NEW YORK – The US economy added an unexpectedly large 336,000 jobs in September, buoyed by the largest peacetime budget deficit in history and a flood of transfer payments in the form of federal hand-outs to individuals.

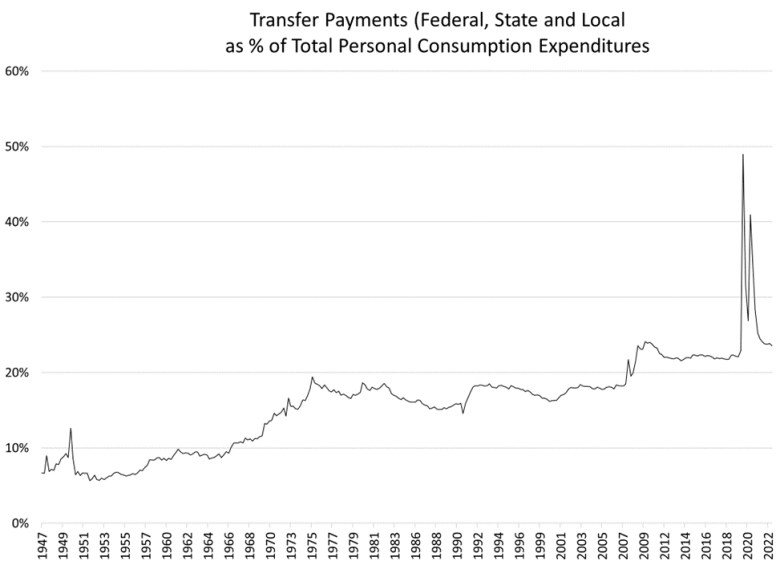

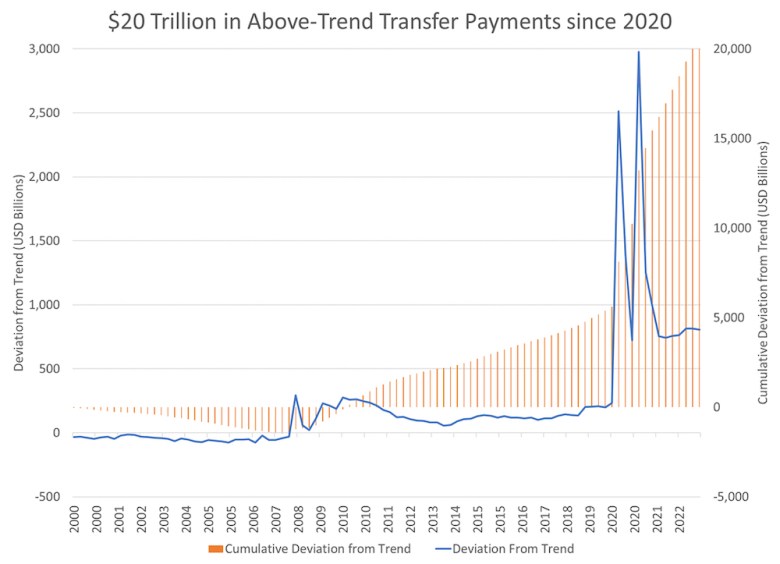

Almost one-quarter of every dollar spent in the United States for personal consumption today comes from a federal government check. Excess payments to Americans (above the long-term trend) amounted to $15 trillion during the past four years, more than half the annual output of the US economy.

With a net foreign asset position of negative US$16 trillion and a chronic trade deficit, the United States has to borrow from or sell assets to foreigners to fund itself. This could lead to an Italy-like vice in which the cost of servicing existing debt at perpetually high yields paralyzes the federal government—potentially much sooner than Washington politicians seem to understand.

