September has been a month of grim news about the German economy. Inflation, which brings back the specter of the 1920s, remains stubbornly high. The Federal Statistical Office tells us that the inflation rate, “measured as the year-on-year change in the consumer price index (CPI), stood at +6.1% in August 2023.”

It is not just the Russia-Ukraine War that is causing inflation anymore. The Financial Times reports that, even excluding food and energy, inflation remains at 5.5% with higher wage pressures making it sticky, if not structural. Inflation is affecting all industries. In construction, costs are now 38.5% higher than the pre-pandemic early 2020.

An economy in deep crisis

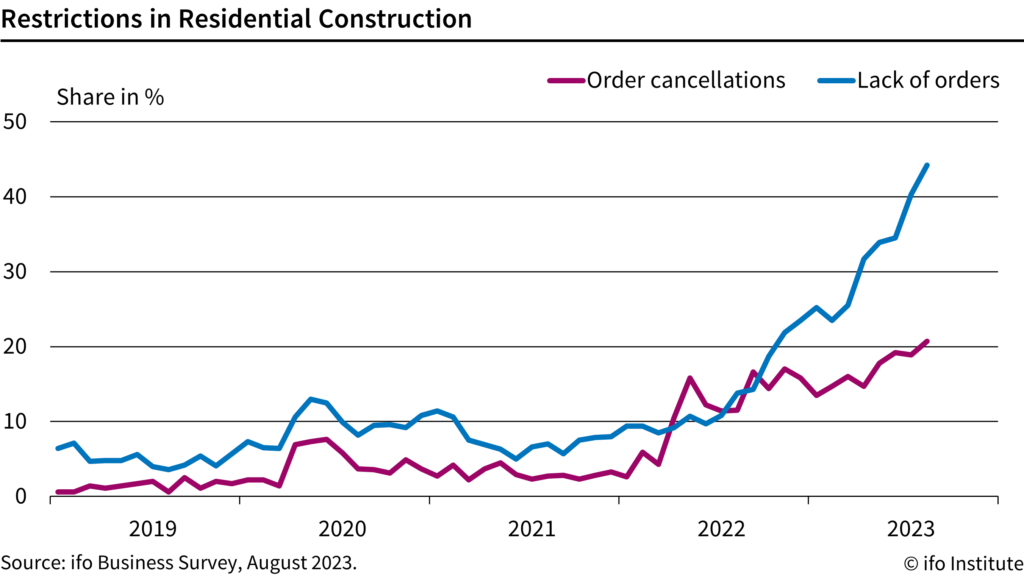

New orders for construction companies have dried up. Note that these orders are canaries in the coal mine and indicate confidence in the future. They are a forward-looking indicator for the economy. In August, the lack of new orders rose to 44.2%, up from 40.3% in July and a lot more than 13.8% in 2022.

Germany’s prestigious ifo Institute informs us that cancellations in residential construction have reached a record high. In August, 20.7% of companies reported canceled projects. The building industry is in trouble. Rising interest rates, soaring costs and weaker demand threaten to force many firms out of business. Several real estate groups are filing for insolvency. Germany is facing a shortage of 700,000 homes, and its housing crisis is bound to intensify. Last year, 295,300 dwellings were built, well short of the 400,000 target, and this year the gap will be worse.

