Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The American economy is the envy of the Western world. Our nation’s economy grew at a nearly 5 percent annualized rate last quarter. The unemployment rate is hovering at historic lows. The percentage of prime-age Americans in the labor force is higher than it’s been since the 2008 financial crisis. Thanks to an abundance of employment opportunities, lower-income workers have recovered roughly 25 percent of the increase in wage inequality that accrued between Ronald Reagan’s election and Joe Biden’s. And wages have been rising faster than consumer prices for eight months now.

The European economy, by contrast, is stagnating. While American GDP is just barely below its pre-COVID trend, the EU’s is running 5 percent beneath its pre-pandemic trajectory. And yet, despite this slower growth, European consumers have been saddled with similar rates of inflation as their American counterparts.

Graphic: Financial Times

Thus, Joe Biden’s economic management looks objectively strong. The pandemic imposed real costs on economies throughout the West. Shutting down large swathes of the economy, and disrupting fragile supply chains, inevitably depressed nations’ productive capacity. Inflation was therefore unavoidable, unless governments chose to concentrate the costs of economic adjustment on the most vulnerable by tolerating a sustained period of elevated unemployment and poverty. Within the constraints imposed by a world-historic crisis, however, Biden guided the American economy to a superlative recovery. The U.S. has enjoyed stronger growth – at no greater cost to inflation — than Europe has. And as Martin Sandbu of the Financial Times writes, this divergence is largely attributable to America’s superior fiscal policy; which is to say, to Biden’s American Rescue Plan and the Trump-era COVID relief bills.

Nevertheless, the American public takes an extraordinarily dim view of the Biden economy. In a recent New York Times/Sienna College poll of 2024 battleground states, just 19 percent of voters described the economy as “good” or “excellent.” By a 59 percent to 37 percent margin, these battleground electorates disapproved of Biden’s economic record.

Those results are consistent with a Bloomberg/Morning Consult poll of seven swing states, which found that only 35 percent of voters trust Biden on the economy, with 51 percent saying that things were better under Donald Trump.

More direct gauges of economic satisfaction — untainted by a direct association with partisan politics — tell a similar story. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index has never returned to its pre-pandemic peak, and has fallen steadily for four straight months.

What explains the dissonance between the Biden economy’s objective virtues and the electorate’s overwhelming discontent? Many stalwart Democrats are inclined to blame the media, or the president’s inept messaging, or the inescapably bad “vibes” of a nation that still hasn’t recovered from the pandemic’s traumas.

It’s plausible that all of these factors have influenced the public’s dissatisfaction. But there are also several objective features of Biden-era economic life that could explain voters’ antipathy for the president. Here are three reasons why Americans are less than pleased with Bidenomics:

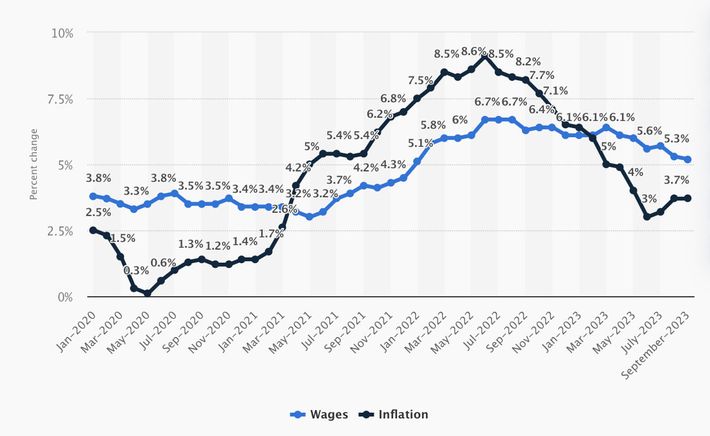

From one angle, the electorate’s antipathy for Biden’s economy doesn’t look all that hard to understand: Although real wages have been rising since February, the first two years of Biden’s presidency witnessed an exceptionally prolonged period in which consumer prices outpaced paycheck growth. In other words, for most of the Biden-era, U.S. workers’ purchasing power was falling.

Graphic: Statista

Again, this reversed in 2023. And the real hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers in the U.S. is now higher than it was before the pandemic.

But years of rapid inflation have nevertheless left the price level much higher than it was in 2019. In the long run, the nominal price of consumer goods should matter less than their price relative to wages. In 1950, a standard television cost $200. Today, one might pay closer to $500 for a TV of middling quality. Yet despite that higher sticker price, TVs are objectively much cheaper now, as they cost a much smaller share of the median worker’s earnings. But it’s been less than a year since inflation stopped outpacing wage growth. So, people still find the nominal prices on their grocery bills maddeningly high.

