The Idea – a New Threat Calls for U.S. Leadership, New Policy Tools

Economically coercive acts by adversaries create opportunities for the United States to demonstrate its leadership in the world, a means to showcase our commitment to existing partners, and provide a foundation for economic engagement with new partners. Malign actors have strengthened demand among countries of the Indo-Pacific region and beyond for a robust U.S. economic presence by intimidating neighbors and threatening trading partners. Economic coercion is using economic means to achieve specific political ends. By offering support and countervailing opportunities to partners in their times of need the U.S. government can bolster our international relationships and deter future coercion, thus enhancing our security, prosperity, alliances, and political standing. The Government of Japan is also considering policy options to meet this challenge and could be a valuable partner, along other G7 members, the EU, and Australia.

Economic coercion is, simply put, fighting a battle with economic tools on behalf of political objectives. The United States has an interest in countering such economic coercion by offering collective pushback through extension of support to targeted countries appropriate to the specific circumstances. To do so, we must update our policy toolkit to clarify authorities to support foreign partners. A swift short-term response by government could ameliorate economic stress while the private sector adjusts to finding new export markets or attracting new investors. Failure to act leaves countries, particularly those with small economies and fragile political systems, vulnerable to increased economic coercion.

A Growing Challenge

The coercive dimension of PRC economic statecraft has taken different forms and targeted various countries – in the Indo-Pacific and including a large number of European countries – for over a decade, and Russia has shown during its war against Ukraine that it is following a similar playbook when it deployed its energy resources against Europe. America’s leadership in Europe’s time of need helped it prevail against Russia. These lessons learned can be applied against China. Collective unified action led by the United States can aid allies when facing political and economic pressure.

All cases of economic coercion share the feature of imposition of economic hardship on countries for a political purpose, particularly changing those countries’ current behavior and deterring other trading partners from making similar choices in the future. In a detailed 2018 paper, Peter Harrell described economic coercion by the PRC as “one of the most prominent and significant security and economic aspects of the present great-power competition.” Matthew Goodman in a 2022 paper summarized the key characteristics of Beijing’s approach as “informality, ingenuity, targeting politically sensitive sectors, and, in many cases, ineffectiveness.”

A February 2023 paper by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) and a March 2023 paper by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) independently detail studies of cases of the PRC’s economic coercion. The evidence is clear. The policy tools vary. The current international response is lacking.

While acts of coercion – such as China’s 2019 bullying the National Basketball Association (NBA) into retracting a tweet appearing in support of Hong Kong democracy from an NBA general manager, by withdrawing billions of dollars of merchandise goods and halting game broadcasts – attracted broad media attention. Countless other coercive acts are likely happening without public awareness. An earlier September 2020 ASPI report listed almost two dozen cases from 2010 to 2020. Similarly, in a December 2021 statement to the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, Bonnie Glaser of the German Marshall Fund listed 14 cases of PRC trade coercion from 2010 through 2021. Make no mistake, there are many examples of hard and soft economic coercion. Set out below are prominent examples of economic coercion in response to a political stance by the country targeted. While there are distinct patterns to China’s economic coercion playbook, there are also distinct lessons on how to push back to win.

Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s depiction of countries economically coerced by the PRC

Source: ASPI.org

Prominent Cases of Economic Coercion

Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan

– New York Times, September 22, 2010

Japanese Maritime Dispute, 2010-2012: In response to a collision involving boats of the two countries near the Senkaku Islands in 2010, the PRC restricted exports to Japan of rare earth elements (a category of metals within the larger critical minerals family). At the time China controlled 97% of rare earth oxide production and a significant share of processing capability.

- Japan’s government estimated it spent $1 billion on mitigation and diversification.

- With the United States and EU, Japan filed a WTO case against China and won in 2014.

- While China did not succeed in blocking rare earth exports, Japan did release the Chinese captain of the fishing boat. By 2020, Japan had reduced its reliance on rare earths imported from China from over 90% to 58%.

