There has been a lot of talk in recent years about the need for a Just Transition to a dynamic green economy in the Northeast. The International Trade Union Confederation defines ‘Just Transition’ as ‘securing the future and livelihoods of workers and their communities in the transition to a low-carbon economy’.

But what exactly would that mean for the people of the region?

What might we be able to learn from our history, that could help to make a Just Transition really work, and how do we build the power necessary to achieving it?

There is much we can learn from our heritage in the Northeast. In the 19th century, people came into the region, from other parts of Northern England, from Cornwall, from Scotland and from Ireland. Despite their differences, they were able to build strong and cohesive communities. Part of the reason for this, was that people came together around common enterprises, be it mines, or shipyards or iron and steel works.

Clearly the common enterprises that people were involved in, helped to bring people from disparate backgrounds together. When working down a mine, a pitman who was reliant for his life on his workmate or marra, was not usually going to be too bothered about where they came from or what religion they were. And while there was friction between communities and others, these were on a generally smaller scale than others of the country. Instead as the 19th century wore on, people in the Northeast worked together more closely in several ways, to raise their collective quality of life.

Carbon free economy

As we move forward into a greener future, with a Just Transition to a carbon-free economy we again need to find ways of bringing people together around common enterprises. We live in a much more fragmented society, without the large industrial common enterprises that helped to bring people together in the 19th century. However, there are still many common enterprises that can bring people together, limit social exclusion and help to bring about a fair transition to a carbon-free economy that benefits us all.

These can include health, especially after the experience of the Covid-19 pandemic, education and not least the environment. If we can see the transition to a green economy as the kind of common enterprise that the mine or the shipyard used to be, then that will surely help to make the transition both fairer and more effective.

Mining heritage and ‘community spirit’

Indeed, when thinking about what a Just Transition in the Northeast might look like, we can take a lot of inspiration from the past, if we think of the mining heritage as having three components. There was the mining itself and we know that we need to leave fossil fuels in the ground and move on to renewable, clean energy. However, there are two aspects of the mining heritage which we can, and I believe we must, take forward with us into the future.

The first of these is the ‘community spirit’, which helped to bring people together around the common economic enterprises mentioned earlier. A greater sense of community, the kind that was seen in the Cooperative movement of the second half of the 19th century is needed now. Indeed, we have much to learn from the growth of the Cooperative movement in the Northeast as we move towards a Just Transition, which might see the development of local green energy cooperatives.

Rise of the Cooperative movement

The modern Cooperative movement arguably began in Rochdale, and it wasn’t for another 15 years, until Joseph Cowen’s reading for Holyoake at the Blaydon Mechanics’ Institute in 1859, that the Northeast really became heavily involved in developing cooperatives. After that, however, there was an explosion in cooperatives and by the end of the 19th century, there were more cooperative members in our region than anywhere else in the country.

Helping this explosion was the beneficial influence of 1852 Provident Societies Act and, in our time, friendly legislation will be important in helping us to build a Just Transition. This was allied to the enthusiasm of early cooperators, a quality we will need as we move to towards a transition to a carbon-free economy.

It is also notable that there were both moral and practical reasons for cooperatives being developed, a reminder to us all that what is the right thing to do can also be the practical thing to do. Indeed, the early Cooperative movement was known for its flexibility and adaptability, two more qualities we will need in the coming years to develop the Just Transition. Also notable in the Cooperative movement of the 19th century was the regional leadership of Joseph Cowen; perhaps the new NE Northeast Mayor could fill this role for us. Finally, it is important to note that publications such as Cooperator developing a culture of cooperation across the country and media will have to play a similar role in any Just Transition in the Northeast.

Spirit of innovation

The second of the aspects of the mining heritage, which we will need in the future is the spirit of innovation. The coal industry helped to cause a remarkable period of technological innovation in the Northeast, with a truly remarkable number of world-changing inventions coming from the region. These include the railways, the mining safety lamp, the hydraulic crane, the light bulb, the light switch and the first turbines in the world capable of lighting up a city and the first turbine -driven ship, the Turbinia, among others.

We will need this spirit of innovation again, as we confront the Climate Crisis, and it is encouraging to see that the Northeast is still ahead of the game in some areas of technological change. For example, it was reported by Think Geo Energy that a new green energy project is underway in Gateshead, where “heat is extracted from mine water from 150 meters below the Gateshead town centre via three boreholes that have been drilled into 200-year-old mine workings.” This shows both that the spirit of innovation is alive and well in the region and that we can use our mining heritage to help build a greener future.

We have much to learn from our heritage. We were an energy producing superpower for centuries, with our coal mining, and could feasibly be an energy superpower again, with the development of new, green industries. While we must change the form of energy we produce, as an energy-producing region, we still need to keep the traditions of community and innovation. If we do so, then we can develop a truly inclusive and fair transition to a greener economy, based around the development of common enterprises.

