Three years on, the lesson of the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund is that building economic resilience is a long-term endeavour.

To soften the economic shock in early 2020 of the Covid-19 pandemic, governments around Europe engaged in negotiations over the design and size of stimulus packages. It was widely acknowledged that these mitigation efforts should not only aim for short-term recovery but also strive to make Europe’s economies more resilient in the long-term. Hence the name of the instrument agreed by the European Union—the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF).

On February 19th 2021 the €723 billion package of grants and loans came into force. Roughly half-way through its implementation, we can make a preliminary assessment of how much the facility has delivered on its promise, to ‘build back better’.

This shows positive signs: despite the unprecedented challenges faced by the EU since 2020, the overall economic resilience of member states has not been impaired. The RRF appears to have played a part in this stability. Moreover, those countries—such as Italy and Spain—which took the opportunity to develop comprehensive national plans for investment and reform, centred on the available money, have demonstrated remarkably swift implementation of those plans and progress towards their targets.

Challenges in the implementation of the RRF remain, including lack of flexibility to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. But the design of the facility has fostered a national ownership which was previously lacking and which is essential if member states are to stay the course for long-term goals.

Holistic understanding

In this turbulent era, more resilient economies have emerged as a key objective of economic policy-making. Global bodies such as the United Nations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the EU have all encouraged economic resilience. We urgently need economies which are capable of weathering major socio-political disruptions and economic downturns while fostering long-term prosperity.

Become a Social Europe Member

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month. Your support makes all the difference!

A holistic understanding of resilience transcends mere recovery: it encompasses the capacity of economies to absorb, recover from and adapt to shocks in ways that make future disruptions less likely. Economic resilience should thus not be understood as merely ‘bouncing back’ from crises but ‘bouncing forward’ towards a greener, more stable and prosperous economy. This holistic perspective envisages an economy that serves the wellbeing of current and future generations within the constraints of our planet’s resources.

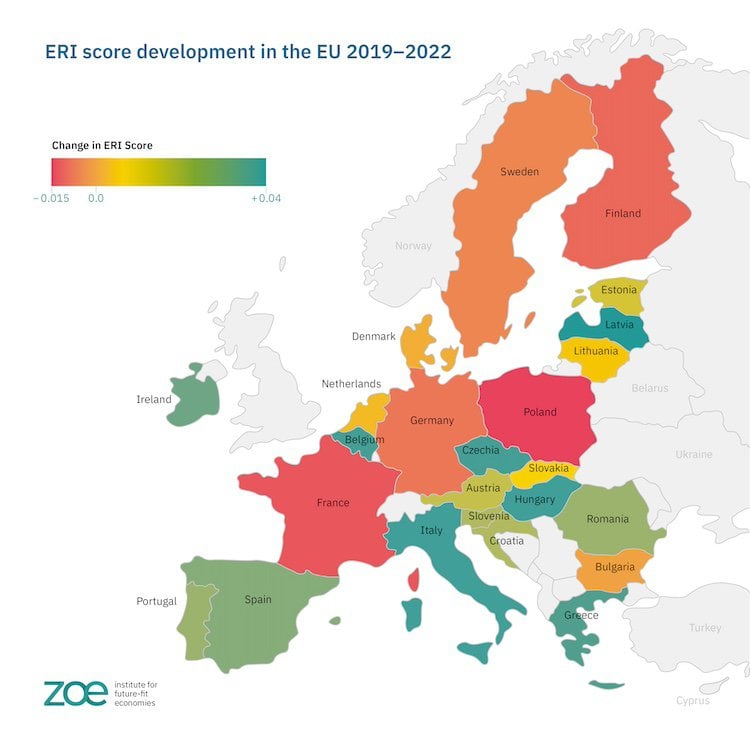

To quantify and compare economic resilience, the ZOE Institute for Future-fit Economies developed an Economic Resilience Index. A ranking of EU economies for their resilience using the index’s methodology finds considerable disparities among member states: Sweden, Denmark and Finland lead, while Romania, Greece and Bulgaria lag behind. Because the EU can only be as resilient as its least resilient member state, this gap underscores the need for concerted efforts to bolster resilience across the region and particularly in the countries most exposed.