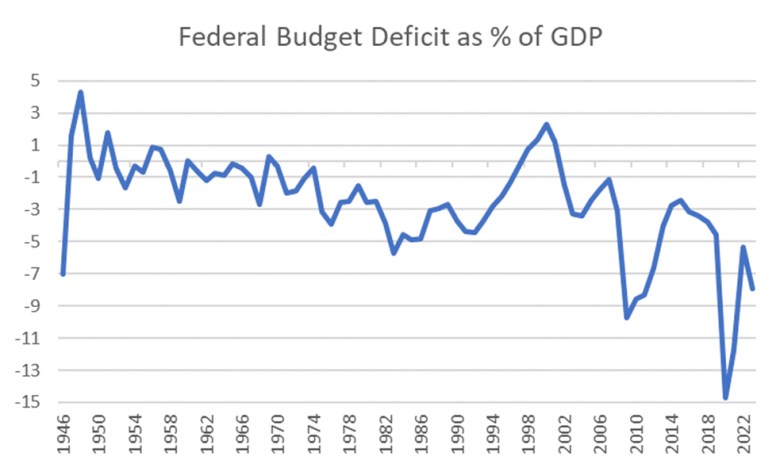

The flood of federal largesse has produced an economy where everyone is rich, but no one can afford anything. The federal government will borrow about $2 trillion in 2023, or nearly 8% of the year’s gross domestic product (GDP), a deficit only exceeded during periods of economic breakdown such as the 2008 Great Recession and the Covid recession of 2020. Nothing like this has ever occurred during an economic expansion.

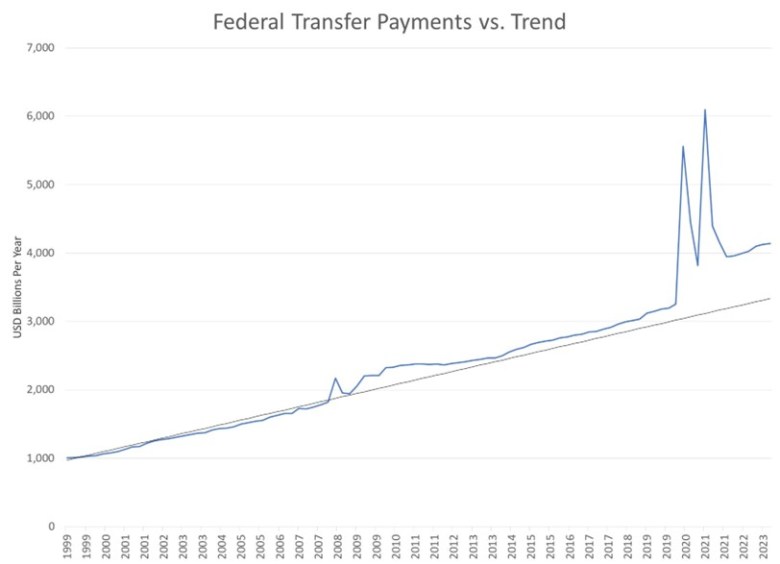

Most of the increase in the deficit stems from payments to individuals. In response to the national shutdown in April 2020, the Trump administration passed an emergency $3 trillion stimulus package. The Biden administration followed this with even bigger stimulus while the economy was recovering. The level of transfer payments remains $1 trillion a year higher than trend, as shown in the chart below.

Cumulatively, federal payments to Americans in excess of trends have amounted to $20 trillion since 2020, or about three-quarters of the annual output of the US economy. Transfer payments, almost all from the federal government, now comprise 24% of personal consumption expenditures, compared to just 6% in 1946.

What can’t go on forever, won’t, in economist Herbert Stein’s classic formulation. The United States has to borrow $2 trillion each year at increasingly higher interest rates, costs that will eat up nearly $1 trillion of spending in 2023. The Peterson Institute think tank in Washington, DC, estimates that an aggregate $71 trillion in interest costs will suck up 35% of all federal spending by 2053.

The supply of Treasuries required to finance the deficit became the biggest driver of higher bond yields during 2023. This can be illustrated through regression analysis.

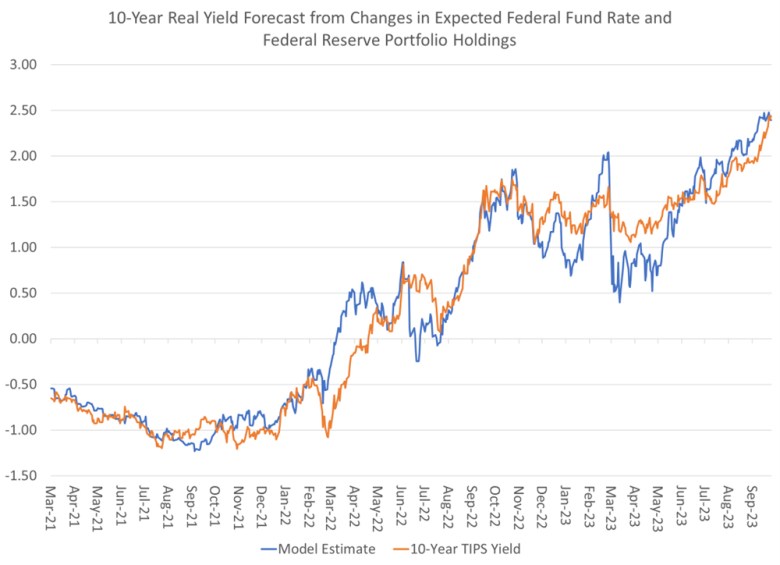

A simple regression model explains the yield on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities with just two factors, namely the expected Federal Reserve overnight, or federal funds rate, in two years (derived from futures markets) and the size of the Federal Reserve’s own securities portfolio. The Fed expanded its portfolio by $5 trillion during the Covid crisis, and has now begun to shrink it.

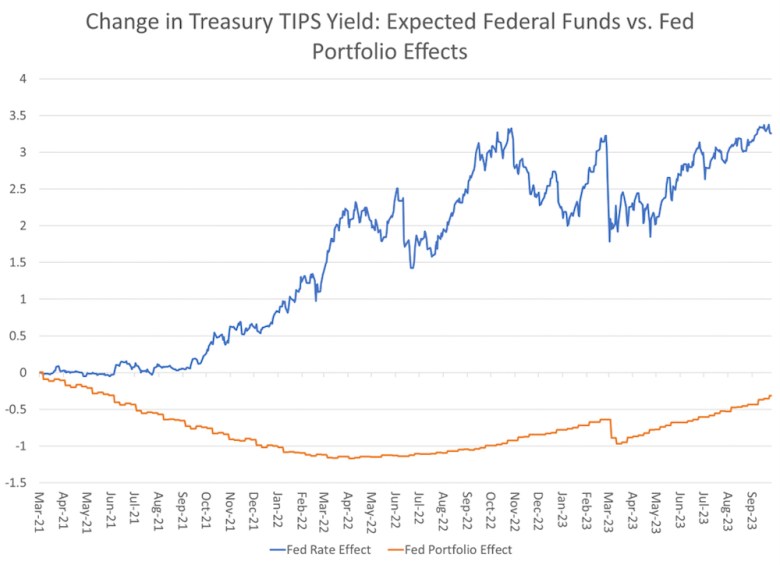

We then calculate the effect of the two predictive variables and show them separately on the chart below:

Remarkably, this analysis shows that expectations about future interest rate moves by the Fed haven’t had much impact on real or inflation-protected Treasury yields during the past year.

The effect of the expected federal funds rate on real yields peaked a year ago, in October 2022, at just below 3%. But the Fed Portfolio effect, which helped bring yields down between March 2021 and May 2022, explains nearly a full percentage point of the rise in real yields during the past year.

As the flood of Treasuries continues to rise, so will real US yields. The Federal Reserve may lose control of the long end of the yield curve, leading to a permanent burden on growth, rather like Italy today.

Follow David P Goldman on X, formerly Twitter, at @davidpgoldman