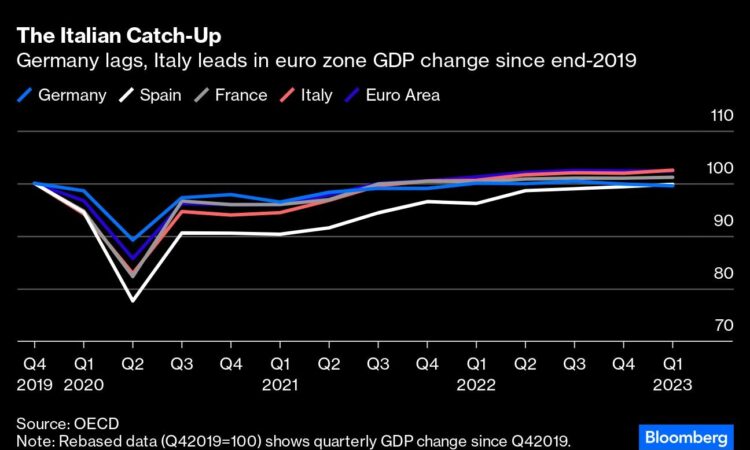

Welcome to Italy’s version of the Mittelstand — competitive, innovative and part of an industrial sector that’s held up better than Germany’s, where a far deeper dependence on Russian gas and Chinese markets dragged its economy into recession. And while not immune to crisis, the Italian economy has staged a remarkable catch-up since Covid-19, outgrowing Germany, France, Spain and the euro average since the end of 2019, according to OECD data.

It’s a recovery that matters hugely to the West as European unity in the face of US-China competition is a major geopolitical fault line. The big question is whether it can avoid being snuffed out by bad political habits and a broader economic slowdown.

Italy’s recent performance obviously clashes with its reputation for basket-case banks, revolving-door governments and a mountain of public debt. Economic growth has been anemic for two decades, as the era of Silvio Berlusconi’s unfulfilled economic promises and corruption gave way to the failures of the anti-establishment Five Star movement and euroskeptics. We are a long way from the 1980s sorpasso when Italy’s nominal gross domestic product eclipsed the UK’s — even Spain’s per-capita GDP exceeded that of Italy in 2017.

Still, the past few years have seen a happy confluence of government support, economic reforms and European Union pandemic spending — of which Italy is the largest recipient, with an estimated potential boost of up to 3.1% of GDP by 2030, according to Eulala Rubio of the Institut Jacques Delors. And the inflation-defying global consumer splash buoying the euro-zone south is set to make 2023 a record year for the tourism industry. Digital nomads in Sicily have mirrored by a post-Brexit boom in wealthy Milan, where real-estate prices have rocketed and financiers have set up shop to take advantage of tax breaks.

The past few years have brought what investors see as political stability. Even last year’s jarring shift rightward from Mario Draghi’s unity government to ultra-conservative Giorgia Meloni has yet to rock the economic boat. While her social agenda treads unprecedented territory, she’s sticking to her predecessor’s budget commitments. The spread between Italy’s bond yield and Germany’s, once a daily indicator of Italian economic stress, has fallen to its lowest in a year. Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio has also fallen but remains high at around 144%.

“For the first time in a while, it feels like Italy has a plan,” according to economist Gilles Moec of AXA, who says the promise of structural reforms combined with the reward of EU pandemic funds had marked a break from decades of frustrating decline.

Even with the obvious pressure of geopolitics, and the giga-subsidies being thrown at gigafactories in France and Germany, Italy’s tapestry of small businesses has also learned to rebound from crises. In the same way that Rome moved quickly to adapt to the reality of war by diversifying its energy supply, Italian firms seem better equipped to survive hard knocks.

Eurogroup Laminations is an example of that. In the summer of 2016 when the UK voted for Brexit and when the Economist caricatured Italian banks as a bus teetering over a cliff-edge, the company secured financing to expand. Since 2017, the company says it’s developed 10 new products and nine new processes. When Covid hit, it closed for only three days. The gas crisis saw it pass on higher energy prices to its customers without losing them in the process.

Signs of cutting-edge manufacturing processes are all around the Baranzate site, buoyed by Italian tax credits for capital investment. While idly standing on the factory floor watching an automated assembly, I realize that I’m standing in the way of one of several impatient robots trying to do their job. The control room nearby is packed with screens and gauges that wouldn’t look out of place in a nuclear reactor.

“We do not have the size of Germany, or the state of France,” says Marco Arduini, Eurogroup’s CEO. “But we have entrepreneurship.” As the below chart shows, there’s been a narrowing of the euro-zone crisis gap between a productive North and uncompetitive South: Today Germany is where wage growth is outpacing productivity growth, while southern countries have seen increased productivity, according to Unicredit SpA.

There are two big challenges, however, that put this recovery at risk. The first is the obvious structural challenges that still remain. They include education, with Italy’s share of 25-34-year-olds with a tertiary qualification well below the EU average of 41%; corruption perceptions, seen as on par with former Soviet republic Georgia’s, and a chronically slow judicial system, which is being sped up as part of Italy’s commitment to unlock EU recovery funds.

The second is that old political habits may die hard as Meloni’s government faces a critical test in harnessing those EU funds. Getting the cash depends on doing the hard work of fulfilling investment and reform milestones, but progress is slow and there are fears that Meloni may tactically blame their failures on the Brussels establishment ahead of parliamentary elections next year. An increasingly skeptical European Commission delayed a 19 billion-euro ($21 billion) payment to the country in March to scrutinize what’s been done so far. (Excluding this, Italy’s received about 67 billion out of a 192 billion-euro total of loans and grants).

Economist Francesco Giavazzi, a former advisor to Draghi, warned last week in newspaper Corriere della Sera: “If the implementation of the (recovery plan) did not remain a priority for the government, there would be the risk of frustrating our ambitions — and those of Europe.” He has a point.

Keeping Italy’s recovery going will be critical not just for the country itself but for Europe’s hopes of closer integration and Western unity. At the corporate level, executives know the future could get messy: The aftermath of war has already forced EuroGroup Laminations to suspend and write down its Russian operations and it’s shifting its supply chain in keeping with a more polarized world along US-China lines. “This is not an easy time for Europe,” says Arduini. “We must stay united.” Politicians may have other plans.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

• Tax Evasion’s on the Agenda in Meloni’s Italy: Rachel Sanderson

• German Sneeze May Give European Stocks a Cold: Marcus Ashworth

• Juventus Lays Bare Football’s Rotten Finances: Chris Bryant

–With assistance from Mark Gilbert .

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering digital currencies, the European Union and France. Previously, he was a reporter for Reuters and Forbes.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion