Markets have been reassessing Bank of England rate hikes

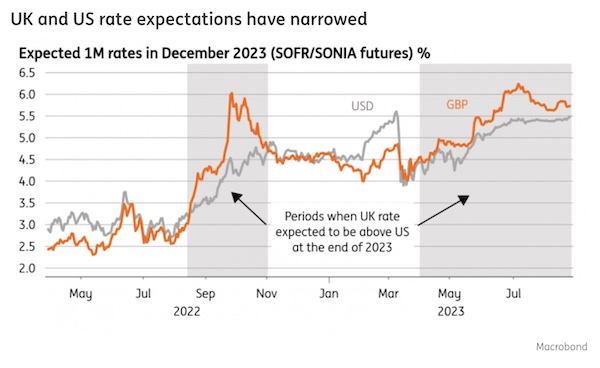

Rewind to the start of the summer, and the view that the UK had a unique inflation problem had become very fashionable. At its most extreme, market pricing saw Bank Rate peaking at 6.5%, some 125bp above its current level. Since then, this story has begun to lose traction. The differential between USD and GBP two-year swap rates, a gauge of interest rate expectations, has halved.

That reflects the growing reality that the UK inflation story looks less of an outlier than it did a few months back. Like most of Europe, food inflation has begun to slow, and further aggressive falls are likely judging by producer prices. Consumer energy bills fell by 20% in July, and another 5% decline is baked in for October. The Bank of England itself is now describing the level of interest rates as “restrictive” – a statement of the obvious perhaps, but nevertheless tells us that policymakers think they’ve almost done enough with rate hikes.

A September hike is likely but November is less certain

Still, we’re not quite there yet, and recent inflation data has continued to come in on the upside. Private sector wage growth – measured on a three-month annualised basis – is running at a cycle-high of 11%. Services inflation also edged higher in July, although this was partly attributable to some unusual swings in specific categories rather than broad-based moves. A September hike is therefore highly likely.

Whether markets are right to be pricing another hike for November is less certain. We’ll only get one round of CPI and wage data between the September and November meetings. Wage growth is unlikely to have slowed much, but we’re hopeful for early signs that services inflation is inching lower. Various surveys suggest few service-sector firms are raising prices, and we think that reflects the sharp fall in gas prices.

A lot also hinges on whether we continue to see signs of weakness in economic activity. Like Europe, the UK’s PMIs look worrisome and will have prompted some pause for thought at the Bank of England. The jobs market is also cooling, and the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio – which BoE Governor Andrew Bailey has consistently referenced – is closing in on pre-Covid highs. There’s also been an ongoing improvement in worker supply.

We’re now at a point where survey numbers and various bits of official data suggest that both economic growth and inflation are losing steam. The inflation and wage growth figures aren’t there yet, but these are lagging perhaps most out of all economic indicators. A November pause isn’t guaranteed, but it remains our base case.

To some extent, we’re splitting hairs. In the bigger picture, the Bank is becoming much more focused on how high rates need to go – and instead, the central goal will increasingly become keeping market rates elevated long after it stops hiking. Any further rate hikes should be seen as a means to that end.

Source: ING