The Senkaku Islands, which are claimed by Japan and China (Asahi Shimbun file photo)

Philippines feels the economic cost of standing up to China

– Christian Science Monitor, May 15, 2012

Philippines Maritime Dispute, 2012-2016: After a 2012 confrontation between Manila and Beijing over the disputed Scarborough Shoals in the South China Sea, the PRC quarantined fruit exports from the Philippines. The PRC government also encouraged tour operators to “suspend” all Philippine-bound tour groups and sent vessels to “protect” Chinese fishermen and block Filipino fishing boats.

- At the start of the dispute in 2012, the PRC was the third largest market for Philippine bananas (Japan was first), accounting for 14% of exports. The PRC also ranked fourth in foreign tourist arrivals, behind the ROK, the United States, and Japan.

- The Philippines brought the dispute to international arbitration, against PRC wishes, and in 2016 the Arbitral Tribunal decision in the case held that China violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

- The PRC blocked banana imports near decision points by the international body. There is no consensus on the economic impact of the dispute, but the perception of another country targeting key sectors (banana and tourism) made for a striking public impact.

- The campaign ended when then President Rodrigo Duterte proved more amenable to PRC demands. The Nikkei reported in 2018 that China surpassed Japan as the top destination for Philippine bananas, buying $496 million worth, up 71% from 2017, while orders from Japan rose 24% to $485 million, according to Philippine government data.

- Since 2016 the PRC has invested in infrastructure near Davao (a banana producing region and Duterte’s home island) and Japan has pursued metro Manila rail projects.

China destroys 35 tons of “substandard bananas” from the Philippines (Source: Global Times)

Angered by U.S. anti-missile system, China takes economic revenge

– CBS News, April 7, 2017

ROK THAAD Missile Deployment, 2016-2017: After Seoul decided to deploy U.S. THAAD missile systems in 2016, Beijing orchestrated boycotts by Chinese consumers and tourists traveling to the Republic of Korea, with an estimated impact of cutting the country’s GDP by 0.4 percent in 2017. This was the largest case of coercion of a major economy and U.S. ally.

- Center for a New American Security (CNAS) summarized PRC coercive actions: curbing tourism; cutting imports of cultural products such as cosmetics and popular music; and targeting auto companies. The PRC also used regulatory measures, including alleged fire code violations, to close almost 90 Korean-owned Lotte Mart stores in China.

- Lotte, which provided land for hosting THAAD, reportedly lost over $1.7 billion following its exit from the PRC supermarket business. Hyundai Research Institute estimated the tourism reduction cost the ROK approximately $15.6 billion in lost revenue across the ROK. Hyundai and Kia reported 30% lower sales in the PRC year on year in 2017.

- Notably, the PRC did not target ROK semiconductors, on which its economy relies, as that would have hurt both suppliers and end-users. Exports from the ROK to the PRC in this sector increased 2016, fueling an overall increase in exports to the PRC in 2017.

- The ROK chose not to file a WTO dispute, reportedly believing it had insufficient evidence of a coercive campaign due to the “informal” nature of the coercive acts.

- In October 2017, Seoul issued a “three no’s” principle to assure the PRC it would not expand the THAAD’s scope, and Beijing relented. The current Yoon Administration subsequently made clear this 2017 principle was no longer ROK policy.

Thermal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD). Photo: Lockheed Martin

Bristling at calls for coronavirus inquiry, China cuts Australian beef imports

– Washington Post, May 12, 2020

Dispute with Australia over COVID, 2020 to Present: In response to Australia’s call to conduct an independent inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 PRC officials disrupted Australian exports of coal, barley, beef, copper, wheat, and a range of other products.

- Since the ban, Australian exporters developed new markets. PRC pressure may also be easing, with January 2023 reports that Guangdong is processing Australian coal cargoes.

- Throughout the dispute, PRC imports of iron ore, LNG and wool remained largely unaffected, presumably due to a lack of alternative supply. In 2020, 66% of PRC iron ore imports came from Australia, whereas 88% of Australian exports went to the PRC.

- Since January 2022, limited shipments of Australian coal and lobsters have received PRC customs import permission.

