Britain needs to acknowledge rather than deny its weaknesses in goods trade, and leverage its strength in services • Resolution Foundation

The UK economy swiftly exited its recession in the first quarter of 2024 thanks in part to an improving trade balance. This is good news – but an improving trade balance is not the same as a successful trade performance. Indeed, GDP was boosted despite the UK’s total trade with the rest of the world falling, thanks to imports falling by more (2.6 per cent) than exports (which fell by just 0.5 per cent).[i]

Wonky trade data has been in the news a lot recently. The House of Commons debated UK trade performance in early May. In her opening comments, the Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch, asserted that “The latest trade data… should give everyone in this House cause for celebration and renewed pride in our country,” arguing that the post-Brexit trade performance of both goods and services was something to phone home about.

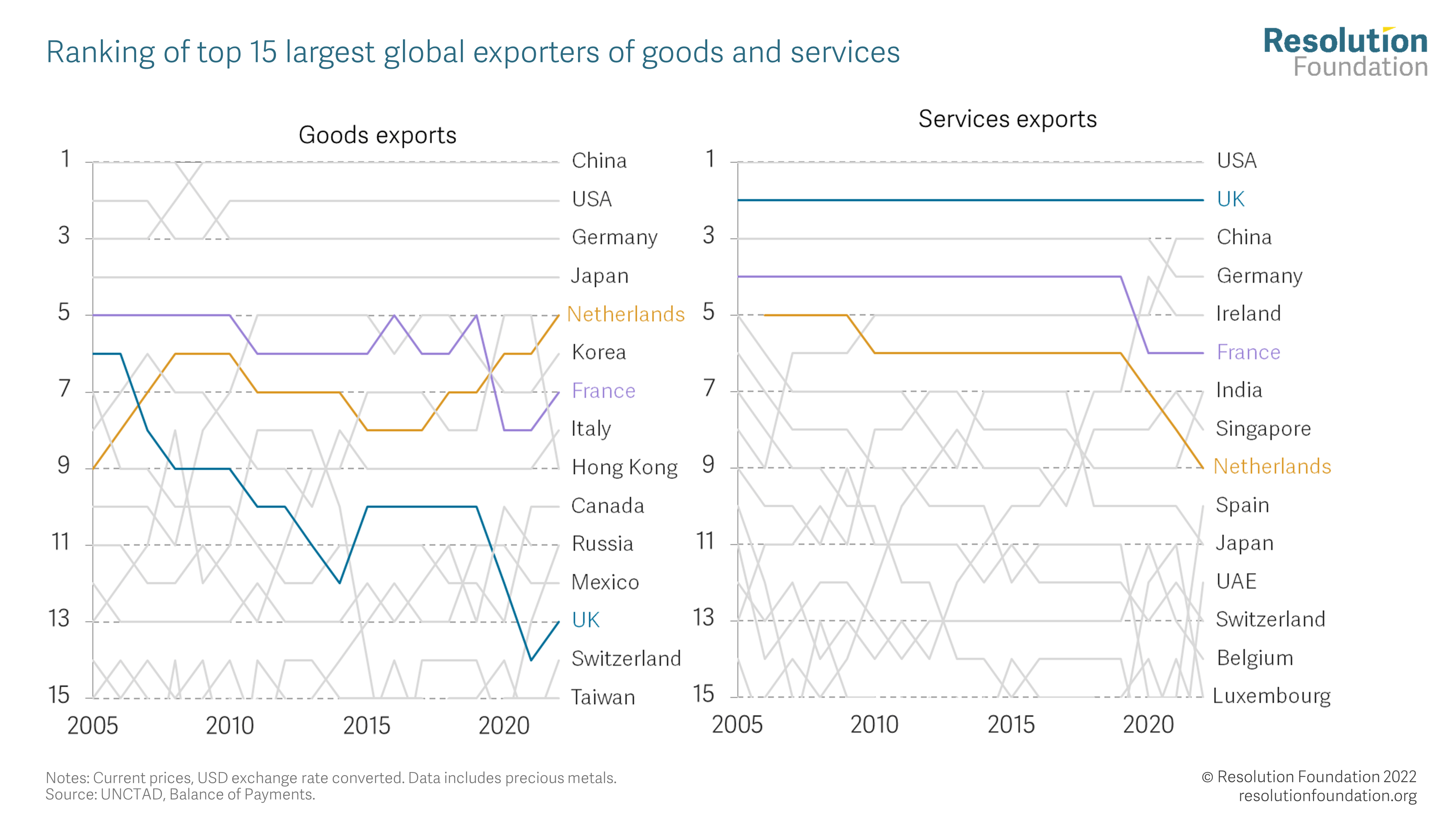

So, should we be celebrating the UK’s recent trade performance? Britain was the fourth largest exporter in the world in 2022 after all. But, the general story of strong UK exports in 2022 becomes unstuck when you consider the different performances of services and goods trade. In 2022, the UK can celebrate yet another year as the second largest services exporter, but we have fallen to thirteenth on the rankings of goods exporters.

Britain’s services exports are normal compared with our peers, but goods exports are wasting away

Some argue that the UK’s decline in goods exports is an inevitable result of ‘slowbalisation’. It’s certainly true that services trade has grown faster than goods in recent years – a trend that is expected to continue.

