Europe is closely observing the Turkish elections as a change in leadership could lead to a reset in Türkiye-EU relations

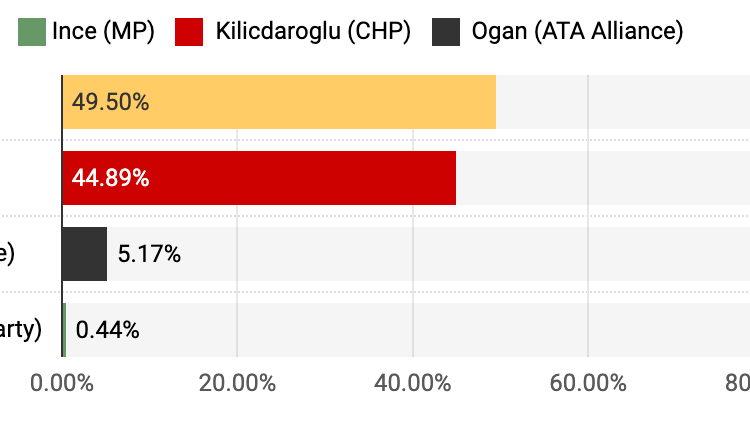

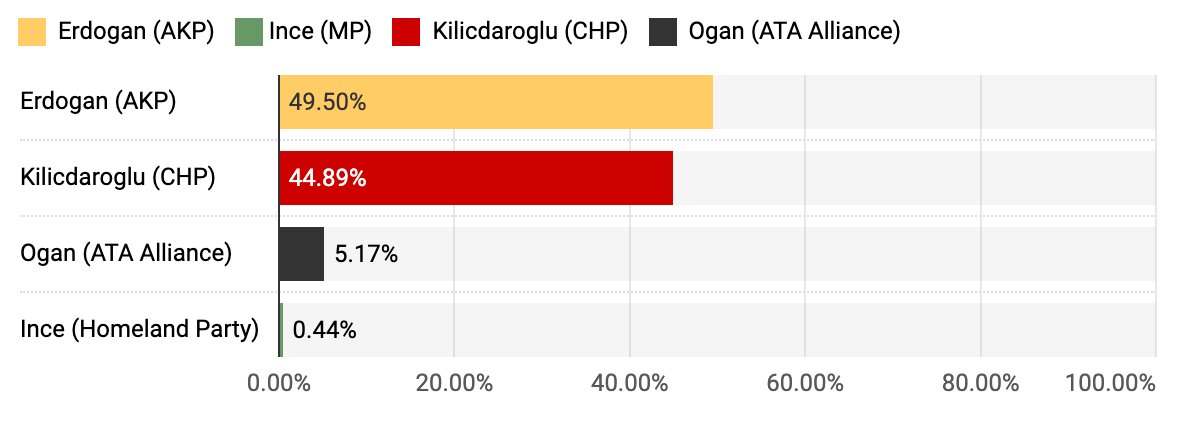

The presidential and parliamentary elections in Türkiye were held on 14 May 2023. The elections come at a pivotal time for Türkiye, as the country struggles with a spiralling economy, post-COVID recovery, and devastating February 2023 earthquakes. As the government’s response was deemed to be lacking, these elections were seen as a referendum on President Erdoğan’s term. While the earlier polls suggested that the Opposition leader Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu was in the lead, the results ended with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan getting 49.5 percent of votes as opposed to 44.8 percent of votes received by Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu. As both candidates failed to achieve the majority required to form the next government, the second round of elections will be held on 28 May 2023.

Election Results

As Türkiye’s relations with the European Union (EU) and its member states have been under stress over the past few years, these elections have also become a litmus test for the future trajectory of the partnership.

State of EU-Türkiye relations

EU-Türkiye relations have witnessed a downward trend in the past decade. Their partnership was defined under an association agreement in 1963, which led to the signing of a Customs Union agreement in 1995. While Ankara applied to join the European Economic Community in 1987 and was declared a candidate in 1999, it was not until 2005 that the accession negotiations were launched. As President Erdoğan shifted his policy directions towards a more centralised leadership, the accession process was stalled in 2018 over issues related to the rule of law, human rights, and concern over the independence of the judiciary. In 2021, the European Parliament had called on the EU Commission to formally suspend talks with Türkiye because of “the authoritarian interpretation of the presidential system, lack of independence of the judiciary and continued hyper-centralization of power in the presidency.”

While enlargement remains a key issue of discussion, migration has also emerged to be a bone of contention. During the migration crisis of 2015, over 1 million migrants reached European shores. The EU and Türkiye signed a migration deal in 2016, under which illegal migrants were returned to Türkiye, and Ankara would take steps to prevent migration flow to Europe. In return, the EU would first, resettle Syrian refugees on a case-by-case basis; second, pay Ankara 7 billion euros as aid for Syrian refugees; third, update visa regulations schemes for Turkish nationals; and fourth, relook at and update the customs union agreement. While the agreement resulted in a reduction in the number of migrants crossing over to Europe, Türkiye has been discontented with the European response and has called for a revision of the deal. Tensions were fuelled in 2020 when Türkiye opened its border with Greece and allowed migrants to cross over. The EU had called this “Türkiye’s use of migratory pressure for political purposes.”