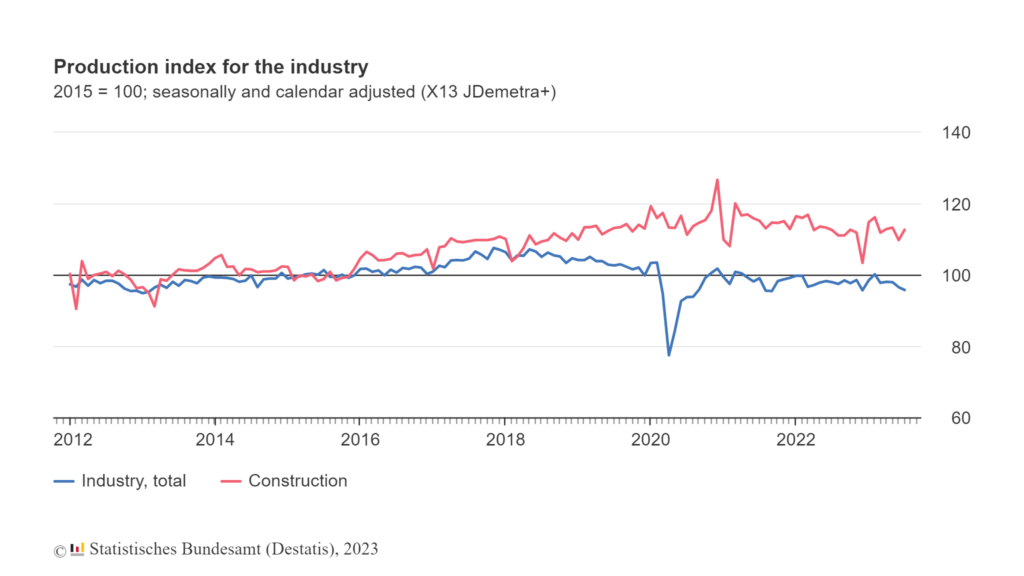

Industrial gloom is deepening too. The Federal Statistical Office’s September 7 press release reveals that industrial production “was down 0.8% in July 2023 month on month after seasonal and calendar adjustment.” Carmaking has declined dramatically. Rising energy prices have hit German industry hard, and Europe’s manufacturing superpower has shrunk or stagnated for the past three quarters.

Even before September, stories about the German economy have been pessimistic. On July 24, Reuters reported that “activity in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, contracted in July.” Investor confidence has been plummeting and foreign direct investment in Germany falling. The OECD expects the German economy to stagnate and be the worst performer among the major economies in 2023.

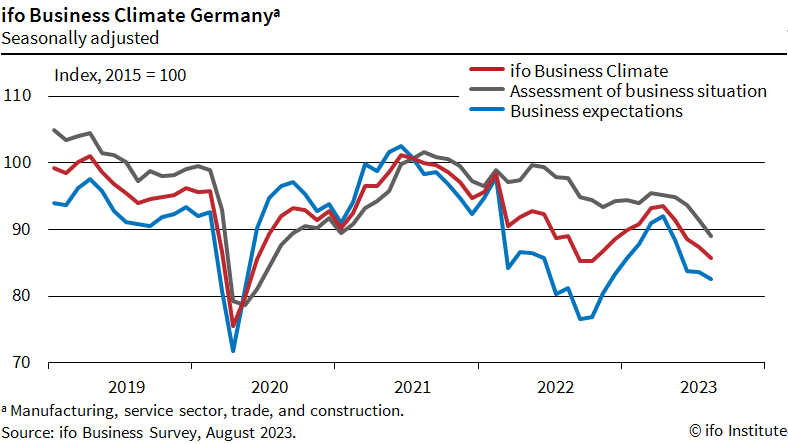

In August, the ifo Business Climate Index fell for the fourth consecutive time. Sentiment among German managers darkened in manufacturing, services, trade and construction. The index is at its lowest level since August 2020, and companies are increasingly pessimistic about the months ahead.

The Hamburg Commercial Bank’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (HCOB PMI) shows that German factory output has deteriorated at a rate not seen since 2009, the pandemic years excepted. Given that manufacturing accounts for a quarter of the German GDP, the fall in HCOB PMI is rather alarming.

On July 13, Matthew Karnitschnig in Berlin published a piece titled “Rust on the Rhine” in Politico. He described how “German companies are ditching the fatherland.” In Karnitschnig’s words, “Confronted by a toxic cocktail of high energy costs, worker shortages and reams of red tape, many of Germany’s biggest companies — from giants like Volkswagen and Siemens to a host of lesser-known, smaller ones — are experiencing a rude awakening and scrambling for greener pastures in North America and Asia.”

Politico has been grim about the German economy for a while. On November 10, 2022, Johanna Treeck published “Mittel-kaput? German industry stares into the abyss,” asking whether the prolonged energy crisis was causing “the beginning of the end for German industry.”

Not only manufacturing but also services are now declining. High inflation and rising interest rates are taking a toll on consumer confidence. Unemployment is rising. Once, the land of the Mittelstand — the small- and medium-sized industry that arose in the late 19th century and long powered the economy — was a world leader in innovation. That is no longer the case. In the World Intellectual Property Organization’s “Global Innovation Index 2022,” Germany only ranks eighth among world economies. Three European economies — Switzerland, the UK and the Netherlands — are ranked above it.

In a nutshell, Germany is in big trouble. Why?

Russia–Ukraine war spikes inflation

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, German industry increasingly relied on cheap Russian gas. Nord Stream 1 was a lifeline for Germany and Nord Stream 2 was set to begin operations too. Then, the Russia–Ukraine War upended German industry. Post-Nazi peacenik Berlin had not expected war to break out in Europe again. Germany had not diversified its energy supplies and was caught with its pants down.

In fact, Gerhard Schröder, Germany’s former chancellor, became the head of the supervisory board of Rosneft, a Russian oil giant, and was nominated to join the board of Gazprom, Russia’s state-controlled gas exporter, in his post-political career. Schröder had led the Social Democratic Party (SPD), Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s party, and served as chancellor from 1998 to 2005. His reforms in the early 2000s transformed Germany from “the sick man of Europe” into the continent’s economic engine.

Schröder refused to support George W. Bush’s 2003 Iraq War and, in the words of The Economist, was a “vocal advocate of Ostpolitik, a policy of rapprochement with the eastern bloc, including the then Soviet Union, conceived in the late 1960s by Willy Brandt, another SPD chancellor.” Many damn Schröder as Putin’s lobbyist today, and it is true that he has made big money from Russian energy giants. However, Schröder and many other Germans genuinely wanted to tie Russia into “an energy partnership of mutual dependence with Europe.”

All of that came to an end on February 24, 2022. Fuel, food, fertilizer and other commodity prices shot up. In particular, this supply-side shock caused inflation to skyrocket in Europe, especially because, unlike Canada and the US, the continent does not have substantial oil and gas reserves.

Germany suffered more than others even in Europe. Postwar Germany has been an idealistic nation where a strong environmentalist movement became politically powerful. After all, the Greens are currently in a coalition government with the SPD. In fact, Germany attempted a green energy transformation, the so-called Energiewende. As the war was stopping the supply of Russian gas, Germany was switching off all nuclear power.

Sadly for Germany, this move caused an energy scarcity. Germany simply did not produce enough renewable energy to take up the slack. This exacerbated the inflationary shock, and Germans ended up paying three times the international average for electricity.

Inflation increased input costs for manufacturing. In parallel, when central banks raised interest rates to combat inflation, the borrowing costs for industry shot up, as did the servicing costs on debt that was not locked in under old rates. For years, German industry had gotten used to low interest rates. Just like the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank had followed a policy of quantitative easing, which really means printing more money. This meant that the cost of capital was really cheap for companies. That cheap money era is over, and companies are scrambling to adjust to the new higher cost of capital.

Furthermore, the double whammy of increasing inflation and rising interest rates has hit consumer confidence hard. Even in the best of times, culturally Protestant Germans are savers, not spenders. Now, they are spending even less. They have more incentive to keep the money in the bank instead of spending it. Naturally, demand for goods and services is falling, and the economy is stagnating.

Chinese economy crashes, demand for German imports crashes too

In recent years, Germany has profited greatly from trade with China. After Deng Xiaoping opened up the economy in 1978, the Middle Kingdom grew spectacularly. Even as China became the factory of the world, Germany provided the machines that kept this factory running. Naturally, German exports to China boomed.

When this author traveled around the eastern seaboard of China in 2004, he met German businessmen everywhere. Almost all of them were exporting their goods to the Middle Kingdom. By the 20th century, China was Germany’s most important trading partner. Bilateral trade volumes amounted to $237 billion (€204 billion) in 2018.

On October 24, 2019, DHL published a piece titled, “As China Sneezes, Will Germany Catch a Cold?” It posited that “China’s weakening domestic economy and the ongoing trade tensions simmering between Washington and Beijing” would take a toll on the German economy.

DHL’s piece turned out to be prescient. As the US–China trade war has heated up, Germany has found itself squeezed in the middle. Increasingly, China sees Germany as a US ally. So, Beijing has been discouraging German imports into China implicitly and explicitly. In the first four months of 2023, German exports fell by 11.3% as compared to last year.

German ardor for China has cooled too. The Bundesbank, Germany’s renowned central bank, has warned German companies to cut exposure to China, warning that “the country’s business model is in danger.” No fewer than 29% of German companies import essential materials and parts from China. Rising US–China geopolitical tensions could disrupt this trade, bringing the German economy to a grinding halt.

Earlier in July, Germany’s 64-page “Strategy on China” attempted to chart a new policy towards the Middle Kingdom. It states, “China has changed. As a result of this and China’s political decisions, we need to change our approach to China.” This document goes on to say, “China is Germany’s largest single trading partner, but whereas China’s dependencies on Europe are constantly declining, Germany’s dependencies on China have taken on greater significance in recent years.” The new German strategy deems China a “systemic” rival and “accepts competition with China.”

Yet it is not easy for the land of the Mittelstand to decouple from the Middle Kingdom. German industry is still expanding in China. In July, BASF broke ground on a polyethylene plant at its seventh Verbund site in Zhanjiang, China. Even as this German manufacturing giant is investing $10 billion (€9.4 billion) in China, it is cutting 2,600 jobs and reducing production in Germany. A slowing Chinese economy has hurt BASF this year, with the company’s second-quarter net income falling to $533.38 million (€499 million) from $2.24 billion (€2.1 billion) in the same quarter a year earlier. When China sneezes, Germany indeed catches a cold.

Germany’s dependence on China made Scholz fly all the way from Berlin to Beijing on a state visit on November 4, 2022. The chancellor took along a gaggle of German CEOs to meet President Xi Jinping and Chinese authorities. Scholz’s visit was the first by a G7 leader to China in three years, and the chancellor flew back without even staying the night. Unfortunately for Germany, this visit has not yielded much in the way of results, and its new China policy has undercut Scholz’s pilgrimage to Xi. The German economy now faces a China dilemma, and there are no easy choices ahead.

US protectionism hurts Germany’s export-oriented economy

Since the 1980s, the champion of global free trade has suffered from deindustrialization. People in the rust belt are angry and hurt by the loss of manufacturing jobs. In part, this resentment fueled Donald Trump to the presidency. In office, Trump adopted protectionism as a means to revive American industry and repeatedly threatened tariffs on German cars. During Trump’s time at the White House, trade ties between the US and the EU remained tense.

Joe Biden’s presidency was supposed to change that. Instead, Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has upset America’s European allies. French President Emmanuel Macron sounded the bugle against the IRA, arguing that Europe needed an urgent response amounting to a whopping 2% of the EU’s GDP. Like China, the US is now subsidizing critical sectors of its economy. After decades, the US now has a full-blown industrial policy that subsidizes semiconductors, green energy and other technologies of the future. Posh think tanks in Washington are now breathlessly trumpeting the idea of GeoTech Wars.

After China, Germany is the country most hurt by the Biden administration’s new industrial policy. It has made timid Berlin ally with flamboyant Paris in calling for a joint EU response to the IRA. The Europeans argue that US subsidies tied to locally produced goods are worth $207 billion. This disadvantages European companies, contravenes World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and further erodes the world trade order.

As a result of the new American industrial policy, German companies are finding it increasingly difficult to export to the US. Note that exports matter a great deal to Germany. They comprise 50.3% of the GDP. In contrast, exports comprise only 10.9% of the US GDP. Last year, a German CEO and a member of the Bundestag, the German parliament, complained bitterly to the author about American protectionism in two separate conversations. Both remarked that the US was kicking Germany when this loyal ally was not on its knees but on its back.

A key reason for German economic troubles is that the post-1991 order is now dead. The US championed free trade and globalization for the last three decades. After the initially painful adjustment after reunification, the German economy boomed. Fueled by cheap Russian energy, Germany became a manufacturing powerhouse and an exporting superpower. In 2012, the BBC celebrated “a country whose inhabitants work fewer hours than almost any others, whose workforce is not particularly productive and whose children spend less time at school than most of its neighbors.”

What a difference a decade makes. Today, Germany is once again “the sick man of Europe” and The Financial Times reports a German manufacturer complaining, “everything is tired here.” In this post-globalization world, reshoring, nearshoring and friendshoring are the new buzzwords in the US. Washington, the architect of free trade and globalization, is turning its back on those ideas. Germany, which profited immensely from that system, is struggling to adapt.