Resilience undiminished

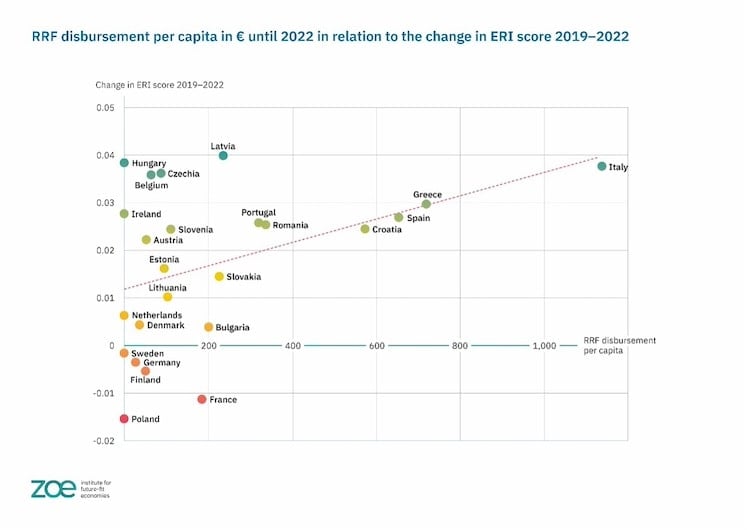

New results from the Economic Resilience Index—presented in the charts below—reveal that the overall resilience of the bloc did not diminish from 2019 to 2022 and, indeed, countries which received more RRF funding per capita increased their resilience on average more than those receiving less. This is particularly significant given these countries’ past difficulties in drawing down EU funds: Spain, for example, was bottom of the table for absorbing European structural funds in 2014-20, when it made use of only 39 per cent of what was on offer, but at the mid-point of the RRF it has received more than half of its approved grants and is the country with the third highest disbursement.

At this point it thus seems that—in the face of the pandemic, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis—the RRF has been contributing to economic resilience, as intended. This underlines the importance of access to funding for the least resilient member states to improve the EU’s collective performance.

More specifically, the quality of planned reforms and investments seems an important indicator of member states’ ability to enhance their resilience, alongside the amount of funding received. In particular, a higher degree of policy integration, especially in social and cohesion policies, correlates with improved resilience.

Looming fiscal cliff

With all this in mind, it is worrying that member states face a looming fiscal cliff in 2026 when the RRF runs out. Enhancing the future-preparedness of economies is a marathon, not a sprint, and without access to funds post-2026 there is a risk that the long-term positive effect of the RRF on resilience will be lost, beyond its short-term recovery role.

At the same time, revised EU fiscal rules soon to be reapplied will oblige member states to reduce high levels of public debt. This will require more prudent spending when the need for it remains high—not least to finance the European Green Deal.

A recent estimate puts the additional public investment needed only for the decarbonisation of EU economies at €260 billion per year, which is above what the RRF currently provides. Add to this the geopolitical uncertainties, including shifts in global trade partnerships with China and the United States and possible disruptions in international supply chains, and the need for investment is even more profound.

Follow-up instrument

The case for a follow-up instrument to help member states sustain momentum towards more resilient economies is compelling. Such a longer-term instrument would build on the successes of the RRF, extending its time horizon and upgrading its capabilities so it can better address evolving challenges.

The upgrade could include the integration of targets for social spending as well as a safeguard to ‘do no social harm’. Just as the RRF has incentivised green spending, setting benchmarks for social expenditure would help prioritise initiatives to foster social progress and cohesion—indispensable components of lasting economic resilience.

Beyond 2026 the EU needs to ensure that all member states, particularly those with limited fiscal capacity, have access to resources for vital reforms and investments for resilience-building, a common priority of the EU. Born out of crisis, the Recovery and Resilience Facility seems so far to be living up to its name and enabling countries not only to bounce back but to ‘build back better’. But there is still a long way to go and longer-term thinking is needed if the positive trends in economic resilience are to be maintained.