This reality is affirmed by a recent Blueprint/YouGov survey, which found that 64 percent of voters consider lower prices on “goods, services, and gas” to be their top priority, while only 7 percent said the same of “jobs.” The Biden administration’s economic message has understandably emphasized job creation, since its success on that front is unambiguous. Yet 15 percent of Americans are retired, and the vast majority of U.S. workers remained stably employed throughout the pandemic. So, the biggest beneficiaries of Biden-era job growth comprise a small fraction of the public, whereas all Americans are directly impacted by consumer prices.

The idea that Biden’s first two years in office poisoned his image as an economic manager is consistent with international political trends. As Matthew Yglesias has noted, nearly every head of state in a G-7 country has an abysmal approval rating. Biden’s 39 percent mark is actually slightly better than that of Justin Trudeau’s, which sits at 33 percent. In France, Emmanuel Macron’s approval is 26 percent; in Germany, Olaf Scholz’s is 25 percent; in Japan, Fumio Kishida’s in 22 percent. Tellingly, the only G-7 leader with significantly better marks than Biden is Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, who took power after the worst of the post-COVID inflation crisis, and is therefore not associated with it.

Americans’ incomes and savings aren’t set by wages alone. Another important determinant of households’ finances are government transfer payments. In 2021, the American Rescue Plan’s stimulus checks, expanded child tax credit, and enhanced unemployment benefits spurring a historic jump in Americans’ incomes and personal savings.

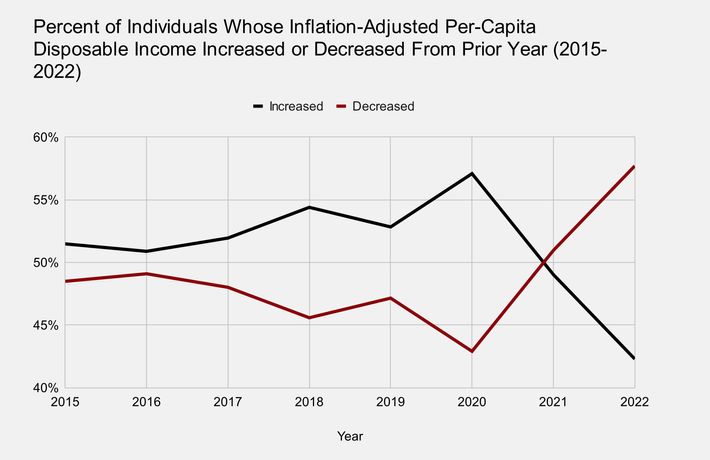

But since these programs were temporary, their impact dissipated over the next two years. As a result, Americans experienced a historically anomalous decline in their annual incomes and bank balances in 2022. As Matt Bruenig notes, in a typical year, about 45 percent of people enjoy less income than they did the year before. But in 2022, that share shot up to roughly 60 percent, as a result of both inflation and the fading out of pandemic-era transfer payments.

Photo: People’s Policy Project

Graphic: FRED

To be sure, Americans’ incomes are higher today than they were before the pandemic. And their balance sheets are also roughly as strong. It would not be perfectly rational for voters to be upset that their incomes declined merely because they received a 1,400 check in 2021 but not in 2022. Nevertheless, it’s plausible that the widespread experience of an income and savings drop has soured the national mood.

Finally, although inflation has cooled in 2023, interest rates have steadily risen to levels not seen in decades. And since a great deal of American consumer spending is financed through debt, higher borrowing costs limit the impact of price deceleration.

What’s more, the dissipation of households’ pandemic-era savings exacerbates the challenge posed by high interest rates. With no rainy-day fund to draw on, consumers have become increasingly dependent on credit cards for financing daily expenses. Credit card balances jumped 15 percent last quarter from one year earlier, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The average consumer balance is now at its highest point in 10 years.

Meanwhile, credit card rates have spiked by more than 5 percent since the Federal Reserve began hiking. As a result the credit card delinquency rate for American households has reached its highest point since the end of 2011.

At the same time, with mortgage rates hitting a two-decade high of 8 percent, many Americans feel that one of their core economic aspirations — home ownership — is now out of reach.

All of which is to say, voters’ disapproval of Biden’s economic management is plausibly rooted in objective conditions. But that isn’t necessarily bad news for the president. If inflation continues to moderate, then the Federal Reserve may cut interest rates next year, alleviating some of the pressure on consumers. At the same time, with each passing day, the post-COVID inflationary surge recedes further into the past. If the U.S. economy can continue on its current trajectory through Election Day, then voters may be more forgiving of Biden in November 2024 than they are today.