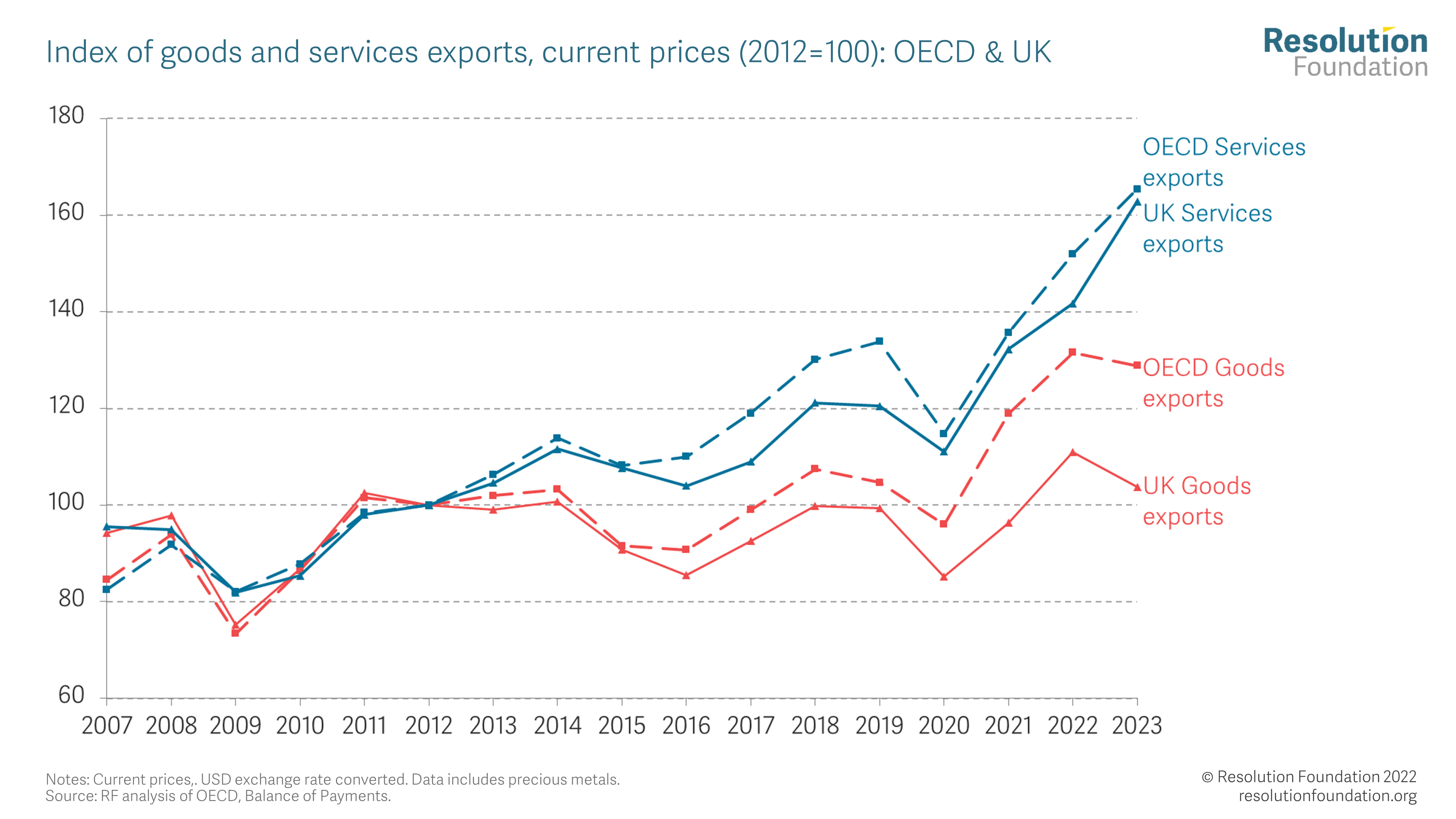

But the UK’s performance in goods trade, relative to similar economies, has been dismal. Since 2019, the UK’s goods exports have grown by just 4 per cent, compared with OECD countries’ goods exports growing 23 per cent. Further, this international data includes trade in precious metals which cause volatility without adding economic value (not only is this trade more akin to investing in stocks and shares, but it is actually GDP neutral). Excluding precious metals and the recent bout of inflation, the UK’s goods exports look even more bleak: they are now 17 per cent below 2019 levels, while goods imports are 14.9 per cent below. [ii] It is hard to see how this is a cause for celebration.

Britain’s goods predicament is in sharp contrast to the resilience of the UK’s services trade. The UK is one of the most services-oriented traders in the world. Services make up more than half of the UK’s exports, compared with 30 per cent for the US, and just 20 per cent for Germany. And Britain has maintained this international strength in services: the UK’s services exports (almost) kept pace with the OECD’s, growing 63 per cent since 2012. This is not just London’s bankers doing well – the UK’s financial services exports have been falling as a share of total services exports since the financial crisis – rather a diverse mix of lawyers, architects, advertisers and software engineers selling services overseas.

This recent decline in goods exports isn’t linked to a commensurate decline in hours worked