The European Parliament had called on the EU Commission to formally suspend talks with Türkiye because of “the authoritarian interpretation of the presidential system, lack of independence of the judiciary and continued hyper-centralization of power in the presidency.”

Another key issue is the question of the sovereignty of Cyprus, which had been partitioned in 1974 between the Greek Cypriot government and the Turkish Cypriot government. The tensions grew in 2019 when the Turkish government started to explore and drill energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean. Both Greece and Cyprus had called out Türkiye for infringing upon their continental shelf and exclusive economic zones. The tensions led to the suspension of Association Council meetings and other high-level dialogues between the EU and Ankara.

Even with NATO, relations have witnessed a downward trend. According to public opinion polls, the majority of the Turkish population does not trust the alliance to stand by Ankara in case of a conflict. Relations hit rock bottom in 2017 when Türkiye opted to buy the Russian S-400 missile system, which was deemed incompatible with NATO’s defence systems on the grounds of interoperability. This led the United States (US) to suspend Ankara’s participation in its F-35 programme and also put sanctions on the country. Another source of irritation for the Transatlantic Alliance is Türkiye’s refusal to ratify membership bids of Finland and Sweden. According to Ankara, both Nordic countries have provided safe havens to individuals and terrorist organisations—or so it deems—and wants them to take strict actions against the groups, including extraditions of alleged Kurdish fighters. While it cleared the way for Finland to join in April 2023, Sweden’s bid is still pending.

Relations hit rock bottom in 2017 when Türkiye opted to buy the Russian S-400 missile system, which was deemed incompatible with NATO’s defence systems on the grounds of interoperability.

Also, Türkiye has come to play a pragmatic role in the Ukraine crisis. On the one hand, it has supplied weapons, especially the Bayraktar drones to Ukraine, and, on the other, it has refused to join the Western sanctions on Russia. Ankara also hosted negotiations between the two in the early part of the conflict. This balancing act has allowed Türkiye to reach out to both President Putin and President Zelenskyy to seek diplomatic breakthroughs such as brokering a grain export deal and the exchange of prisoners—keeping the channels of communication open between Russia and Ukraine.

Will election results change anything?

While EU and Türkiye relations have been marred by one crisis after another, relations have somewhat achieved a kind of normality since 2020. This was primarily driven by the decline of hostilities in the Eastern Mediterranean as well as positive political overtures between Greece and Türkiye. This was also compounded by the fact that tensions between the US and Türkiye reduced post-American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and the role that Ankara played in brokering certain agreements between Ukraine and Russia during the crisis.

However, the public opinion in Türkiye remains anti-Western—with 58.3 percent of the respondents calling the US the biggest threat and only 33.1 percent of the respondents preferring the EU countries as the partner of choice, as opposed to 37 percent in 2021. While the support for EU membership remains high at 58.6 percent, however, 53 percent believe that the EU has no intention of accepting Türkiye as a member state. Similarly, the enlargement fatigue in the EU also needs to be factored in. Member states such as France and Austria appear ambivalent about restarting the discussions.

The accession to the EU will remain in the deep-freeze, the transactional partnership on the Syrian migrants issue would continue, and getting the disbursal of 7 billion euros pledged by the EU and international donors for recovery from the February 2023 earthquakes would remain a priority.

The elections in Türkiye are being closely watched by the EU, primarily because they will define the future of the relations between the two partners. There is hope that a change in leadership will affect the conversations on important issues such as migration, security, energy, and the policy orientation on Russia. This is primarily because the Opposition candidate Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu, during his campaign, had called for normalisation of relations with the West, including restarting the process of accession and restoring the trust of its allies. He had also called for a review of the purchase of the S-400 missile defence systems and to restore Türkiye’s position in the US’ F-35 programme. While these steps will be welcomed by the EU, however, the main test for Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu would remain the reversing of the constitutional and parliamentary reforms, and getting the economy back on track.

However, if President Erdoğan is able to secure another term, relations will follow more or less a similar pattern as seen in the past few years of balancing Turkish interests with the East and the West. In short, the accession to the EU will remain in the deep-freeze, the transactional partnership on the Syrian migrants issue would continue, and getting the disbursal of 7 billion euros pledged by the EU and international donors for recovery from the February 2023 earthquakes would remain a priority. For its part, the EU would continue to stall visa-free travel for Turkish citizens over Ankara’s failure to meet criteria, there will be limited movement in updating the customs union agreement; and there will be continued support for Turkish diplomatic efforts to safeguard the grain deal between Russia and Ukraine. In short, the relations will continue to be characterised as walking a diplomatic tight-rope. Therefore, whatever the outcome may be, these elections highlight the need for the EU and its member states to assess their partnership with Türkiye and see how much they can reset the future trajectory of relations.

Ankita Dutta is a Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation