European finance ministers on Wednesday afternoon (20 December) reached a provisional agreement on the bloc’s spending and debt rules.

“We will 100 percent reach a deal,” said French finance minister Bruno Le Maire on social media after he tried to iron out the last disagreements with his colleague from Germany — with whom he has been at odds for most of 2023.

According to German finance minister Christian Lindner, the two had made headway on minimum safeguards to ensure annual deficit and debt levels while leaving room for (green) investments.

“This is a chance for a political agreement at the finance council,” Lindner, from the neo-liberal Free Democrats in the German governing coalition, said on social media.

But a representative from the Spanish presidency currency chairing the negotiations said there are still “some elements left over for ministers to discuss”.

EU ambassadors will meet again on Thursday to finalise a negotiating mandate based on the preliminary agreement, paving the way for interinstitutional negotiations set to take place in January.

EU spending and debt rules, known as the Stability and Growth Pact, were suspended since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic to allow governments to spend their way out of the crisis and support households and businesses.

The suspension, combined with a giant monetary stimulus package from the European Central Bank, prevented the pandemic from morphing into a giant financial crisis.

Since the end of last year, leaders have tried to agree on new rules because the old ones were deemed too strict and were, therefore, never implemented.

The rules were violated 114 times between 1999 and 2016, but there were never any consequences.

Some of the final details ministers have to agree on are safeguards. In the last negotiating text seen by EUobserver, countries with debt-to-GDP ratios exceeding 90 percent must reduce it by one percentage-point per year. For those with debt between 60 and 90 percent, it will be half a percentage-point per year.

Annual deficits should stay below 1.5 percent. Countries overstepping both the 60 percent debt ratio and the three percent deficit limit under the new ‘excessive debt procedure’ will have to reduce deficits by 0.5 percent per year.

There is still some uncertainty on how this will be calculated precisely.

One group of countries, led by France, has wanted to exclude both interest payments and green investment expenditures from the calculation of the 0.5 percent adjustment minimum.

“This would make a big difference, [as] France’s interest payments are projected to rise by 0.2-0.3 percent of GDP per year as higher interest rates push up the average cost of borrowing,” Zsolt Darvas, a senior research fellow at the Brussels-based think tank Breugel wrote in an analysis last week.

Depending on the flexibility of the rules when it comes to allowing new growth-boosting investments, Bruegel’s projected spending limits will likely require half of EU countries to enter deficit proceedings next year.

And the think tank advised ministers to exclude green investment spending from the deficit reduction calculation.

This may also boost growth. For example, a recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows that green investments have an above-average positive effect on economic growth compared to other public investments.

Not all are happy

While French and German negotiators may have agreed, Italy, Portugal, and Greece are still unhappy with the compromise.

“There have been some steps forward but not on Italy’s position,” said Italian finance minister Giancarlo Giorgetti after last week’s negotiations, adding that he believed clinching a deal this week was “unlikely.”

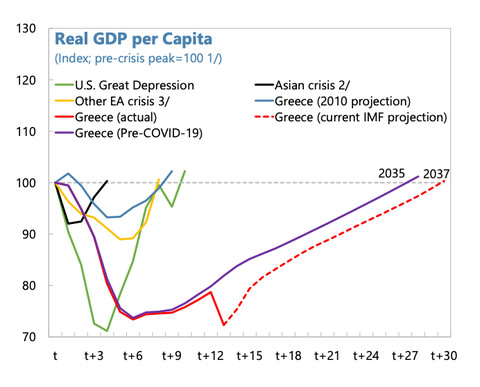

Italy, Portugal, Greece and Spain suffered gruelling austerity for most of the 2010s, partly enforced by the EU.

While these countries cut their budgets the most between 2009 and 2019, they also saw the largest increases in their debt-to-GDP ratios, leading many to criticise spending cuts as an effective way to bring down debt.

The IMF has also found that fiscal consolidation historically does not reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio but increases it.

Focus on growth

In a discussion hosted at the European Central Bank on Monday, the influential economist Oliver Blanchard suggested rules that use debt trajectory as a basis for stability are more effective than rules that are aimed to keep debt at a specific ratio.

If the growth rate exceeds interest rate payments, debt eventually stabilises or drops.

“We know countries can get away with 250 percent,” he said, referring to Japan. “Focusing on debt [ratio] is wrong. Focusing on the trajectory is right.”

This article has been updated