- By Sam Francis & Faisal Islam, BBC Economics editor

- BBC News

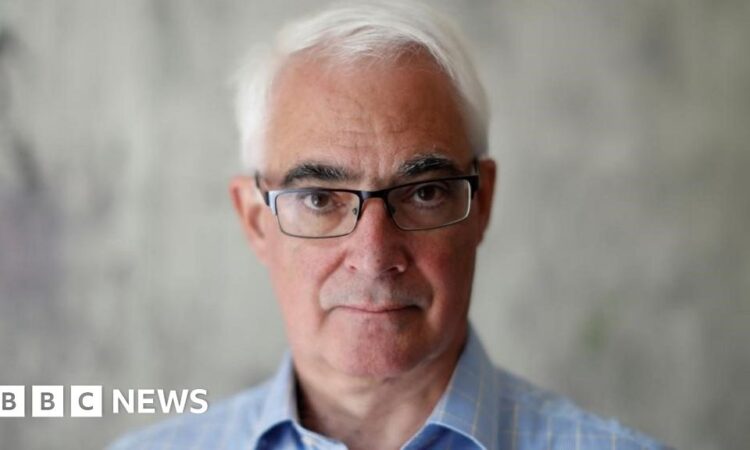

As a radical student, Alistair Darling hoped to reshape the world.

As chancellor, he found himself at the centre of global crisis steering the UK’s troubled banks back from the brink during the 2008 financial crash.

He served at the heart of New Labour, with 13 years in Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s cabinets.

He once said he hoped to be remembered as “the minister who began to eradicate poverty”, but he will go down in history for the actions he took as chancellor in 2008.

His were the steady pair of hands who shepherded the British economy through the near collapse of half its banking system. He was best known for having to nationalise Northern Rock at first, and then effectively the bulk of British banking amid runs on banks by the public and financial markets.

Alistair Darling tells of Gordon Brown’s time as prime minister in his new book

He began his memoir of his period at Number 11 with the phrase “I don’t believe in panicking until it’s absolutely necessary”.

It was a doctrine that was sorely tested as faced financial chaos unseen in Britain for decades.

Born in London, Alistair Darling attended the fee-paying Loretto School near Edinburgh. He did his legal training in the city before representing it in local government and ultimately in Parliament.

While Mr Darling had the air of a mild-mannered, non-confrontational Scottish lawyer, his political origins were actually somewhat more lively.

As a student activist in Aberdeen, he was associated with far-left policies and reportedly distributed “Marxist” leaflets at railway stations.

But after being elected as an MP in 1987, he left left-wing roots behind and his image was transformed from firebrand to moderate. Mr Darling became closely linked with efforts to modernise Labour.

Alistair Darling was elected to Parliament in 1987

In opposition, he served on the front bench in several roles, including as home affairs spokesman.

Ahead of the 1997 election, he also toured the boardrooms of the big City firms, to reassure them of New Labour’s intentions.

Following the party’s landslide election win, Mr Darling served as chief secretary to the Treasury, putting in place wide-ranging reforms to financial regulation.

He then replaced Harriet Harman as social security secretary – later re-named work and pensions secretary – delivering Labour’s welfare reforms and taking responsibility for spending a third of the government’s budget.

Mr Darling said he would like to be remembered as “the minister who began to eradicate poverty”, but he was targeted by pensioners outraged when their pensions were raised by only 75p.

The episode led to a rebellion at Labour’s conference in 2000, opposition coming from Labour giant Barbara Castle.

Mr Darling, said to have a knack for mastering complex briefs in record time, was parachuted into another “trouble” job in 2002, when Stephen Byers resigned as transport secretary amid the collapse of Railtrack.

EU referendum: Alistair Darling denies ‘Project Fear’

When his long-time political ally, Gordon Brown, moved to 10 Downing Street in June 2007, Mr Darling, the quiet man of the cabinet, replaced him as chancellor.

Many thought he would be a “yes” man, cowering in the shadow of his powerful boss.

But he staked out his independence when, in the summer of 2008 – and not long before the collapse of Lehman Brothers – he warned of the worst financial crisis in 60 years.

This resulted in a backlash from those close to Gordon Brown, with Mr Darling later remarking that the “forces of hell” had been unleashed on him.

And he fell out with his neighbour and boss over the need for spending cuts after the significant increase in government borrowing during the financial crisis.

That disagreement, Lord Darling believes, was what led to Labour’s 2010 general election defeat.

During the brief interregnum after the 2010 election, on a journey to Brussels, he privately acknowledged the game was up, and expressed little surprise at the Liberal Democrats handling David Cameron a stable five year majority.

After Labour lost power, Alistair Darling returned to the backbenches. But he took a central role in the Better Together campaign, which campaigned for a “No” vote in the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence.

He made a significant contribution although he reluctantly took on the role, and felt bruised by the schisms in Scottish society during a brutal campaign. But he joined back up with Gordon Brown, and ultimately played a vital role in keeping the union together.

He was created Lord Darling of Roulanish, in 2015 but retired from the House of Lords in 2020. He was married to Margaret, and had two children, Calum and Anna.