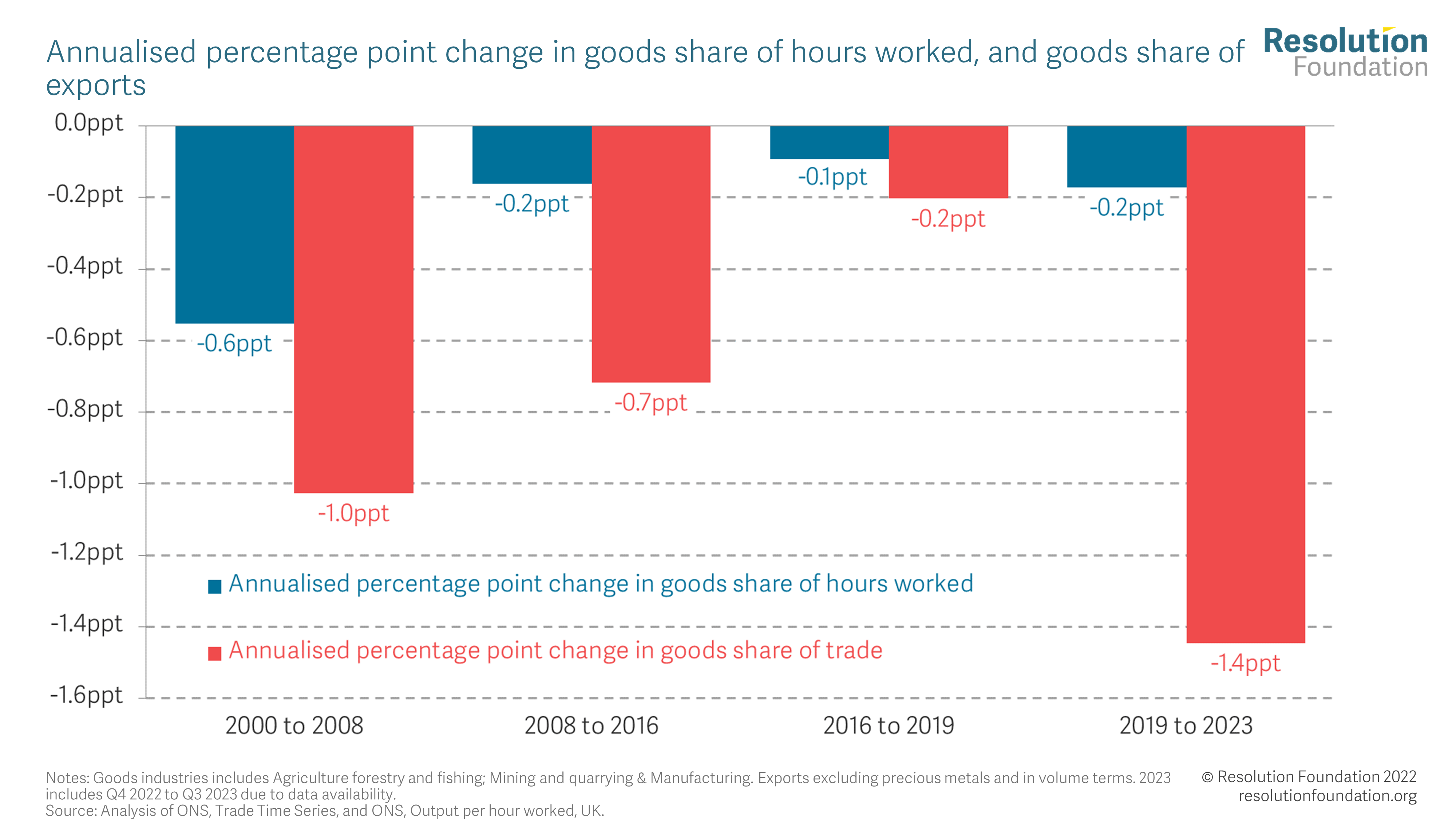

Of course, Britain’s transition from goods to services activities has been underway for many years. Goods industries now account for just 10 per cent of hours worked in the UK, falling from 18 per cent at the start of the millennium. It would follow that relatively fewer hours working to produce goods means that there are relatively fewer goods to sell overseas. For example, before the financial crisis, the goods share of hours fell by 0.6 percentage points each year, while the goods share of trade fell by 1.0 percentage points.

However, the recent decline in goods trade is far more pronounced relative to the fall in hours worked. Since 2019, the goods share of hours worked fell just 0.2 percentage points each year while the goods share of trade fell a sizable 1.4 percentage points annually. While there have been global shocks since 2019 – the pandemic and the European energy crisis to name a couple – the UK’s weak performance internationally combined with this fall in goods share of exports suggests that the UK’s weakness in goods can no longer be attributed to a general decline in the UK’s share of goods employment.

Acknowledging that all is not rosy on goods trade is the first step to addressing it – and this must include a straightforward conversation about reducing UK-EU trade frictions. But that conversation should also focus on leveraging the UK’s strengths in services. After all, this is where Britain’s future prosperity is likely to come from.

[i] Unless otherwise specified, figures in this blog which compare goods and services trade internationally are in current prices. Data are sourced from ONS, UK trade time series, May 2024.

[ii] It is important to note that the UK’s goods weakness isn’t driven by EU trade in particular. Indeed, in volume terms, the EU share of imports in Q1 2024 was 57 per cent, above its Q1 2019 levels of 55 per cent. Meanwhile the EU share of goods exports was 48 per cent, slightly below Q1 2019 levels of 51 per cent. The ONS notes that there is a discontinuity in trade data before and after 2021 affecting exports and imports with the EU due to a change in data collection methods for goods trade.