Lithuania says China has told multinationals to boycott Vilnius over Taiwan row

– The Independent (UK), December 9, 2021

Lithuania, 2021-Present: Following Vilnius’s decision to allow the opening of a “Taiwanese Representative Office” in 2021, Beijing blocked imports and exports to Lithuania. It has also imposed informal secondary sanctions on goods exported to the PRC by other EU countries with Lithuania-made components (e.g., German automobiles with Lithuania-made sensors).

- Initial estimates indicated the impact of coercive acts was up to 0.5% reduction in Lithuanian GDP in 2022 even though that of the initial direct embargo was small.

- The European Union filed a WTO complaint in January 2022 accusing the PRC of discriminatory trade practices that threaten the integrity of the EU single market. The United States, the UK, Australia, among others, requested to be included in the case.

- Partners also responded with significant financial assistance. The EU approved 130 million euro support package for firms affected by PRC action. The United States approved a $600 million export credit facility in November 2021. Taiwan established a $200 million investment fund for Lithuanian industries (later expanded to other Eastern European countries) and a $1 billion fund for bilateral joint ventures. Both the United States and Taiwan also expedited approval for some agricultural exports from Lithuania.

Hard vs. Soft Coercion

The case studies detailed above serve as examples of the PRC’s most assertive, hard coercion. Below the surface, however, lie countless examples of soft coercion. That is, the PRC using its economic influence and market size to extract concessions from businesses and countries leery of losing access to the Chinese market or countries too small to resist the pressure. The smaller economies in the Indo-Pacific region are particularly vulnerable to the PRC’s economic coercion – one of the reasons they are eager for greater U.S. economic integration in the region. They are most dependent on trade with China – since China is already the largest and fastest growing trade partner – and they lack the economic flexibility and strength to wait four years for a WTO case to resolve the issue, as Japan did in 2014. By not having a clear strategic set of tools to respond, the United States not only loses economically, but also loses a political window of alliance building. Coming to the direct aid of a targeted, vulnerable country would win and endear the United States to a friend.