Germany has its own self-inflicted wounds too

Like India and France, Germany is infamous for its red tape. There are innumerable forms to fill and boxes to tick before starting and while running any business. Approvals take too long. Environmental, labor and governance standards are unrealistically high, making entrepreneurship and business activity in Germany notoriously difficult.

Unlike India and France, the German political leadership is more candid about its economic problems. In an uncharacteristically bold speech, the mild-mannered Scholz declared in the Bundestag, his intention to “shake off the mildew of bureaucracy, risk aversion and despondency that has settled on our country over years and decades.” The trick for Scholz is to emulate Schröder and implement far-reaching reforms.

Unlike Schröder, Scholz does not command a majority in the Bundestag and is in charge of a fractious coalition, comprising the SPD, the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats. This traffic light coalition named after the colors of the three parties — red, green and yellow — has been plagued by infighting and has found it difficult to get anything done.

Meanwhile, Germany has many other problems that need to be addressed quickly. Manufacturers complain taxes and labor costs are too high. They are not only moving production to other EU members and Asia but also to the US and even the Brexit-afflicted UK. High taxation is also the reason talent hesitates from moving to Germany. In 2018, Deutsche Welle, Germany’s reputable state-owned international broadcaster, reported that if “you’re single with no kids and thinking about working in Germany” then “your tax burden will be 15 percentage points higher than the average among rich-income countries.”

In part, labor costs are high because Germany faces an acute shortage of workers. In June, the Federal Labor Agency’s annual analysis found that 200 out of about 1,200 professions surveyed had labor shortages in 2022, up from 148 in 2021. Germany is struggling to fill jobs “in nursing care, child care, the construction industry and automotive technology, along with truck drivers, architects, pharmacists and information technology specialists.” Improving labor immigration is high on the government’s agenda, but little progress has been made so far.

Germans work 1,341 hours per year, the least in the OECD. In contrast, Americans work 1,811 hours annually. Managers complain of a decline in Germany’s fabled work ethic. Many have confided to the author that the quality of candidates for Germany’s impressive apprenticeship programs has fallen significantly from even a decade ago. The Financial Times has also heard similar complaints.

For decades, much of the world has admired Germany’s dual education system. It combines vocational training with apprenticeships. This has made German labor highly skilled and its industry competitive. Now, fewer people are enrolling in vocational training and apprenticeships. In 2022, 469,000 people took up apprenticeships, approximately 100,000 fewer than in 2011.

Germany’s declining demography amplifies its labor shortages. As per the Federal Statistical Office, deaths exceeded births by 327,000 in 2022 and there were just 1.53 births per woman in 2020, well short of the replacement level fertility of 2.1 births per woman. This means that Germany’s population is shrinking and it simply does not have enough people to work in the various sectors of its economy. In May, Deutsche Welle published a story titled, “Germany’s labor crisis is an economic time bomb.” The government has admitted that it will lack seven million workers by 2035.

An aging population causes a rising pension burden as well potentially higher taxation on a shrinking labor force to support Germany’s rather generous welfare state. This means that most skilled workers are likely to prefer to immigrate to countries like the US, Canada and Australia, which have the English language advantage as well.

Fair Observer’s economist author Alex Gloy, also points out how Germany has missed the boat in software and digitalization. According to Gloy, “the only German software company to speak of is SAP, which was founded 1972. Germany has no social media company. The only dynamic sector is delivery startups. But you have 30 of them in Berlin, right next to each other. This makes absolutely no sense.”

Germany’s weakness in the digital economy and infrastructure needed for this economy has made it rely on Huawei for 5G. That is an apple of discord with Uncle Sam, which wants Germany to use more expensive American infrastructure instead. The US has also pressured Germany to increase its defense expenditure for years. Germany finally agreed to do so in the light of the Russia-Ukraine War. Yet this increased expenditure will increase the tax burden for Germans unless Berlin imposes austerity measures on its citizens.

The German economy needs to make major reforms and painful decisions. To steal a word from Scholz’s February 27, 2022 speech to the Bundestag, the economy faces a Zeitenwende — a historic turning point — because business as usual in the post-2022 world simply will not suffice. Sadly, Scholz’s weak traffic light coalition has little appetite for tough decisions and the German economy faces a few painful years ahead.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.