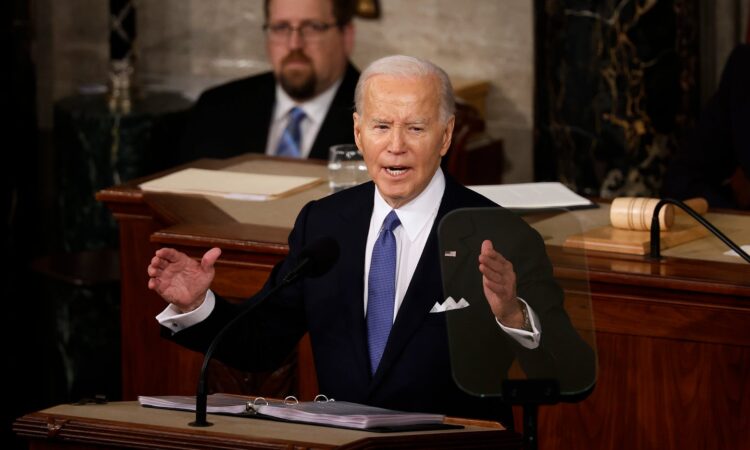

President Joe Biden spent most of his recent State of the Union address celebrating his economic record, with good reason. There is no denying the numbers: The United States currently enjoys the highest rate of economic growth among nations in the G7, the lowest inflation, and the strongest wage growth. The unemployment rate hasn’t been this low for this long in half a century. Even accounting for inflation, wages are higher today than they were before the coronavirus pandemic, and the biggest wage gains have accrued among the lowest-paid workers, resulting in a dramatic reduction in overall wage inequality. The economy is even outperforming among communities that are often excluded from boom-time gains. Biden has overseen the lowest Black unemployment rate on record and the lowest ever unemployment rate for workers with disabilities. The American economy isn’t perfect, but by any historical standard it is very, very good.

So, it’s remarkable that Biden finds himself needing to do so much persuasion on the campaign trail. Voter views on the economy are modestly improving, but survey after survey reveals a disconnect between the country’s economic performance and public sentiment. A recent USA Today poll shows that only one-third of voters believe that the economy is currently in “recovery.”

Economists and political messaging gurus have been trying to explain this for some time now, and while there are subtle differences among their various explanations, most ultimately argue that voters really, truly do not like inflation and are also a little confused when they talk about the economy.

There is surely something to both of these ideas—but there is a distinctly political tenor to Biden’s trouble on the economy that defies material conditions. Macroeconomic metrics have been improving steadily for a long time now—inflation peaked all the way back in the summer of 2022—and for much of that period, voter assessments of Biden’s performance actually deteriorated as the economy strengthened. Even today, when some voters say they like the economy, they remain reluctant to give Biden credit for it.

Much of this scenario can be laid at the feet of the Democratic Party. Not the official fundraising and administrative apparatus that runs conventions and formulates policy platforms, but the broad constellation of think tanks, nonprofits, academic experts, and journalists that collectively regulates the liberal intellectual atmosphere. For much of his presidency, Biden has been the victim of a centrist revolt against his economic program that the progressive wing of the party has been either unable or unwilling to put down. Everyone expects Republicans to give a Democratic president a hard time, but sharp and sustained economic criticism from Biden’s ostensible allies established a narrative of failure that has proved alarmingly resistant to reality.

Biden frequently draws distinctions between himself and the progressive left on police reform, immigration, and other issues where he thinks liberal ideas don’t fit the national mood. But this is not the way he has handled economic policy. From his first day in the Oval Office, Biden has embraced nearly every progressive criticism of Barack Obama’s approach to the economy, and translated those critiques into policy. Obama scoffed at labor unions; Biden walked a picket line and appointed the most pro-worker National Labor Relations Board in decades. Obama’s Education Department screwed over student debtors; Biden has canceled $138 billion in student debt. Obama defended big business; Biden has been an antitrust warrior. Obama was a free trader, while Biden subsidizes domestic manufacturing. Obama offered to cut Social Security; Biden just torched Republicans during his State of the Union for planning the same thing.

The list goes on. But the most important economic distinction between Biden and Obama is on crisis relief. The unemployment rate was high and rising when Obama entered office, escalating to 9 percent by April 2009, a level it would not retreat below for more than two years. When jobs did eventually return, most of those that were created paid poverty wages. The abysmal labor market made his presidency synonymous with the Great Recession.

The chief lesson Biden’s advisers took from this miserable experience was that the government didn’t spend enough in Obama’s 2009 stimulus package to get unemployment under control. More money would have meant more jobs, and more jobs would have put upward pressure on wages.

So Biden opted to spend much bigger out of the gate—$1.9 trillion to Obama’s $800 billion—and continued to secure additional rounds of support right up to the 2022 midterms. Obama began calling for budget cuts with unemployment still stuck above 9 percent, but Biden never pivoted to austerity, and ultimately secured well over $1 trillion in additional public investment after his initial stimulus bill had been enacted.

All this fiscal support resulted in a much stronger labor market. The unemployment rate fell below 5 percent by September 2021—a level Obama did not enjoy until the final days of his presidency—amid record wage growth for low-income workers. The economy never recovered all the manufacturing jobs it lost during the Wall Street crash. Biden had recovered all of those lost in the COVID collapse by May 2022. The COVID crash was sharper, deeper, and more physically disruptive to global trade than the 2008 Wall Street meltdown was, but the U.S. economy rebounded faster, stronger, and more equitably thanks to Biden’s more aggressive relief effort.