‘Community spirit’ or solidarity has remained in the Northeast since early in its innovative and industrious history. From it, people have organised for people’s rights and in the words of Dr Martin Luther King in his speech given at Newcastle University in 1967, have regularly confronted the “…problem of racism, the problem of poverty, and the problem of war”.

Just Transition in the Northeast could address all three, especially now as we enter a new structure of devolved regional governance. But let’s keep in perspective what governance is and the role of what is known as ‘community power’. Because community power emerges from the spirit and solidarity of communities in the Northeast, in ensuring that government serves ‘the people’.

Community power and governance

Governance is about control: it’s about who has power and what they’re willing to do to keep it. It is usually administered from the top-down though its ‘constituencies’ have a role, mainly through voting. Its structure tends to be more rigid in form, but not always.

According to the independent think tank New Local, community power “is the belief that people should have a say over the places in which they live and the services they use”. Community power is about direct democracy in which publics have a more direct say in policies and regulations that affect them. Whereas community organising — where people come together to act on an issue of self-interest — is about championing positive social change by tapping into the relational power of communities.

Community power keeps governance in check especially when it is unjust. It tends to be from the bottom up and more fluid though there will be parts that are rigid and may even resemble governance itself. In the Northeast we have a lot of community power, it is ‘real’, but perhaps not always actualised in ways that it could be. Community power is fluid because it flows through masses of people and rarely sits still. In contrast hierarchical forms of power in governance are often more concentrated higher up the ladder.

Community power remoulds the rigidity of local governance in the Northeast and elsewhere.

Co-produced workshops

A series of three co-produced workshops facilitated by a PhD studentship at Newcastle University and Tyne & Wear Citizens that took place last summer: ‘Northeast Justice in Action: Listening, Networking, Acting for Social & Environmental Justice’, whose findings were outlined in ‘What could a Northeast Mayor do?

Part 2 housing and regeneration’, found that ‘community power’ can and does deliver in achieving justice for climate, housing, energy, transport, and food in the Northeast, and likely much more. The workshops were funded by the Newcastle University Social Justice Advisory Group.

Climate crisis

From a Just Transition perspective, to address the climate crisis, the current processes in place within and outside of local authorities to regulate and reduce greenhouse gas emissions are not enough. They are too technocratic for communities to have much of a voice in how ‘net-zero’ is delivered. Perhaps government intended for it to be this way when remaining mostly silent on the ‘the public’s’ contribution to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Incumbent politicians regardless of party affiliation can and should be challenged outright about climate change measures the Northeast could lead on, and publics could substantially contribute to. This includes insulation of existing housing infrastructure, some of which is privately owned by some of the country’s worst ‘slumlords’.

Let’s continue to grow community power not merely for our own sake but for those who will live 50-100+ years from now. This is why young people can and should have a greater say in local policy. If they oversaw climate change mitigation and adaptation, we probably wouldn’t be in this mess in terms of missing national net-zero targets. Let’s cut the technocratic jargon from climate change politics. The numbers matter, but only when communicated in meaningful ways — backed by tangible actions — do they make a difference.

Housing crisis

Runaway ‘landlordism’ is largely to blame for the country’s housing crisis and is really what ‘makes the poor poorer’. A ‘community first fair rental policy’, along with a Good Landlord Charter, could help resolve this by putting people before profits. It’s not a pipedream. Government passed legislation to ban estate agent fees for tenants in 2019, which were. These fees were unjust and unnecessary. Why not tackle the unregulated private housing market that drains the financial resources of local communities’ financial resources?

Even vast swathes of ‘social housing’ are run as if they were a private corporation, not because it’s better for the tenants, but because it is a more efficient way to harvest money from low-income households. Make no mistake about it, the selloff of social housing hurt Northeast communities and continues to fester like an open wound.

This is an immense challenge but communities in the Northeast can take it a step further if they organise more around it, and something the new Mayor should adhere to. Housing cooperatives could become a staple rather than a niche market if enough people stand up against the corruption of the present system. Rent strikes if organised properly are not out of the question and require political support.

Public participation in net-zero policy

While communities cannot be expected to deliver net-zero targets solely on their own, public policies for climate change mitigation at multiple scales could stand to benefit from being more inclusive. The ‘neo-liberal way’, if it can be called this, of relying primarily on private market forces s alone to deliver climate change targets, is not only naive but counterproductive. This is why harnessing community power is imperative to resolving the climate crisis, and for forging sustainable economic opportunities for a Just Transition in the Northeast.

The North of Tyne Citizens Assembly on climate change held in 2021 that brought together 50 members of the public, helped break new ground in infusing public recommendations for addressing the climate crisis into local government policy. However, there is little publicly available evidence on whether the recommendations were taken up by NTCA or local authorities, and if so, how? The new Northeast Mayoral Combined Authority must answer to and implement these citizen recommendations and encourage its member councils to do the same. Perhaps another assembly inclusive of local authority members south of the Tyne (Durham, Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland) should also be pursued. When it comes to climate change everyone’s voice deserves to be heard.

