This is Armchair Economics with Hamish McRae, a subscriber-only newsletter from i. If you’d like to get this direct to your inbox, every single week, you can sign up here.

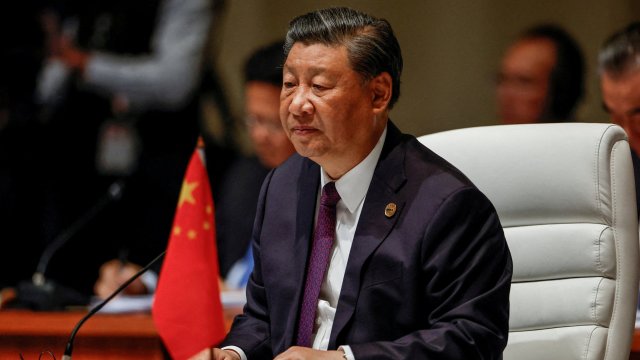

Maybe China won’t become the world’s largest economy after all. This weekend, the heads of government of the G20 nations meet for an economic summit in New Delhi, and there will be one notable absence: Xi Jinping. Instead, China will be represented by Li Qiang, the premier, who is the second-ranking member of the party’s politburo.

Less surprisingly, Vladimir Putin is not going either. But both of them led their delegations for the rival Brics summit two weeks ago in Johannesburg, albeit with the Russian president attending by video. The Brics acronym was coined by Jim O’Neill, now Lord O’Neill, when he was chief economist at Goldman Sachs and stands for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa being the largest so-called emerging economies. Led by China, it has since been developed into a rival club to the G7, the large developed economies, and the G20, an expanded version which includes the big emerging economies too. Six other countries, Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, join next January.

Two rival blocs

So, you can see what is happening. China is setting itself up to be the leader of the emerging world, as the US is the leader of the developed world. When it passes the US to become the world’s biggest economy it will then be in a position to organise world trade, encourage countries to use its currency, the renminbi, rather than the dollar for international trade, and bypass institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank that are dominated by the US and arguably are tools of the West. In short, it wants to run the world economy.

But this only works if China does indeed pass the US in economic size. Until a few months ago, most economic forecasts expected this to happen some time in the 2030s. Look forward to 2050 and PwC projected that the pecking order then would be China first, India second and the US third. Goldman Sachs recently revisited their original study of the Brics and forecast that China would indeed pass the US around 2035, and that while India would still be number three behind the US in 2050, it too would pass it around 2075.

Times are changing

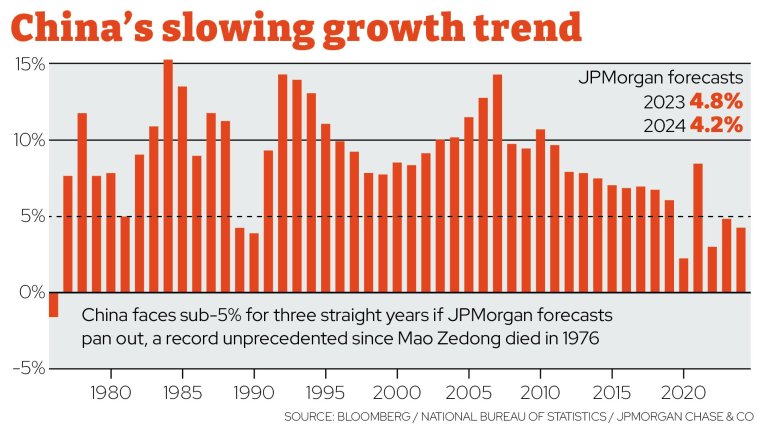

But in the past few months, the mood has shifted. The Chinese economy is in trouble. Its population has started to shrink. So maybe China will not pass the US in economic size after all. Or if it does for a few years, America will soon start to pull ahead again, to remain the dominant economy through the 21st century as it was in the 20th century. This week some new forecasts by Bloomberg Economics confirm this view. Their central projection is that if China does pass the US it will not be until the 2040s and then only by a small margin before falling back again. Its more negative projections suggest China will never become number one. Its economy will grow much more slowly than expected even a year ago.