But not everyone was happy about this strategy at the time. When Biden signed his first economic relief bill into law in March 2021, former Obama adviser Larry Summers declared it “the least responsible macroeconomic policy we’ve had in the last 40 years” and upbraided “the Democratic left” for preventing a smaller package. All this spending, Summers claimed, risked a run of inflation. People were going to have too much money on their hands, and this excess spending power would lead to higher prices that made everyone poorer. When prices did indeed begin rising in the second half of 2021, the business press hailed Summers as a prophet, and a host of liberal commentators began tipping their hats to him.

Inflation arrived when the national mood was already in the toilet. Deadly car accidents were up, road rage incidents were soaring, and murder rates were rising. More people died from COVID-19 in 2021 than in 2020, even though vaccines were widely available. In monthly Gallup polling, Biden’s approval rating fell from 56 percent in June 2021 to 40 percent in January 2022, and all of this negativity made progressive institutions increasingly reluctant to claim credit for his approach to economic relief. Voters didn’t seem to care about Biden’s strong labor market—they were mad about inflation and everything else.

And so the economic commentary field remained open to Summers and other expert doomsayers—including some with politics well to Summers’ left. Economics dominated the news cycle in a way that it hadn’t since the banking crash, and seemingly everyone had something terrible to say about it. Biden wasn’t creating enough union jobs. His spending was really just a corporate welfare extravaganza. He was stealing jobs from Europe. There were too many regulations on manufacturers. There weren’t enough regulations on manufacturers. A recession was coming. A recession was already here. Some high-profile Democrats even insisted that a recession was necessary—on CNBC, former Obama and Clinton adviser Jason Furman argued that millions of workers would have to be laid off to get inflation back under control. Summers even floated the possibility of 10 percent unemployment.

To give all these haters their due, it really is hard to understand what is happening in the economy in real time, and even the best economists sometimes make predictions that look silly in retrospect. But what is remarkable about the Biden era is the degree to which critics on the left, right, and center basically agreed with one another beneath all the ideological dross. Almost everyone had come up with a way to argue that Biden had engaged in wasteful spending that left ordinary people behind.

Almost everyone. Throughout all this ugliness, a niche discourse continued in the econosphere about whether Summers had correctly nailed the cause of inflation. If Americans really were victims of overspending, then the only way to get inflation back down would indeed be to cause a recession. The problem, according to Summers and Furman, was that everyone had too much money. The solution was to take that money away.

But another camp argued that this was the wrong way to look at an economy that had just emerged from a massive shock like the COVID-19 pandemic. In this telling, inflation was driven not so much by an excess of consumer demand as by a dearth of product supply. It was a lot harder to make and distribute a whole host of goods when businesses around the world kept shutting down, and even once everything had fully reopened, it took a long time for companies to reestablish sources and connections. If supply shortages were indeed responsible for higher prices, then Biden’s spending was a feature, not a bug—it was the only thing standing between American households and the economic abyss.

Many economic disputes are vague enough to allow for essentially endless ideological stalemate over statistics, but in this case, a straightforward real-world test was available. Summers and Furman were arguing that layoffs were the only way to bring inflation down. If inflation fell without a flood of layoffs, then the rest of their diagnosis would have to fall with it.

In the American economy, policymakers typically induce job losses through the Federal Reserve. When the Fed raises interest rates, it’s trying to tamp down inflation by creating job losses: Higher rates mean higher business costs, and businesses lay people off in order to remain profitable. This was the Fed’s strategy when it began hiking rates in spring 2022.

The layoffs, however, refused to materialize. When inflation peaked at 9.1 percent in June 2022, the unemployment rate stood at 3.6 percent. Today, using the same metrics, inflation is just 3.2 percent, and unemployment is at just 3.9 percent. For 12 of the previous 19 months, the jobless rate has held steady at or below its June 2022 level, while inflation has been running below 4 percent since June 2023. Economists are still debating why the Fed’s higher rates didn’t translate into job losses, but the important point is that millions of people were not, in fact, fired. Moreover, millions of people did not need to be fired in order to fix inflation. As Mike Konczal concluded in a report for the Roosevelt Institute in September 2023, the vast majority of inflation during the Biden years was driven by pandemic-related supply problems. Whatever was going wrong in 2022, it wasn’t because you were too rich.

There is some evidence that the economic commentariat is coming to its senses as the 2024 election approaches. Some of the same centrists who ripped Biden’s stimulus package in 2021 are now applauding his recovery. The anti-Biden left has largely abandoned the economic playing field, finding cleaner grounds for criticism on other subjects. Contrary to the narrative abuse directed at Biden over the past few years, the economic numbers across his presidency tell a simple, optimistic story about the art of government in the democratic world. The American economy is strong today for the same reason that the labor market has been strong throughout Biden’s presidency: the U.S. government spent a ton of money to support workers and their families. Biden has not only established a blueprint for successful crisis management, but he has achieved something on the economy that pessimists across the ideological spectrum have been declaring impossible for much of the 21st century: He learned from the government’s prior mistakes and found a way to govern better.