The UK is a world leader in large scale offshore wind power generation, why can’t it be for community energy? As noted at the start of this article, the Northeast is a region of innovation. In this region community energy could be far more widespread than it is today, but where are the innovative technologies, funding mechanisms, and policies to make them real? Private investment firms based down south understand the value of renewable energy assets up here. They buy up former moorlands in Northumberland ‘cheaper than chips’ to install massive solar farms that can and should be locally owned.

Do we need renewable energy power plants? Yes. Should we fall back and succumb to the whims of the highest bidder? No! Also, it usually makes more spatial sense to have solar power plants on empty building rooftops and brownfield land than green belt. Internal investment means little without the will of the people, something private developers and local authorities must be challenged on tooth and nail.

Desired positive outcomes on all these issues are more likely to be successful if we build community power across the region. We have it, the solidarity is there in our towns, villages, cities, and rural hinterlands. When there’s talk about Just Transitions for the Northeast, let’s not make it another hollow term that has little resonance with people. Instead, let’s connect it with the region’s rich history of industry, innovation, social justice, activism, and civil rights.

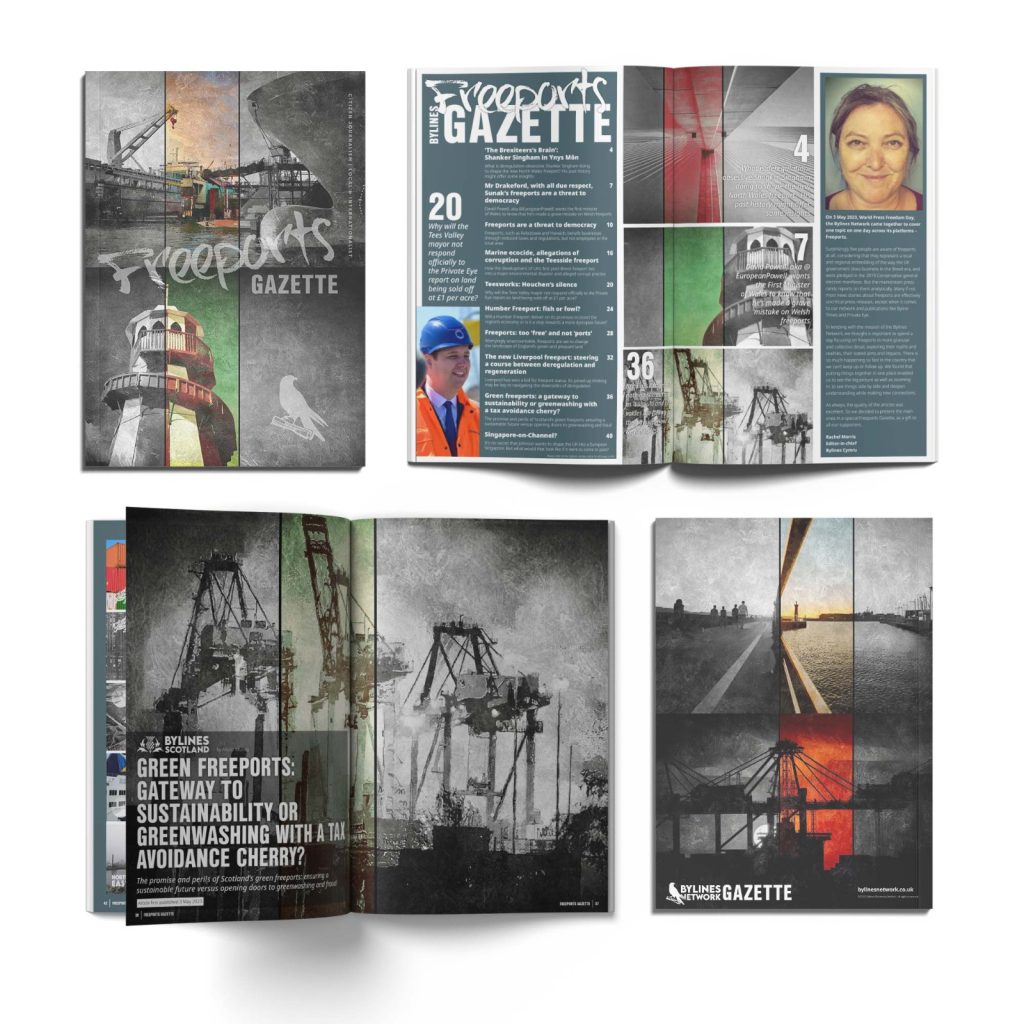

We publish a regular gazette that’s now available free to all our newsletter subscribers. Click on the image to access the Freeports Gazette edition and sign up to our mailing list via the button below!