There are a number of reasons for this. In the short-term China faces a property crisis, with falling prices plunging and large building companies in danger of going under. The country has simply borrowed too much and built too much. When the economy was growing at 6 per cent or 7 per cent a year, eventually all the unsold homes would be mopped up. But now it is growing at most by 3 per cent, probably less, and much of its past activity seems to have been a mirage. Exports have been falling and Western companies are seeking to diversify towards other emerging nations, notably India.

In the medium-term, it faces being frozen out of high-tech electronics by the US ban on exports. Its great mobile phone producer Huawei does seem to have gotten around the ban by replacing US chips with Chinese ones in its latest high-tech phone, but there are reasonable doubts that if China is excluded from top-end US technology, it will not be able to make the transition to full advanced economy status. It is brilliant at some things, including making electric cars, but weak at others. And there are, of course, political risks that will inhibit foreign investment there.

A falling population

However, the most powerful argument for expecting Chinese growth to flag is demography. Shanghai, its largest city, has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, an average of 0.7 babies per mother. We do not know how fast the population of the country will decline but we do know that a fast-falling population will change the nature of the economy. Not only will growth fall; more and more of economic activity will have to go looking after the elderly population. Remember, the reason why China was expected to become the largest economy was the number of its people, not the wealth-per-head, which was always going to be much lower than that of Americans.

Good news for us

What does all this mean for the UK? The modestly good news is that we are not that dependent on the Chinese market, unlike Germany, where its manufacturers are suffering because of the switch to electric cars. VW was once by far the biggest car producer in China but now is down to about 10 per cent of the market.

This does not mean we should step away, but it does mean that we should try to build trade links with China’s rivals. That’s the US of course, which is our biggest single export market, but also India as it grows in economic heft – a country to which we are culturally much closer. We should expect no special favours from India, and should seek a good relationship with everyone. But there are many reasons why strategically we are quite well-placed in the battle for leadership in the next couple of decades.

Need to know

I became very interested in the original Goldman Sachs exercise when it came out 20 years ago for all sorts of reasons but particularly because it fitted in with my work trying to chart the transfer of economic might from the developed world to the emerging economies – or emerging and frontier economies as we now call them.

So I wrote a lot about it. In particular, I felt that the growth of China and India was returning them to their rightful place in the world, for until the industrial revolution they were the world’s two largest economies by a huge margin. Besides, surely it must be right to celebrate the fact that economic growth was bringing hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and enabling them to have middle class lifestyles and opportunities.

Groundbreaking research

That original Brics paper turned out to be what I think is the single most consequential piece of economic research in my lifetime. It was a simple growth model, contrasting the outlook for the G7 with that of the Brics, and you can download it here. In detail it was flawed. I have tended to rely instead on the work of HSBC, which also looked at 2050, and then in 2018 did an update with more countries, looking to 2030. There is a reference here.

What I had not envisaged was the political clout of the research. There is now the Brics summit (the “s” now being a capital letter as South Africa joined the original four), a Brics development bank, now renamed the New Development Bank, the extension of membership taking place next year, and so on.

A reset

My worry, however, is the way the whole thing has become contentious. It is reasonable for the emerging and frontier economies to have their voice heard and their growing importance recognised. But if the world does split into two rival blocs – I very much hope it won’t – then those emerging nations will suffer the most.

My feeling is that the world has a difficult decade to get through, but if it can do so with reasonable harmony, it will be much easier in the 2030s. Once China recognises that it will not be number one, if that is indeed the case, then it can switch attention to providing a better life for these people. In that sense, I am encouraged by this research.

A further point that would have been nice to develop is the environmental implications of slower growth in China. Fewer resources will be needed to give its people a decent life. That must be welcome too.

The thing to look for in the years ahead will not be further economic projections but any evidence that the Chinese leadership is adjusting down its expectations about the country’s role in the world. At the moment, it is moving in the other direction, but at some stage, there will have to be a reset. The huge question is the nature and timing of that reset. But that is a story for another day!

For anyone interested in these issues, they are widely discussed in my new book, The World in 2050, published by Bloomsbury (£11.69)

This is Armchair Economics with Hamish McRae, a subscriber-only newsletter from i. If you’d like to get this direct to your inbox, every single week, you can sign up here.