With the ascension of King Charles III to the British throne, some commentators have made much of the fact that the new stamp bearing his image features the king without a crown.

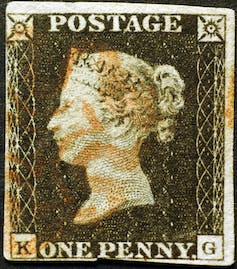

This is a major break with a tradition that began in 1840 with the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black, which featured the reigning monarch, Queen Victoria, wearing her crown.

Dave Bolton/iStock via Getty Images Plus

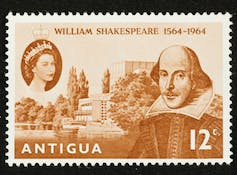

Less discussed is the fact that the living monarch’s image must appear on all British stamps because the monarch embodies the nation itself. This is true even for commemorative stamps that honor historically important persons and events. Whether sharing equal billing with another person or relegated to a corner, the living monarch’s image will always be found on British stamps.

DeAgostini Picture Library via Getty Images

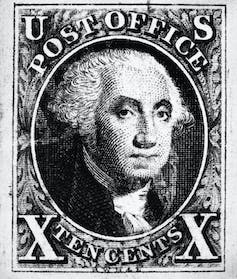

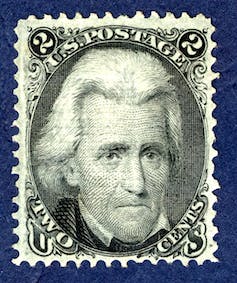

As we discuss in our recent book, “The American Stamp,” when the United States was ready to release its first stamps in 1847, the Post Office returned to the issues that had first been raised in a debate about coins. In 1792, when the U.S. mint was founded, a proposal to feature the heads of living presidents on the nation’s coinage was defeated in Congress by those who argued that to do so would be monarchical. In a republic, they proclaimed, only history, not heredity, could determine who was worthy of lending their likeness to the nation’s money.

It was agreed that only dead or allegorical persons – for example, the Goddess of Liberty – can be depicted on U.S. currencies. The postal service adopted similarly democratic ideals.

Bettmann via Getty Images

The questions of the day became “Who deserves to be honored on American stamps?” or “What does democracy look like?” The Post Office answered, “like dead heroes” – or, more specifically, like images of deceased white males whom history deemed central to the nation’s founding and growth. The country’s first stamp designs featured Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, who had died in the previous century.

Over the 176 years since that decision was made, American stamps have come to include more and more kinds of people. Indeed, stamps provide a visual history of American thinking about gender and race in a widely disseminated and easily recognizable tiny form.

Heritage Images/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

A tradition codified

That tradition continued for both currency and stamps until 1866, when it became codified into law.

Why did depicting only the dead on U.S. currencies became a national priority in the year after the end of the Civil War? The answer emerged from congressional debate: Had living persons been allowed to appear on U.S. coins, stamps and banknotes, it would have been possible to depict U.S. citizens who would go on to become traitors to the nation.

This law has held fast, even as stamps have quickly evolved.

Heritage Images/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

At the end of the 19th century, different types of people began to appear on stamps as American democracy became more inclusive. At first, women were added: Queen Isabella of Spain in 1893 and Martha Washington in 1902. The portrait of a Native American, the Sioux chief Hollow Horn Bear, appeared in 1923. Then an African American, Booker T. Washington, in 1940. In the decades since, persons of other ethnicities and sexual orientations have been honored on stamps. For example, Hispanic labor leader Cesar Chavez appeared in 2003, Arab American diplomat Philip C. Habib in 2006 and gay rights activist Harvey Milk in 2014.

Massimo Vernicesole/iStock via Getty Images

In all these cases, history, not heredity, determined who appeared. The only figures guaranteed a stamp are presidents, who become eligible for this honor one year after their death. The idea remains, though, that unlike King Charles III, they did not ascend to the office of president, but earned it due to their contribution to the democratic ideals of the United States.

The politics of representation

Despite these clear ideals, the question of representation has dogged postal portraits. So it is no surprise that when the Post Office established the Citizen’s Stamp Advisory Committee in 1957 to make recommendations to the postmaster general about future designs for stamps, it decreed that its deliberations be kept secret.

Nonetheless, the current diversity of the cast of characters appearing on U.S. stamps continues to generate criticism. People with pronounced political views of whatever stripe can be unhappy with choices that seem to represent their opponents.

A different critique we develop in our book is that apolitical diversity allows the Postal Service to abdicate the responsibility of illustrating what democracy should look like. If you do not pick a side, we argue, then how can citizens know which behaviors or positions are undemocratic?

Heritage Images/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

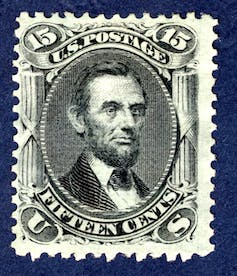

Indeed, the pitfalls of the good-people-on-both-sides approach was strikingly illustrated in a 1995 pane of 20 stamps commemorating the Civil War, which included both Abraham Lincoln, the president of the Union, and Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy. Surely the legislators who in 1866 decried the possibility of traitors being featured on federal currencies would be baffled by the choice of Davis.

Which raises a problem: If former President Donald Trump is convicted of violating national security laws and obstructing justice, which principle should prevail: that all presidents be guaranteed a postage stamp? Or that only those persons whom history judges to have been faithful to the nation and its democratic principles can appear on U.S. stamps, coins and bank notes?

It’s too soon to know the answer to these questions. But the controversy over who should represent the United States on stamps and what democracy looks like has been with our nation since 1792.

Leon Neal via Getty Images