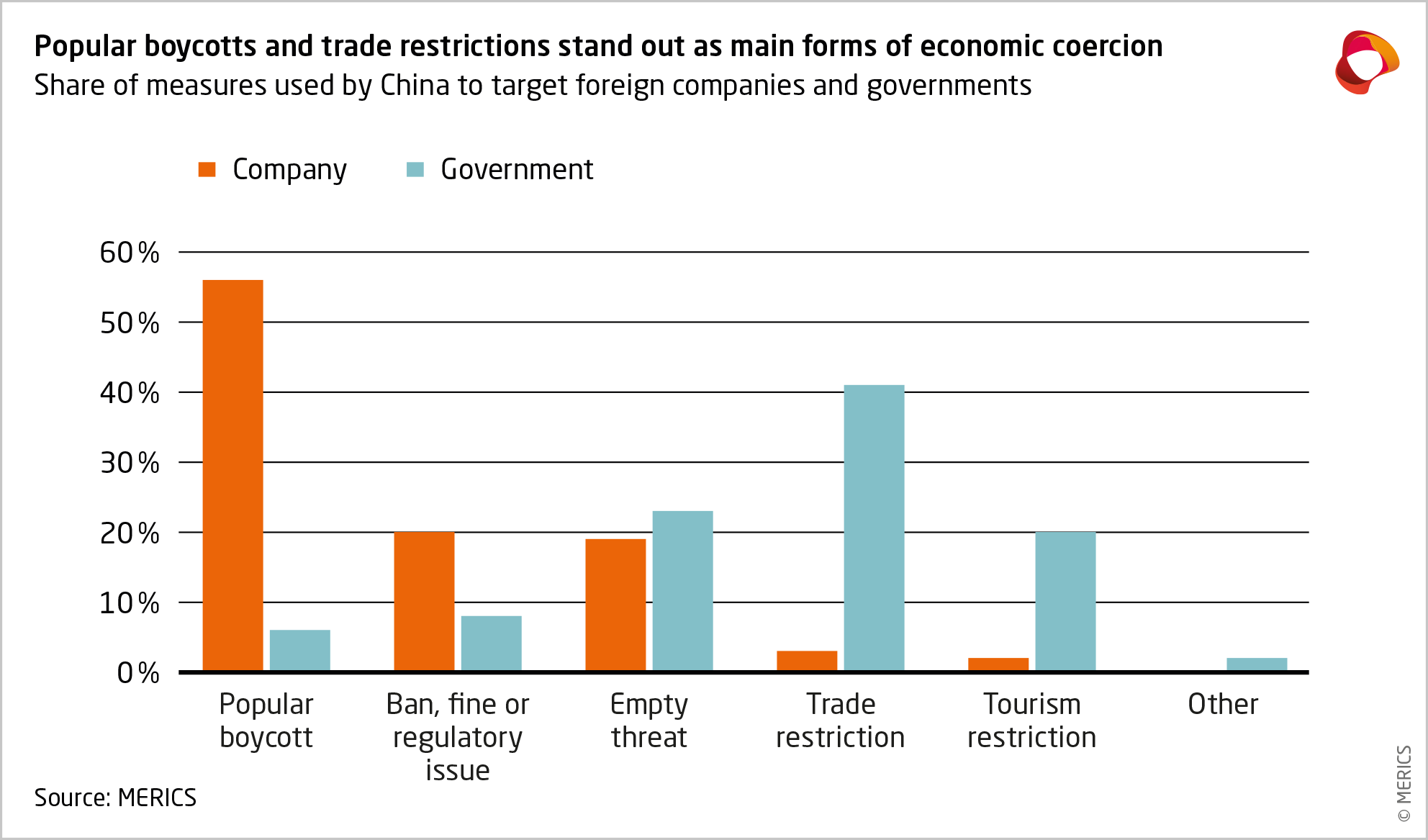

Multinational corporations also find themselves victims of the PRC’s soft coercion, and the size of the Chinese market and dependence on manufacturing in China can make the pressure particularly acute. Many U.S. based multinational corporations have been the target of soft coercion and have, in many cases, succumbed. Businesses, regardless of national affiliation, have strong incentives to comply with pressure to share IP or comply with other demands – and to remain silent about those demands – because running afoul of the PRC can lead to blacklisting. A Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) report estimated about one fifth of all cases of economic coercion it tracked were “empty threats,” that “may work to deter other governments and companies from unwanted action.” Popular boycotts (e.g., of the NBA following a tweet in support of Hong Kong democracy protestors) and exercising administrative discretion (e.g., problems in customs processing) are other examples of soft coercion.

Conclusion

The PRC’s economic toolbox contains a variety of coercive measures. Researchers have identified repeated use of various economic tools used by the PRC to elicit particular outcomes, such as: trade restrictions; investment restrictions; tourism restrictions; boycotts; state threats; and IP theft. Additional aggressive tactics include detention and cyberattacks.

EU backs Lithuania’s plan to aid firms amid China’s embargo

– Politico, April 26, 2022

We need a policy response to engage and win this battle. Examining the cases of countries successfully resisting economic coercion, such as Japan and Australia, reveals important patterns. Collective groupings, like the G7 or existing trade agreements, help countries resist China and survive the economic consequences. It is only too clear how reliance on one single partner to source or sell goods can wreak havoc should that partner’s own economic or political objective change or turn against one. Just look at Europe’s reliance on Russia for energy sources and the Philippine’s dependence on PRC banana purchases.

U.S. to boost natural gas deliveries to help wean Europe off Russian energy

– CBS News, March 25, 2022

New legislation could enable a rapid government response until private sector action can adjust. The European Union is also considering the adoption of an anti-coercion instrument which focuses on both deterrence and allows for retaliatory policies. The United States has various relief tools, such as export credit lines or expedited licensing at its disposal, and should not hesitate to use these until the private sector can reorient its business, as shown in the Japan and Australia examples. By working with our coalition partners to quickly support victims, we can demonstrate the value of a rules-based order and U.S. leadership. Presently, the WTO dispute resolution system is too time consuming for vulnerable countries. Therefore, the bureaucratic structure undermines rather than reinforces a rules-based system. It is clear that an effective response to the PRC’s coercion must be collective and must be led by the United States.

China begins to unwind ban on Australian coal imports

– Economist Intelligence Unit, January 11, 2023